Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Blackbeard's

Pirates in Williamsburg

A True Account of the Trials, Pardons,

and Executions

of the Crew of the World's Most Famous Pirate

by Guest Columnist Robert

Jacob

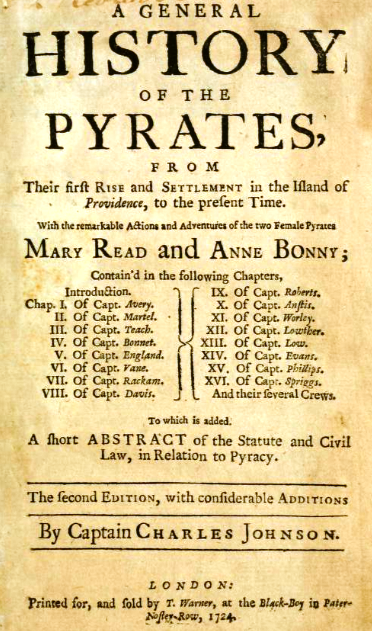

Charles Johnson’s 1724 Book

For 300 years, most historians and

authors of books on pirates have relied heavily on

one primary source, a book published in 1724 titled,

A General

History of the Pyrates from Their

first Rise and Settlement in the Island of

Providence, to the present Time. This book was

written by Captain Charles Johnson. They assumed

that since it was written in 1724, it must be

accurate and correct. But this is not the case.

Johnson, which was a pen name, was focused on

selling books, not telling the facts. Most of the

details described in Johnson’s work are highly

embellished or created by the author. These insights

place his book into the category of historical

fiction, especially when Johnson’s stories are

compared to known facts about Blackbeard. For 300 years, most historians and

authors of books on pirates have relied heavily on

one primary source, a book published in 1724 titled,

A General

History of the Pyrates from Their

first Rise and Settlement in the Island of

Providence, to the present Time. This book was

written by Captain Charles Johnson. They assumed

that since it was written in 1724, it must be

accurate and correct. But this is not the case.

Johnson, which was a pen name, was focused on

selling books, not telling the facts. Most of the

details described in Johnson’s work are highly

embellished or created by the author. These insights

place his book into the category of historical

fiction, especially when Johnson’s stories are

compared to known facts about Blackbeard.

In his 2004 publication, “Daniel Defoe, Nathaniel

Mist, and the General History of the Pyrates,” Arne

Bialuschewski, a professor at Trent University,

remarked that in

August

1724, only three months after the first edition

had appeared . . . a letter purportedly written

by a country correspondent . . . reported that

‘this shim-sham Story of Pyrates’ was

interpreted by one particular member of his club

as a mysterious political allegory rather than

contemporary history. (Bialuschewski, 35)

It took until the late

twentieth century for most historians to realize

this. As primary source documents became widely

available on the internet, historians began to

compare the verifiable facts against those in

Johnson’s book, and questioned its accuracy.

Professor Bialuschewski uncovered many fascinating

facts about this series of books as well as the

identity of the author, Charles

Johnson.

According to Bialuschewski, in 1932,

literary scholar John Robert Moore suggested that Daniel

Defoe might have been Charles Johnson, based

on a similarity in literary style. This concept

became widely circulated. Many recently republished

versions of this book identified Daniel Defoe as the

author and many modern libraries, including the

Library of Virginia and the State Library of North

Carolina, catalog this book under the author Daniel

Defoe. According to Bialuschewski, in 1932,

literary scholar John Robert Moore suggested that Daniel

Defoe might have been Charles Johnson, based

on a similarity in literary style. This concept

became widely circulated. Many recently republished

versions of this book identified Daniel Defoe as the

author and many modern libraries, including the

Library of Virginia and the State Library of North

Carolina, catalog this book under the author Daniel

Defoe.

After extensive research, Bialuschewski discovered

that the actual identity of Charles Johnson was

Nathaniel Mist, who began publishing a tabloid paper

titled The Weekly Journal; or, Saturday’s Post

on 15 December 1716. This was a politically oriented

publication that ran articles opposed to the Whig

party. Daniel Defoe was hired by Nathaniel Mist to

write for the paper. Beginning in December 1719,

fictional accounts of pirates began to regularly

appear in this publication. In 1724, Mist decided to

compile these stories into one book. The first

edition was registered with The

Stationer’s Company on 24 June 1724, for

Nathaniel Mist. The book title mentioned above is

the second edition, released in August 1724, just

three months after the first edition, and is the one

most widely circulated today.

Conclusive evidence suggests that the author of the

celebrated work was, in fact, Nathaniel Mist.

However, I shall continue to use his pen name,

Charles Johnson, throughout the rest of this paper.

Even though most of the details described in

Johnson’s work prove to be unfounded, some of them

are valid. This makes it maddening for researchers

who use Johnson’s book as a source. Which facts can

be relied upon and which facts should be completely

discounted? The solution is to cross-reference

everything with other primary sources.

Fortunately,

when it comes to Blackbeard, many primary sources

are available.1 These

include numerous letters mentioning Blackbeard

written by Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor, Alexander

Spotswood. They also include letters written

by Captain Ellis Brand, the Royal Navy officer and

area commander responsible for the operation against

Blackbeard, and Lieutenant

Robert Maynard, the officer who led the attack

on Blackbeard’s sloop. The

Boston News-Letter also provides a great

deal of information, although one must remember that

newspapers often make errors in writing their

stories. Logbooks from various naval vessels, as

well as the minutes from meetings of the Councils of

both Virginia and North Carolina, provide valuable

information in checking Johnson’s details. But the

most useful resources in getting to the truth are

several financial documents written by Anthony

Cracherode, the Treasury Solicitor for Great

Britain. Fortunately,

when it comes to Blackbeard, many primary sources

are available.1 These

include numerous letters mentioning Blackbeard

written by Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor, Alexander

Spotswood. They also include letters written

by Captain Ellis Brand, the Royal Navy officer and

area commander responsible for the operation against

Blackbeard, and Lieutenant

Robert Maynard, the officer who led the attack

on Blackbeard’s sloop. The

Boston News-Letter also provides a great

deal of information, although one must remember that

newspapers often make errors in writing their

stories. Logbooks from various naval vessels, as

well as the minutes from meetings of the Councils of

both Virginia and North Carolina, provide valuable

information in checking Johnson’s details. But the

most useful resources in getting to the truth are

several financial documents written by Anthony

Cracherode, the Treasury Solicitor for Great

Britain.

Throughout this paper, I shall discuss each of the

details surrounding the death, capture, and

imprisonment of Blackbeard’s crewmen, and primary

source documents. Before I begin with Blackbeard’s

crew, I must briefly dispel some of the most popular

stories about Blackbeard, as told by Johnson.

Blackbeard’s battle with HMS Scarborough

never happened. Johnson wrote:

A few Days

after, Teach fell in with the Scarborough Man

of War, of 30 Guns, who engaged him for some

Hours; but she finding the Pyrate well mann’d,

and having tried her strength, gave over the

Engagement . . . . (Johnson, 71)

Historians have examined

HMS Scarborough’s logbook and there is no

mention of such a battle. A look at the list of

ship’s stations published in the 16 to 23 December

1717 edition of The Boston News-Letter

reveals that HMS Scarborough was stationed

at Barbados, not Nevis as Johnson claims.

Blackbeard’s fourteen wives cannot be verified

either. Although this is among the most popular of

Johnson’s Blackbeard tales, there are no

contemporary records or even comments about any wife

except a casual comment made by Captain Brand who

wrote:

he

design’d to be an inhabitant & leave of his

Piraticall Life and the sword to put a life so

to his designs he marryed there. (Brand, 6

February)

The wounding of Israel

Hands is most likely another creation of

Johnson.

One Night

drinking in his Cabin with Hands, the

Pilot, and another Man; Black-beard

without any Provocation privately draws out a

small Pair of Pistols, and cocks them under the

Table, which being perceived by the Man, he

withdrew and went upon Deck, leaving Hands,

the Pilot, and the Captain together. When the

Pistols were ready, he blew out the Candle, and

crossing his Hands, discharged them at his

Company, Hands, the Master, was shot

thro’ the Knee and lam’d for life . . . .

