Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Stede Bonnet (continued)

'Give me Liberty or

Give me Death!'

On 30 October 1718, Attorney General

Richard Allein addressed the jury. He

explained what constituted piracy and

recapped how the defendants came to be

standing in the dock. Then he stressed

what was expected of them as they sat in

judgement.

You are bound by your

Oaths, and are obliged to act

according to the Dictates of your

Consciences, to go according to the

Evidence that shall be produced

against the Prisoners, without Favour

or Affection, Pity or Partiality to

any of them, if they appear to be

guilty of those Crimes they are

charged with. And you are not allowed

a latitude of giving in your Verdict

according to Will and Humor. (Tryals,

9) You are bound by your

Oaths, and are obliged to act

according to the Dictates of your

Consciences, to go according to