(Johnson, 86)

There is no contemporary

account that corroborates this story. As will be

detailed later, Hands testified for the prosecution

in the March 1719 trial against four of Blackbeard’s

crew. In September of 1718, Blackbeard

allegedly assaulted a North Carolina resident named

William Bell, and the four pirates charged were

simply present. Hands was not present but testified

that he was informed of the incident when Blackbeard

and the others returned to Ocracoke.

Most of his testimony was directly against

Blackbeard. If this horrific wounding did indeed

occur, it seems unlikely that Hands would have

failed to mention anything about it in his testimony

against Blackbeard.

Johnson’s details of the battle at

Ocracoke are filled with many inaccuracies

when compared to the accounts of Lieutenant Robert

Maynard, the officer who led the naval force that

attacked Blackbeard, and Captain Ellis Brand, the

overall commander.

Capture of the Pirate,

Blackbeard by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris,

1920

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

Finally, Johnson’s version of a man whom many

believed to be Black

Caesar, who was posted below deck with a match

and orders to blow up the Adventure, is

embellished not only by Johnson but also by

subsequent historians. The origin of this account

comes from a letter from Spotswood to the

Commissioners for Trade and Plantations.

His orders

were to blow up his own vessell if he should

happen to be overcome, and a Negro was ready to

set fire to the Powder had he not been luckily

prevented by a Planter forced on board the night

before & who lay in the Hold of the sloop

during the actions of the Pyrats.

(Spotswood)

Johnson recounts this

incident as:

. . . for

before that Teach had little or no Hopes of

escaping, and therefore had posted a resolute

Fellow, a Negroe, whom he had bred up, with a

lighted Match, in the Powder-Room, with Commands

to blow up when he should give him Orders, which

was as soon as the Lieutenant and his Men could

have entered, that so he might have destroy’d

his Conquerors . . . . (Johnson, 85)

Johnson’s embellishment

is the comment that he was “a Negroe whom he had

bred up.” That comment seems to be a matter of

poetic license. Johnson doesn’t give any name for

this individual anywhere in the text, so just going

on Johnson’s book, the man with the match could have

been any of the surviving pirates.

The name of “Black Caesar” seems to be the invention

of other authors retelling Johnson’s account in the

twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Johnson never

wrote “Black Caesar” anywhere in his book. He did

correctly name one of the captive pirates as Caesar,

but the word “Black” was never associated with that

name. Other than mentioning that this unnamed

individual was “a Negroe,” Johnson did not specify

the race of any of Blackbeard’s pirates, nor did he

include any substantive information to indicate

which of Blackbeard’s crewmen were black. Modern

historians can accurately identify the race of these

pirates, at least the captured ones, by piecing

together clues found in letters written by both

Brand and Spotswood.

It seems logical that twentieth-century authors

searching to assign a name to the “Negro. . . ready

to set fire to the Powder,” mentioned by Spotswood

in his letter, chose the only name on Johnson’s list

that did not include a Christian name. Perhaps there

are others, but the earliest reference that I have

found that identifies this individual as Caesar is

Hugh F. Rankin’s The Pirates of Colonial North

Carolina published in 1960. The name Black

Caesar as the pirate with the match doesn’t appear

in print until 2006 in Angus Konstam’s Black

Beard.

As for Blackbeard’s crew held in Williamsburg,

Virginia, it is best to begin with the first of

Blackbeard’s pirates to be arrested, his former

quartermaster William

Howard.

William Howard

William Howard had been with Blackbeard since the

beginning. There were numerous references

identifying Howard as Blackbeard’s quartermaster

between 1716 and 1718, including one made by

Spotswood after his arrest. Howard was visiting

Kecoughtan (Hampton, Virginia), when Spotswood

ordered a justice of the peace to arrest him and

seize the £50 he was carrying, as well as his two

slaves. In a letter from 22 December 1718, Spotswood

described Howard as “insolent,” with “no lawful

business” and a “Vagrant seaman.”

. . .

Howard, Tach’s Quarter Master came into this

Colony with two Negros which he own’d to have

been Piratically taken, the one from a French

ship and the other from an English Brigantine[.]

I caused them to be seized [pursuant] to His

Majestys Instructions, upon which encouraged by

the countenance he found here, he commenced a

suit against the officers who made the seizure,

and his insolence became so intolerable without

applying himself to any lawful business that the

justice of the Peace where he resided thought

fitt to send him on board one of the Kings ships

as a Vagrant seaman. (Spotswood)

Howard was imprisoned on

board Captain Brand’s ship Pearl until 30

October 1718, and then transferred to the gaol in

Williamsburg. It wasn’t long before he was

joined by three other pirates, who were not members

of Blackbeard’s crew: Henry Man, William Stoke, and

Adult Van Pelt were arrested at Kecoughtan on 28

November 1718, and held on the Pearl until 19

December 1718, when they were brought to

Williamsburg.2

. . . that

the Sd. four pyrates were taken and

delivered to Justice by the said Capt.

Gordon . . . hath by his annexed Affidavit of

the 25th. of February last made Oath,

that Wm. Howard . . . was taken up at

Kiquotan in Virginia the 16th. of

Septer. 1718, and putt on board the Pearl Man of Warr, in which

Ship he remained a Prisoner untill the 30th.

of Oct. 1718, at which time he was sent up in

Irons to Williamsburgh to be tryed for Pyracy

and was accordingly convicted, and condemn’d to

be Hang’d, and that Henry Man, Wm.

Stoke & Adult Van Pelt. (the three other

pyrates named in the said Certificate) were

taken up near Kiquoatan aforesd. the

28th of Nov. 1718, and brot.

on Board his Maty’s Sd. Ship the

Pearl, as Pyrates, where they remained prisoners

until the 15th. Of Dec. following,

when they were Sent up to Williamsburgh in

Irons.

| For

the Sd. Wm. Howard a common Sailor |

20"

|

0" |

0 |

| For the Sd. Henry Man Ditto |

20" |

0" |

0 |

| For the Sd. Wm. Stoke |

20" |

0" |

0 |

| For the Sd. Adult Van Pelt |

20" |

0" |

0 |

|

80" |

0" |

0 |

Howard was charged on

five counts.4 His

trial was held in Williamsburg on 6 November 1718,

as mentioned in Spotswood’s letter dated 7 November

1718.

The

evidence given in yesterday upon the Tryall of

his Quarter Master William Howard, who now lyes

here under the Sentence of death, for being

clearly convicted of manifest Pyracys since the

fifth of January last, and even of one committed

but two days before their running aground at

Top-sail-Inlet at which time they Robbed an

English Brigantine comeing from Guinea and the

Negroes they took out of her are well known to

be in your Province (“Spotswood Letter”)

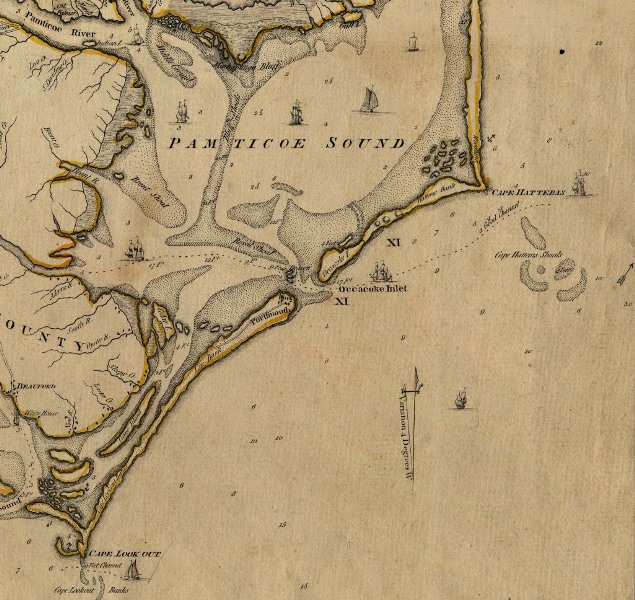

Vessels of the Engagement

There were two Royal Navy

ships stationed in Kecoughtan. The largest

ship was HMS Pearl,

a fifth-rate ship of forty guns under the command of

Captain George Gordon. The second ship was HMS Lyme,

a sixth-rate

ship of twenty guns under the command of

Captain Ellis Brand.

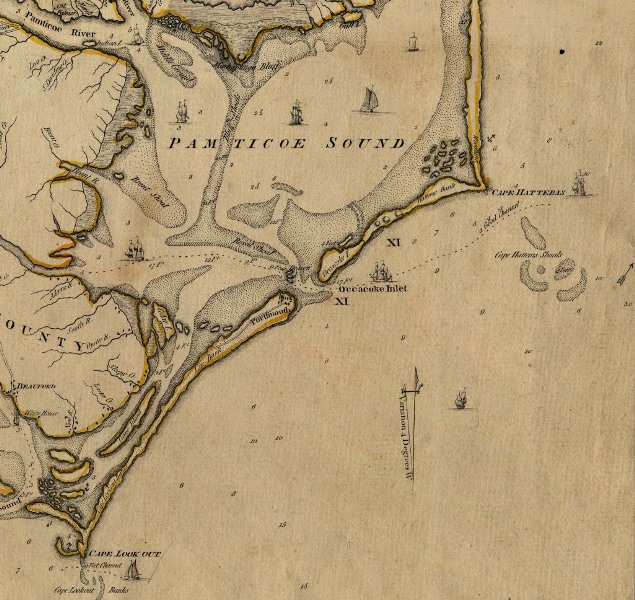

For the engagement against Blackbeard at Ocracoke,

Spotswood realized that these large ships would be

ineffective in the relatively shallow waters of

Pamlico Sound, so he purchased two sloops for the

operation and hired two pilots from North Carolina

to help with navigation. In a letter written on 22

December 1718, Spotswood wrote:

Having

gained sufficient Intelligence of the Strength

of Tache’s Crew, and sent for Pylots from

Carolina . . . It was found impracticable for

the Men of war to go into the shallow and

difficult Channells of that Country . . .

Accordingly I hyred two sloops and put Pilots on

board, and the Captains of his Majestys Ships

having put 55 Men on board under the command of

the first Lieutenant of the Pearle &

an officer from the Lyme . . . .

(Spotswood)

The names of those two sloops, Jane and Ranger,

can be found in the logbook of the Lyme:

. . .

saild the Ranger & Jane sloops

with 22 of our men & 32 of Pearle in quest

of ye Pirate Teech in N Caroline. (Lyme)

Lieutenant

Robert Maynard was on board Jane and

in command of the operation at Ocracoke. Midshipman

Hyde commanded the Ranger. On 17 December

1718, Maynard wrote a letter to his friend,

Lieutenant Symonds of HMS Phoenix,

in which he mentioned that his two sloops had “no

Guns, but only small Arms and Pistols.” Maynard also

mentioned that Blackbeard’s sloop “had on Board 21

Men, and nine Guns mounted.” (Cooke, 306) Lieutenant

Robert Maynard was on board Jane and

in command of the operation at Ocracoke. Midshipman

Hyde commanded the Ranger. On 17 December

1718, Maynard wrote a letter to his friend,

Lieutenant Symonds of HMS Phoenix,

in which he mentioned that his two sloops had “no

Guns, but only small Arms and Pistols.” Maynard also

mentioned that Blackbeard’s sloop “had on Board 21

Men, and nine Guns mounted.” (Cooke, 306)

The validity of Lieutenant Maynard’s letter has

fallen into question by some historians. The only

known source of the actual

letter comes from the 25 April 1719 edition of

The Weekly Journal, or Saturday’s Post, the

tabloid magazine published by Nathaniel Mist, also

known as Charles Johnson. In that magazine,

Maynard’s letter was supposedly reproduced exactly

as it originally appeared. However, because

Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates

has been proven to have many inaccuracies,

exaggerations, and fictionalized accounts, Maynard’s

letter has been categorized as a possible invention

on the part of Mist. An article printed in the

Monday, 23 February to Monday, 2 March 1719 issue of

The Boston News-Letter sheds light on this

question. When comparing Maynard’s letter with the

article, it becomes clear that Maynard’s letter must

have been the newspaper’s primary source. All the

details align, such as the Adventure having

nine guns, and that Maynard shot away his fore

halyards and put him ashore. Even some of the

specific phrases, such as “dismal cuts,” are

identical.

These facts only appear in Maynard’s letter, not in

Brand’s report. Additionally, The Boston

News-Letter article even states that they

received this information in a letter from North

Carolina. This makes sense. Maynard’s letter was

sent to his friend Lieutenant Symonds, who was an

officer aboard HMS Phoenix stationed at

New York Harbor. Maynard’s letter was reprinted in

Arthur Cooke’s 1953 article, “British Newspaper

Accounts of Blackbeard’s Death,” published in The

Virginia Magazine of History and Biography.

Blackbeard’s sloop was named Adventure, as

identified in the records of the Williamsburg trial,

which was included in the Minutes of the North

Carolina Governor’s Council:

Hesikia

Hands late Master of the Sloop Adventure Commanded

by Edward Thache. (Minutes)

Summary of Vessels

Vessel

|

Commander

|

Location

|

HMS

Pearl

|

Captain

George Gordon

|

Kecoughtan

|

HMS

Lyme

|

Captain

Ellis Brand

|

Kecoughtan

|

Sloop

Jane

|

Lieutenant

Robert Maynard

|

Battle

at Ocracoke

|

Sloop

Ranger

|

Midshipman

Hyde

|

Battle at Ocracoke

|

| Sloop

Adventure |

Blackbeard

|

Battle

at Ocracoke

|

Battle Statistics

Details of the battle are documented in two letters

and contradict the account in Charles Johnson’s A

General History of the Pyrates. The first

letter was the letter mentioned above, the one from

Lieutenant Maynard to Lieutenant Symonds. The other

letter was written by the area commander, Captain

Ellis Brand of Lyme to the Secretary of Admiralty

and dated 6 February 1719.

Maynard gives the number of men at the start of the

battle as:

Jane (Maynard’s

Sloop) – 32 men

Ranger (Hyde’s

Sloop) – 22 men

Adventure (Blackbeard’s

Sloop) – 21 men

Brand gives the number

of men at the start of the battle as:

Jane –

Lieutenant Maynard and 35 men

Ranger –

Midshipman and 25 men and pilot from North

Carolina

Adventure –

19 men, 13 white / 6 black

Maynard’s list of

casualties and prisoners:

Jane –

8 killed and 18 wounded

Ranger – Hyde

killed and 5 men wounded

Adventure –

12 killed, including Blackbeard

Pirates taken prisoner

at Ocracoke – 9, mostly black (all wounded)

In Maynard’s original

letter, he wrote “12 besides Blackbeard,” however,

these numbers do not add up. Most historians agree

that Maynard meant to say “12, including

Blackbeard.” According to Brand’s letter, he had

traveled to Bath, North Carolina on horseback while

Maynard and Hyde took the sloops to find Blackbeard.

While in Bath, he arrested six of Blackbeard’s

pirates who weren’t at Ocracoke. After the battle,

he sent word for the sloops to join him at Bath.

Brand’s list of casualties and prisoners were:

Jane –

9 died

Ranger –

Commander and Coxon killed, William Baker wounded

Total both Royal Navy

sloops – more than 20 wounded

Adventure –

10 white men killed

Pirates taken prisoner

at Ocracoke – 3 white and 6 black (all wounded)

Pirates taken prisoner

(by Brand) on shore at Bath – 6

List of Pirates

Maynard lists twelve killed while Brand lists ten.

It is possible that two of the pirates were

unidentified by name. Maynard included them in the

body count, but Brand omitted them. Both Maynard and

Brand list nine pirates captured after the battle.

However, they differ on the total pirates killed.

Johnson provided the following list of pirates

killed and captured on page 90 of A General

History of the Pyrates.

The

Names of the Pyrates killed in the Engagement

are as follow.

Edward Teach, Commander.

Philip Morton, Gunner.

Garrat Gibbens, Boatswain.

Owen Roberts, Carpenter.

Thomas Miller, Quarter-Master.

John Husk,

Joseph Curtice,

Joseph Brooks, (1)

Nath. Jackson.

All the

rest, except the two last, were wounded and

afterward hanged in Virginia.

| John

Carnes, |

Joseph

Philips, |

| Joseph

Brooks, (2) |

James

Robbins, |

James

Blake,

|

John

Martin, |

| John

Gills, |

Edward

Salter, |

| Thomas

Gates, |

Stephen

Daniel, |

| James

White, |

Richard

Greensail. |

| Richard

Stiles, |

Israel

Hands, pardoned. |

| Caesar, |

Samuel

Odel, acquited. |

Other historians have

stated that Johnson got his information from a list

of captured and killed that was sent to the

Admiralty. I have not been able to find that list in

a primary source. There are two glaring errors in

Johnson’s “captured” list. The first of these errors

is that Johnson says they were all wounded. The ones

arrested in Bath would certainly not have been

wounded. Second, Johnson’s “captured” list contains

sixteen names. This contradicts Johnson’s text where

he writes that fifteen pirates were captured.

[T]he Lieutenant sailed back to

the Men of War in James River, in Virginia,

with Black-beard’s Head still hanging at

the Bolt-sprit End, and fiveteen Prisoners,

thirteen of whom were hanged. (Johnson, 86) [T]he Lieutenant sailed back to

the Men of War in James River, in Virginia,

with Black-beard’s Head still hanging at

the Bolt-sprit End, and fiveteen Prisoners,

thirteen of whom were hanged. (Johnson, 86)

This fifteen-count total

appears to be correct and agrees with Lieutenant

Maynard’s report.

Once again, the Cracherode report gives us better

information. Notice that payment was made for the

pirates who were brought in alive, but no payment

was made for those who were dead, including

Blackbeard (apparently bringing his head in wasn’t

enough). In order to qualify for the payment, the

pirate must have been tried and convicted.

. . . in

respect of the 8 Pyrates taken in the said

Engagement with Thach on the 22th.

of Novm. 1718, and of

the other 5 pyrates taken on Shoar (which by the

annexed Affidavit of Tho: Tucker appear to have

been taken near Bath Towne in North Carolina,

after the said Engagement was over) . . .

|

£. |

S. |

d. |

Hezekiah Hands

Master (as appears by the

Sd Lieutent

Govern.'s Certificate) |

40. |

0. |

0. |

| John Carnes |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| Joseph Brookes

Jun |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| James Blake |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| John Giles |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| Thomas Gates |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| James White |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| Richd. Stiles |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| John Martyn |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| Edwd.

Salter |

20. |

0. |

0. |

Steph: Daniel

|

20. |

0. |

0. |

| Richd.

Greensail |

20. |

0. |

0. |

| Cesar |

20. |

0. |

0. |

|

280. |

0. |

0. |

Which said

sume of 280£ I am most humbly of

Opinion ought to be divided between the Sd.Captains

Gordon, and Brand, and the Officers & other

persons concerned with them in the said

Engagement and Captures according to the

Proportions herein before Specifyed.

But as to the

said 2 Captains further Claime by Virtue of the

said Certificate of Rewards in respect of the

pyrates hereafter named Viz.

Edwd.

Thach Capt.

Philip Morton

Gunner

Garrot Gibbons

Boatswain

Owen Roberts

Carpenter

John Philips

Sailmaker

John Husk

Joseph Curtis

Joseph Brookes

Tho: Miller

&

Nath: Jackson

I am most humbly of

Opinion, that in regard all the said last named

persons appear by the said Certificate to have

been killed in the said Engagement, and not to

have been taken and convicted of Pyracy, no

Reward is due in Respect of them, or any of

them, by the words of his Majestys said

proclamation.5

(Cracherode, 139-140)

Here is a comparison of

the lists of those killed.

| Johnson’s List |

Cracherode’s List |

| Edward

Teach (Commander) |

Edwd.

Thach Capt. |

| Philip

Morton (Gunner) |

Philip

Morton Gunner |

| Garret

Gibbons (Boatswain) |

Garrot

Gibbons Boatswain |

| Owen

Roberts (Carpenter) |

Owen

Roberts Carpenter |

| Thomas

Miller (Quarter-Master) |

Tho:

Miller |

| John

Husk |

John

Husk |

| Joseph

Curtice |

Joseph

Curtice |

| Joseph

Brooks (1) |

Joseph Brookes |

| Nathaniel

Jackson |

Nath:

Jackson |

|

John

Philips Sailmaker |

|

|

| Total: 9 |

Total: 10 |

Note that Joseph Phillips on Johnson’s “captured”

list appears on Cracherode’s “killed” list as John

Philips. Johnson obviously makes an error in placing

him on the “captured” list. Adding his name to the

“killed list” makes a total of ten killed and agrees

with Brand’s report. This is also in agreement with

Johnson’s own book where he says “fiveteen

Prisoners” just four pages earlier. The other

discrepancy is with his first name. So far, no

additional evidence has been found to tell us if his

name was Joseph or John.

Comparing the Cracherode report to Brand’s letter,

one immediately notices several inconsistencies.

Brand states that nine men were taken at Ocracoke

and six in Bath for a total of fifteen, while

Cracherode’s report mentions eight pirates captured

at Ocracoke and five captured at Bath, for a total

of thirteen. Captain Ellis Brand’s 6 February 1719

letter reads, “Pyrate had nineteen men, Thirteen

White and Six negroes, ten white men kill’d and the

rest of the Prisoners were all wounded . . . I took

six of them from the shoar.” (Brand, 6 February)

Cracherode’s Report on Petitions reads, “. .

. in respect of the Eight Pyrates taken in the said

Engagemt. with Thatch on the 22d. of Nove. 1718. And

of the five other pyrates taken on shoar.”

(Cracherode, 139)

Here is a comparison list, with Joseph Phillips on

the list of those killed.

Johnson’s List

|

Cracherode’s List |

| John

Carnes |

John

Carnes |

| Joseph

Brooks (2) |

Joseph

Brookes Jun |

| James

Blake |

James

Blake |

| John

Giles |

John

Giles |

| Thomas

Gates |

Thomas

Gates |

| James

White |

James

White |

| Richard

Stiles |

Richd.

Stiles |

| Caesar

|

Caesar

|

| James

Robbins |

(Not

listed) |

| John

Martin |

Jno

Martyn |

Edward

Salter

|

Edwd. Salter |

| Stephen

Daniel |

Steph:

Daniel |

| Richard

Greensail |

Richd.

Greensail |

| Israel

Hands, pardoned |

Hezekiah

Hands, Master |

| Samuel

Odell, acquitted |

(Not

listed) |

I shall address the difference in the numbers taken

at Bath later. I will first delve into the

discrepancy in the totals, fifteen versus thirteen.

The two names on Johnson’s original list that are

missing from Cracherode’s are Samuel Odell and James

Robbins.

Samuel Odell and James Robbins

The fact that Samuel Odell and James Robbins are

missing from Cracherode’s list can be explained

after considering two sources.

Spotswood’s letter to the Commissioners for Trade

and Plantations includes:

His orders

were to blow up his own vessell if he should

happen to be overcome, and a Negro was ready to

set fire to the Powder had he not been luckily

prevented by a Planter forced on board the night

before & who lay in the Hold of the sloop

during the actions of the Pyrats.

(Spotswood)

Charles Johnson recounts

this incident as:

. . . for

before that, Teach had little or no

Hopes of escaping, and therefore had posted a

resolute Fellow, a Negroe, whom he had bred up,

with a lighted Match, in the Powder-Room, with

Commands to blow up, when he should give him

Orders, which was as soon as the Lieutenant and

his Men could have entered, that so he might

have destroy’d his Conquerors: and when the

Negro found how it went with Black-beard,

he could hardly be perswaded from the rash

Action, by two Prisoners that were then in the

Hold of the Sloop. (Johnson, 85)

Spotswood mentions one

prisoner, a “Planter,” and Johnson mentions two

prisoners. These two could only have been Samuel

Odell and James Robbins.

Samuel Odell. There is no reference to

Samuel Odell in Spotswood’s letter or in

Cracherode’s report. The only source mentioning

Samuel Odell is Charles Johnson’s A General

History of the Pyrates when he wrote:

Samuel Odell,

was taken out of the trading Sloop, but the

Night before the Engagement. This poor Fellow

was a little unlucky at his first entering upon

his new Trade… (Johnson, 86)

Johnson most likely saw

an original report, since the names of the other

pirates listed were accurate. Therefore, Johnson was

probably correct when he said Samuel Odell was

“acquitted.” (This is one of the few facts that

Johnson got right!) If proven Odell wasn’t a pirate,

he would be released and would not appear on

Cracherode’s list.

Many modern authors recognize Samuel Odell as the

man who prevented the destruction of the Adventure,

but Johnson identified Odell as the master of a

trading sloop. Spotswood clearly described this man

as a “Planter.” If it wasn’t Odell, who was it? The

only other person not on Cracherode’s list was James

Robbins.

James Robbins. There is very strong evidence

that James Robbins was the “Planter” Spotswood

referred to in the letter. Allen Norris published a

book containing a transcript of all the land deeds

in Bath between 1696 and 1729. This book holds the

answers to several of Blackbeard’s crewmen.

A deed transcribed in Norris’s book named James

Robbins as the man who purchased lot #13 on 9

September 1718, from John Lillington, who had

purchased the property from Governor Charles Eden

just five months before. In late 1718, James Robbins

owned Eden’s 400-acre property, including Eden’s

large house.

The property next to Robbins’s land belonged to Tobias Knight, who

bought the property from Robert Daniel in 1716.

Knight was, of course, the Secretary General, Chief

Justice, and Customs Inspector of North Carolina. He

was also the author of the letter dated 17 November

1718, that was found by Maynard on board Adventure

after the battle at Ocracoke. This letter played

a vital role in the charges against Tobias Knight

for his involvement with Blackbeard and was

transcribed in the minutes of the governor’s

council, which met on 27 May 1719.

Blackbeard obviously had this letter in his

possession before 21 November 1718, as he was killed

on the morning of the 22nd and the letter was found

on his sloop. How did he get this letter in just

three days? The only answer was that James Robbins,

Tobias Knight’s neighbor, brought it to him.

There is conclusive evidence that James Robbins must

have been acquitted. He was not listed in the

Cracherode report, and therefore, was most likely

the man identified by Spotswood as the “Planter

forced on board the night before.” But most

importantly, there were several deeds recorded in

Bath naming James Robbins after 1718. He witnessed a

deed in 1721 and another deed showed that James

Robbins sold all 400 acres of his property to Robert

Campaine for £445 on 9 July 1724.

Specifying the Location of Capture and

Identifying their Race

Contemporary reports mention that the pirates were

captured in either Ocracoke

or Bath,

but they do not indicate the names of the pirates

taken at the specific locations, nor do they

identify the race of the individuals captured.

However, as described later in this paper, both are

important in helping to solve the mystery of

precisely what occurred in Williamsburg.

The discrepancy between the Brand letter and the

Cracherode report as to the number captured in Bath

can be easily explained by a simple error. Brand

lists six while Cracherode lists five. Brand

personally arrested those in Bath and should know

the count. As the total numbers all add up between

the two reports, it seems likely that an error

occurred, and that one of those taken in Bath was

accidentally added to the Ocracoke list by the time

Cracherode received it.

As for the discrepancy in the number of Africans

taken, Brand mentions six Negroes, while Spotswood

lists only five. Once again, I shall refer to

Captain Ellis Brand’s letter, “Account of taking

Blackbeard,” 6 February 1719, which reads:

The Pyrate

had nineteen men, Thirteen White and Six negroes

. . .

Spotswood’s address to

the Council of Colonial Virginia in March of 1719

reads:

The

Governor acquainted the Council, that five

Negroes of the crew of Edward Thack & taken

on board his Sloop remaine in Prison for Pyracy.

(Executive, 495-496)

This discrepancy can

easily be explained if one assumes that Brand simply

made a mistake in his identification of one of the

captives. Brand wasn’t at the battle of Ocracoke and

may not have ever seen any of those who were

captured there. Weeks after the battle, Maynard

sailed the sloop containing the captured pirates to

Bath, but they would have been imprisoned below

deck. In any event, as the total numbers of all the

pirates captured add up nicely, there isn’t anyone

missing.

The five pirates of African descent can easily be

identified. Four of their names appear in the

Minutes of the North Carolina Governor’s Council for

27 May 1719.

Evidences

called by the Names of James Blake, Richard

Stiles, James White, and Thomas Gates were

actually no other than foure Negroe Slaves.

I shall discuss the

reasons for their names being read into the minutes

in greater detail later in this paper.

As for the fifth pirate of African descent, his

identity can be ascertained by the process of

elimination. He is the man named Caesar, the only

man without a last name.

The following list specifies which captives were of

African descent and gives the most likely location

of their capture. According to author and researcher

Kevin

Duffus, author of The Last Days of Black

Beard the Pirate, the ones listed as taken in

Bath are based upon documented activity in that town

just prior to the battle.

Johnson's List

|

Cracherode's List

|

Capture at

Ocracoke

|

Captured at

Bath

|

John

Carnes

|

John

Carnes

|

X

|

|

Joseph

Brooks (2)

|

Joseph

Brooks, Junr

|

|

X

|

James

Blake

|

James

Blake (African)

|

X

|

|

John

Giles

|

John

Giles

|

|

X

|

Thomas

Gates

|

Thomas

Gates (African)

|

X

|

|

James

White

|

James

White (African)

|

X

|

|

Richard

Stiles

|

Richd.

Stiles (African)

|

X

|

|

Caesar

|

Caesar

(African)

|

X

|

|

John

Martin

|

John

Martyn

|

|

X

|

Edward

Salter

|

Edwd.

Salter

|

|

X

|

Stephen

Daniel

|

Steph:

Daniel

|

|

X

|

Richard

Greensail

|

Richd.

Greensail

|

X

|

|

Israel

Hands (Pardoned)

|

Hezekiah

Hands, Master

|

|

X

|

|

|

Total: 7

|

Total: 6

|

Taken at Ocracoke

Now we are down to fourteen of Blackbeard’s crew.

The thirteen listed in Cracherode’s report plus

William Howard. I will discuss those taken at

Ocracoke first.

Maynard returned to Kecoughtan on Saturday, 3

January 1719, aboard Blackbeard’s captured sloop

with his prisoners on board. The logbook of HMS Pearl

for that date reads:

This day

the Sloop Adventure Edward Thach formerly Master

(a Pyrat) anchor’d here from No.

Carolina comanded by my first Lieut.

Mr. Robt. Maynard who had

Taken the aforesaid Sloop, & destroy’d the

said Edward Thach & most of his men; he also

brought Thach’s head, hanging under his bowsprit

in order to present it to the Colony of

Virginia; he saluted me with 9 guns, I return’d

the like number . . . . (Duffus, 169)

Captain Gordon, Maynard’s

commanding officer and captain of the Pearl,

would have ordered all the prisoners to be

transferred to the ship and held for a short time

prior to being sent to Williamsburg, just as he had

done a few months earlier with William

Howard, Henry Mann, William Stoke, and Adult

Van Pelt.

Once in Williamsburg, there was an apparent issue

that Spotswood felt compelled to address in a letter

to his council.

The

Governor acquainted the Council, that he had

Delayed [five Negroes’] Tryal till the Severity

of the Winter Weather was over, that he might

have a full Council, in order that he might have

a more Solemn examination of the several piracys

of which these and the rest of that Crew have

been guilty . . . whither there be any thing in

the circumstances of these Negroes to exempt

them from under going the same tryall of other

Pirates. Whereupon the Council are of Opinion

that the said Negroes being taken on board a

Pirate Vessel, and by what yet appears, equally

concerned with the rest of the Crew in the same

Acts of Piracy, and ought to be tryed in the

same manner, and if any diversity appears in

their circumstances the same may be considered

on their Tryal. (Executive, 495-496)

Those “five Negroes” were

problematic from a legal standpoint. If they were

slaves, they wouldn’t be responsible for their

actions, as a slave had no choice when following

orders from their owners. Spotswood would have

spoken to Captain Gordon about his concerns and the

prisoners would have been separated from the others,

at least in terms of their treatment. The ones who

were peacefully taken in Bath might have been

treated differently, too. They weren’t directly

responsible for the deaths of any of Gordon’s men.

That left

two white men who were combatants and participated

in the action against Gordon’s men, Richard

Greensail and John Carnes. A logbook entry from HMS

Pearl dated 28 January 1719, might reveal

their fates. Captain Gordon wrote: That left

two white men who were combatants and participated

in the action against Gordon’s men, Richard

Greensail and John Carnes. A logbook entry from HMS

Pearl dated 28 January 1719, might reveal

their fates. Captain Gordon wrote:

Yesterday

in the afternoon the longboat came…This morning

sent 2 condemned pyrats ashore to Hampton to be

executed, which about 1/2 past 11 was done

accordingly. (Duffus, 174)

There is no direct

evidence that the two pirates Gordon executed were

indeed Richard Greensail and John Carnes, but the

idea is most compelling. Captain Gordon had the

authority to convene an Admiralty court on board his

ship and to carry out the sentence. He would have

wanted to proceed as quickly as possible and not

wait for a court in Williamsburg that might turn

them free on a technicality. Additionally, Gordon

would have wanted his crew to see the execution of

those responsible for the killing of their mates.

The standard means of execution for pirates was

hanging.

Extension of the King’s Proclamation

On

21 December 1718, King George extended his

proclamation. The following is an excerpt of the

proclamation. On

21 December 1718, King George extended his

proclamation. The following is an excerpt of the

proclamation.

We have

thought fit, by and with the Advice of Our

Privy-Council, to Issue this Our Royal

Proclamation; And We do hereby Promise and

Declare, That in case any the said Pirates

shall, on or before the First Day of July, in

the Year of Our Lord One thousand seven hundred

and nineteen, Surrender him or themselves to One

of Our Principal Secretaries of State in Great

Britain or Ireland, or to any Governor or

Deputy-Governor of any of Our Plantations or

Dominions beyond the Seas, every such Pirate and

Pirates, so Surrendering him or themselves, as

aforesaid, shall have Our Gracious Pardon of and

for such his or their Piracy or Piracies . . . .

(British, 179)

Of course, the entire proclamation is much longer,

but this passage is the important one. Unlike the

original proclamation, which had a cutoff date of 5

January 1718, after which any acts of piracy would

render the person ineligible, this new one didn’t

mention any such date. Everyone was eligible for the

pardon as long as they asked for it before 1 July

1719. Now, all of Blackbeard’s pirates held in

Williamsburg were eligible for a pardon.

William Howard’s Pardon

There is no question that William Howard was freed.

Captain Brand wrote that he

was found

guilty and received sentence of Death

Accordingly and his life is only owing to the

ships arrival that had his Majesties pardon on

board, the Night before he was to have been

executed. (Brand, 14 July)

And Spotswood wrote:

I received

some days ago the Honor of your Lordships of the

– of August and his Majestys Commission for

pardoning Pyrates which came very seasonably to

save Howard their Quartermaster then under

sentence of Death, but by his Majestys extending

his Mercy for all Piracys committed before the

18th of August, is now set at liberty.

. . . what I am

therefore in doubt of is, whether by the

remitting all forfeitures, His Majesty intends

only to restore the Pyrates to the Estates they

had before the committing their Pyracies, or to

grant them a Property also in the Effects which

they have Piratically taken. There is besides

the two Negro Boys about £50 in money and other

things taken from the aforementioned Howard,

& now in the hands of the Officer who seized

it on His Majestys behalf, of which an inventory

is lodged in the Secretarys office here. I

therefore pray your Lordships advice &

commands how these Effects are to be dispersed,

where the person for whose possession they were

found is pardoned. (Spotswood)

It is interesting to note

that Howard purchased Ocracoke Island in 1759 and

died there in 1794, at the age of 108.

At least two of the pirates taken in Kecoughtan were

also granted the king’s pardon. They were William

Stokes and Adult Van Pelt.

It is the

unanimous opinion of this Board that the said

Stokes and Van Pelt are fitt objects of his

Majesties mercy. (Executive, 497)

4 of the 5 “Negroes” Stand Trial

An incident occurred in Bath on 14 September 1718,

near Tobias Knight’s house. Late that night, William

Bell was traveling by periauger on the Pamlico River

when he was attacked by several men in another

periauger.6 The

next morning, Bell stated that he believed he was

attacked by

one Thomas

Unday and one Richard Snelling commonly called

Titery Dick to be two of them and the others to

be Negroes or white men disguised like

Negroes[.] (Minutes)

In North Carolina

politics, Edward

Mosley and Tobias Knight were bitter political

enemies. It went back to the Cary's

Rebellion when they were on opposite sides.

After Moseley heard about the Bell incident, he

devised a plan to link Blackbeard to Knight and thus

discredit Knight and possibly even Eden.

Moseley, or at least some of his agents, must have

traveled to Virginia to confer with Spotswood on the

issue of pirates in North Carolina and the inaction

on the part of Governor Eden. It is obvious that

Spotswood was in communication with Moseley because

when Captain Brand traveled to North Carolina in

November of 1718, he met Moseley in modern-day

Edenton and was then escorted to Bath by two of

Moseley’s associates. Brand wrote:

I reached

within 50 miles of Bath Town, on the 22nd. I got

my self and horses over the sound with the

assistance of Cols. Moseley and Capt. Moore two

Gent . . . I gott within three Mile of Town and

desired Capt. Moore to go in and Learn if Thach

was there, he soon return’d to let me know he

was not yet Come up but Expected Every minute. I

parted from Capt. Moors and went to the Governor

and applied my self to him and let him know I

was come in Quest of Thach. (Brand, 6

February)

At some point, Moseley

heard about the Bell incident. It might not have

meant anything to him at the time, but when news of

Blackbeard’s

death reached Moseley, he realized that it

could be turned to his advantage. He devised a

complicated scheme aimed at proving Knight’s

involvement with Blackbeard. The first part of this

scheme was to get Bell to change his story and to

name Blackbeard and four of his crew members as his

attackers. Apparently, Moseley was successful

because Bell testified against Blackbeard later at

the trial of the four crew members. This was the

most important aspect of Moseley’s plan. If

Blackbeard was the attacker, it would place

Blackbeard at the Knight house on the evening of 14

September. Moseley could then proclaim that

Blackbeard was there to make secret arrangements

with Knight for the disposal of the goods he had

recently taken from a French sugar merchant ship.

To be successful, Moseley’s entire scheme depended

upon getting corroborative testimony from some of

the members of Blackbeard’s crew. However, they were

all being held in Williamsburg. The only way for

Moseley to get that testimony was to get help from

Spotswood. Moseley’s agents worked closely with

Spotswood, providing the Virginia prosecutors with

the details of Bell’s assault and even some physical

evidence. Additionally, arrangements were made for

Bell to travel to Williamsburg and personally give

testimony. As a result, a trial of four of

Blackbeard’s pirates was scheduled in Williamsburg.

Proof of this first comes from the financial

arrangements that Spotswood made to have William

Bell travel to Williamsburg. Apparently, Bell lost

two horses along the way, which were eventually paid

for by the Virginia Council.

That your

Petitioner was at the charge of Supplying the

Government with Horses particularly for one Bell

and his Son Evidences against Blackbeards Crew

of Pirates taken in North Carolina Who were

tryed here by a Court of Admiralty, in Which

Service your Petitioner Lost two horses Which

cost him twenty pounds Currant Money and hath

received no Satisfaction for the Same[.] (Irwin)

The rest of the proof

comes from the transcript of the trial itself. Even

though the trial records were lost in Virginia,

Spotswood sent a transcript to the Governor of North

Carolina. The transcript launched a Council hearing.

Everything was carefully recorded and the original

still exists in the archives of North Carolina. Of

the five Africans captured, four of them stood trial

on 12 March 1719. Those four members of Blackbeard’s

crew were identified as the men who were allegedly

with him that night of the attack. They were James

Blake, Thomas Gates, James White, and Richard

Stiles.

The four accused all pled guilty and gave details

about the attack. William Bell also added his

testimony. In addition, Hesikia Hands (incorrectly

named Israel in Johnson’s book) testified as a

witness for the prosecution. Hands was at Ocracoke

when the alleged assault occurred; however, he

testified that Blackbeard and the other four all

went to Bath the night of the fourteenth and

returned with stolen goods taken from Bell.

The trial wasn’t only about Blackbeard; it involved

Knight to the greatest extent possible. The icing on

the cake was a personal letter from Knight to

Blackbeard that Maynard had found on Blackbeard’s

sloop Adventure shortly after the battle at

Ocracoke. The letter was dated 17 November, which

was just five days before Blackbeard’s death. This

letter was introduced during the trial as evidence

of Knight’s involvement with Blackbeard. Included in

the transcript of the trial was a recommendation for

Knight to be tried in North Carolina.

Whereas it

has appeared to this Court Mr. Tobias Knight

Secty of North Carolina hath given Just cause to

suspect his being privy to the piracys committed

by Edward Thache and his crew and hath received

and concealed the effects by them piraticaly

taken whereby he is become an accessary

Its therefore

the opinion of this court that a Copy of the

Evidences given to this Court so farr as they

relate to the said Tobias Knights Behaviour be

transmitted to the Governor of North Carolina to

the end he may cause the said Knight to be

apprehended and proceeded against pursuant to

the directions of the Act of Parliament for the

more Effectual Suppression of Piracy. (Minutes)

It is obvious that the

five pirates hoped to be released if they testified

against their dead captain and pled guilty to the

charges. It didn’t work for the four Africans. They

were hanged in Williamsburg. The document that

Spotswood sent to North Carolina stated that the

four pirates were “Condemned and since Executed.” (Minutes)

If the extension of the King’s Pardon was available,

why didn’t these four pirates qualify? I believe it

was because they were tried for assault and theft at

their trial, not piracy. It’s subtle but within the

legal parameters. It is ironic that if the four

pirates had refused to confess to the assault, they

probably would have qualified for the pardon and

been released.

Hands was, of course, released for testifying for

the prosecution and because of the extension of the

pardon. This is another instance that Charles

Johnson got right.

The other

Person that escaped the Gallows, was one Israel

Hands, Master of Black-beard’s Sloop,

and formerly Captain of the same . . . .

(Johnson, 86)

The Final Six

This leaves Caesar and five others, besides Hands,

who were arrested in Bath: John Giles, Joseph Brooks

Jr., John Martin, Stephen Daniel, and Edward Salter.

Each would have qualified for the extension of the

pardon. Apparently, upon accepting the pardon, the

pirate had to pay five shillings. Spotswood wrote a

letter to Secretary Craggs, dated 26 May 1719. In

it, Spotswood complains about some of the pirates

not paying their fee. The most intriguing aspect of

this letter is that it mentions seven pirates who

have received their pardons, but only one, a

“Condemned Negro,” has paid the fee.

. . .

having never received the value of one penny

from any of the Pyrates that have either

Surrendered, or been pardoned here; And tho’

there have been 14 or 15 who Surrendered, and

had Certificates under the Seal of the Colony,

for w’ch the Clerk was allowed to demand five

Shillings a piece, yet I am well assured that no

more than five paid any thing at all; And of

Seven that have rec’d their pardons, only one

has paid the Attorney-Gen’l the common fee he

receives for making out the like pardons even

for a Condemned Negro, and he, too, was a person

of a very notorious Character for his Piracys,

and had his Money restored to him after he had

been Condemned, because there was no proof of

its being piratically taken . . . . (Official,

317)

Although no names are

mentioned, it seems to fit Blackbeard’s pirates

perfectly. The last statement obviously refers to

William Howard, who had £50 seized upon his arrest.

The seven pirates mentioned in this letter must be

William Howard, John Giles, Joseph Brooks Jr., John

Martin, Stephen Daniel, Edward Salter, and Caesar,

the “Condemned Negro.” Hands was released for

testifying for the prosecution.

This is strong circumstantial evidence that Richard

Greensail and John Carnes were executed in Hampton

by Captain Gordon before word of the pardon reached

him. If they weren’t executed, they would have been

sent to Williamsburg along with the rest and would

have been released when word of the pardon reached

the court. Considering that there were only “Seven

that have rec’d their pardons,” it seems that

Richard Greensail and John Carnes never made it to

Williamsburg. (Official, 317)

Unfortunately, Caesar, John Giles, Joseph Brooks

Jr., and Stephen Daniel disappeared from the

historical record. But John Martin and Edward Salter

were quite active in Bath after 1719.

John Martin was the son of Joel Martin, who was

among the first residents of Bath arriving in 1706.

Joel died on 24 October 1715. In his will, his son

John inherited 220 acres from his father. John sold

the plantation north of Glebe Creek on 11 July 1720,

and James Robbins witnessed the deed. As you may

recall, Robbins was arrested at Ocracoke as a member

of Blackbeard’s crew.

Edward

Salter was the most prominent of the pirate

survivors. His name first appeared in Bath’s

historical records in 1721, when he purchased two

town lots from Henry Rowell. The deed was witnessed

once again by fellow pirate James Robbins. In 1723,

Salter bought 640 acres, and on 12 November 1726, he

bought Governor Eden’s 400 acres of property and his

mansion from Robert Campaine for £600. By 1727,

Salter was referred to as a “merchant and gentleman”

and owned the largest periauger with sails in the

county along with a brigantine named Happy Luke.

(Norris, 164-165) In 1728, Salter bought six deeds

for 3,371 acres on the south side of the Pamlico

River. He died in January 1734, and his periauger

and brigantine were both mentioned in his will.

With dozens of twentieth- and twenty-first-century

authors blindly following Johnson and writing that

thirteen pirates were hanged in Williamsburg, one

nineteenth-century author got it right. This author

was Shirley Hughson, who wrote Blackbeard &

the Carolina Pirates, which was published in

Hampton, Virginia in 1894. Hughson wrote:

In March

of the following year (1719) [Spotswood] made a

full report of the matter to the Council, which

endorsed his action and ordered the prisoners

tried for piracy. The Council was not

precipitate in its course, however. They

considered postponing action until every member

could be present, but it was thought that all

doubtful points could be just as well discussed

before the court, and the trials were ordered to

proceed immediately. They were held at

Williamsburg, and four of the accused were

condemned and afterwards hanged. (Hughson,

78)

The source Hughson cites

is most interesting. This is exactly how it reads.

An attempt

to secure some details of these trials from the

Virginia Admiralty Court Records proved

fruitless. The clerk writes: “The earlier

records of this Court are in such a condition

that I fear that I cannot give you the

information asked for. I cannot even tell

whether they go back as far as 1719; they are

piled up in heaps in an upper room of the custom

house building, and have been in that condition

ever since the war. At the evacuation of

Richmond in the Great Fire, a large quantity of

papers and records of the United States Courts,

as well as of the General Court of the State of

Virginia, were totally destroyed. (Hughson,

fn5, 78-79)

If all the records were

truly lost, how did Hughson arrive at the number of

four pirates hanged? Perhaps there were a few

scholars still alive who had seen the documents

before their destruction.

Summary

of those captured

William Howard

|

Accepted extension of pardon

|

John Carnes

|

Probably hanged in Hampton

|

Joseph Brooks (2)

|

Accepted extension of pardon

|

James Blake

|

Hanged in Williamsburg

|

John Giles

|

Accepted extension of pardon

|

Thomas Gates

|

Hanged in Williamsburg

|

James White

|

Hanged in Williamsburg

|

Richard Stiles

|

Hanged in Williamsburg

|

Caesar

|

Accepted extension of pardon

|

James Robbins

|

Acquitted

|

John Martin

|

Accepted extension of pardon

|

Edward Salter

|

Accepted extension of pardon

|

Stephen Daniel

|

Accepted extension of pardon

|

Richard Greensail

|

Probably hanged in Hampton

|

Hezekiah (Israel) Hands

|

Accepted extension of pardon

|

Samuel Odell

|

Acquitted

|

Conclusion

Of the fifteen pirates arrested in North Carolina

and taken to Virginia, four of them were hanged in

Williamsburg. Interestingly, they were executed for

the robbery of William Bell, not for piracy. These

men were James Blake, Thomas Gates, James White, and

Richard Stiles.

Two of the pirates who participated in the battle of

Ocracoke, John Carnes and Richard Greensail, never

made it to Williamsburg because they were executed

in Kecoughtan.

James Robbins and Samuel Odell were acquitted

without standing trial.

The remaining seven – Joseph Brooks, John Giles,

Caesar, John Martin, Edward Salter, Steven Daniel,

and Hezekiah (Israel) Hands – plus William Howard

(who had been arrested several months earlier and

was in the gaol), were found guilty. However, they

were released in accordance with the revised royal

proclamation.

At least two of these men, Salter and Martin,

returned to Bath, North Carolina, where their names

appeared in legal documents as landowners. Howard

eventually purchased the island of Ocracoke.

Blackbeard’s story is perhaps the most complicated

pirate tale ever told. There is nothing

straightforward about it. Political intrigue

abounds. Challenging relationships within his crew

and between him and his partners add to the

complexity. Taking all this into account, it is

easily understandable how so many historians have

missed or confused some of the facts when writing

about Blackbeard’s pirates in Williamsburg.

Notes:

1.

From P&P’s editor: Period documents often give

Blackbeard’s actual name as Edward Teach, Tach,

Thach, or Thatch, depending on the writer.

Spelling was not uniform in the eighteenth

century.

2. From P&P’s editor: Anne

Jacobs, the author’s editor and research

assistant, tells me that “Adult Van Pelt” appears

in several original period documents as this

person’s first and last names. Although I checked

several sources that pertain to eighteenth-century

given names, I found none that list “Adult.” It is

possible that rather than being the man’s actual

name,” he either refused to give his birth name or

the authorities chose to use “Adult” to

differentiate this man from another person,

possibly a minor.

One transcribed version of original Executive

Journals for the colony of Virginia

indicates that Van Pelt’s first name was Aure.

(see page 496) The author did not find this

spelling in any consulted resource.

3. From P&P’s editor: The

quotation marks after each “20” stand for pounds

(£) and after the “0”, for shillings. The third

column represents pence. The underscoring after

the fourth line has been inserted by P&P’s

editor and does not appear in the original

document. The numbers below the underscoring

represent the total tally of rewards paid.

4. The original charge sheet is

housed in the Library of Virginia.

5. From P&P’s editor: This

table has been adapted for ease of reading on the

website. With the exception of Hezakiah Hands, the

other men were denoted as “Common Sailors.” In the

second list of pirates for which no reward was

paid, Husk, Curtis, Brookes, Miller, and Jackson

were denoted as “Common Sailors.” Formatting

issues prevented the exact duplication of the

document. However, a copy of the original document

can be found here.

6. According to Merriam-Webster,

“periauger” is an archaic variant of “piragua,”

which can be either a dugout or a two-masted boat

with a flat bottom.

Resources:

Bialuschewski,

Arne. “Daniel Defoe, Nathaniel Mist, and the

General History of the Pyrates,” The Papers of

the Bibliographical Society of America 98:1

(March 2004), 21-38.

The Boston News-Letter, 16 December to 23

December 1717.

The Boston News-Letter, 23 February to 2

March 1719.

Brand, Ellis. Account of Taking Blackbeard.

State Archives of North Carolina. PRO-ADM

1/1472 [72.992.1-4]. 6 February 1719.

Brand, Ellis. To Lordships from HMS Lyme

in Galleons Reach. Library of Virginia. ADM

1/1472 [Reel 166 subsection 11]. 14 July 1719.

British

Royal Proclamations Relating to America

1603-1783 edited by Clarence S.

Brigham. Burt Franklin, 1911.

Cooke, Arthur. “British

Newspaper Accounts of Blackbeard’s Death,” The

Virginia Magazine of History and Biography

61:3 (1953-1955), 304-307.

Cracherode, Anthony. Report on Petitions for

Rewards for Capturing Pirates. Letters.

Library of Virginia. SR01227.1248 117.ff.134-141.

18 March 1720.

Duffus, Kevin P. The Last Days of Black Beard

the Pirate. Looking Glass Productions, 2008.

Executive

Journals of the Colonial Council of Virginia,

vol. 3, edited by Henry R. McIlwaine. The Virginia

State Library, 1928.

Hughson, Shirley Carter. Blackbeard & the

Carolina Pirates. Port Hampton Press, 2000.

Irwin, Henry. Petition

to Council for Two Horses. Library of

Virginia. Folder 30, Box 45, Id 36138, Colonial

Papers. 23 December 1720.

Johnson, Charles, Captain. A

General History of the Pyrates, second

edition. T. Warner, 1724.

Konstam, Angus. Black Beard: America’s Most

Notorious Pirate. John Wiley & Sons,

2006.

Lee, Robert E. Blackbeard the Pirate. John

F. Blair, 1974.

Lyme Log, Kiquotan Rd., Virginia. State

Archives of North Carolina. Pro-Adm. 51/4250

[72.2278.102]. 8-29 November 1718.

Memorial Volume of Virginia Historical

Portraiture, 1585-1830 edited by Alexander

Wilbourne Weddell. The William Byrd Press, 1930.

Minutes of the North Carolina Governor’s

Council. North Carolina State Archives, 27

May, 1719.

Norris, Allen Hart. Beaufort County, North

Carolina Deed Book I, 1696-1729: Records of Bath

County, North Carolina. The Beaufort County

Genealogical Society, 2003.

The

Official Letters of Alexander Spotswood,

Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Virginia,

1710-1722. The Virginia Historical

Society, 1882.

Order

to Charge William Howard. Colonial

Papers. Library of Virginia. 29 October 1719.

Page, Courtney. “Did You

Know Pirates Were Granted a Pardon?” Queen

Anne’s Revenge Project Blog (5 September

2017).

Rankin, Hugh. The Pirates of North Carolina.

Division of Archives and History, North Carolina

Department of Cultural Resources, 1960.

Spotswood, Alexander. Capt. Tach’s

Quartermaster Apprehension and Trial.

Library of Virginia. CO5/1318 [41.ff.291-298]. 22

December 1718. (online

version)

“Spotswood Letter to Eden.” Alexander

Spotswood: Biographical Sketch. Virginia

Museum of History & Culture. F222.V81 M68 W

41. [1930 p. 150–151]. 7 November 1718.

Watson, Alan D. Bath: The First Town in North

Carolina. North Carolina Office of Archives

& History, 2005.

Woodard, Colin. The Republic of Pirates.

Harper Collins, 2007.

|

Robert

Jacob is an award-winning author and

lecturer who has been heavily involved in

living history interpretation and reenacting

for over fifty years. While researching

pirates, Robert realized that much of the

historical record was contradictory and

incorrect. In 2018, after a ten-year quest

for accurate information on pirates, he

compiled his findings in his first book, A

Pirate’s Life in the Golden Age of Piracy.

Originally from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

Robert achieved the rank of Chief Warrant

Officer 5 in the U. S. Marine Corps before

retiring to Florida, where fans attending

book signings and festivals inspired him to

write his second book, Pirates of the

Florida Coast: Truths, Legends, and Myths.

His third book, Blackbeard: The Truth

Revealed, is being released in the

summer of 2024.

For more information on this and his other

books, please visit his

website.

|

|

Copyright ©2024 Robert Jacob

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |

According to Bialuschewski, in 1932,

literary scholar John Robert Moore suggested that

According to Bialuschewski, in 1932,

literary scholar John Robert Moore suggested that  Fortunately,

when it comes to Blackbeard, many primary sources

are available.

Fortunately,

when it comes to Blackbeard, many primary sources

are available.

[T]he Lieutenant sailed back to

the Men of War in James River, in Virginia,

with Black-beard’s Head still hanging at

the Bolt-sprit End, and fiveteen Prisoners,

thirteen of whom were hanged. (Johnson, 86)

[T]he Lieutenant sailed back to

the Men of War in James River, in Virginia,

with Black-beard’s Head still hanging at

the Bolt-sprit End, and fiveteen Prisoners,

thirteen of whom were hanged. (Johnson, 86) That left

two white men who were combatants and participated

in the action against Gordon’s men, Richard

Greensail and John Carnes. A logbook entry from HMS

Pearl dated 28 January 1719, might reveal

their fates. Captain Gordon wrote:

That left

two white men who were combatants and participated

in the action against Gordon’s men, Richard

Greensail and John Carnes. A logbook entry from HMS

Pearl dated 28 January 1719, might reveal

their fates. Captain Gordon wrote: On

21 December 1718, King George extended his

proclamation. The following is an excerpt of the

proclamation.

On

21 December 1718, King George extended his

proclamation. The following is an excerpt of the

proclamation.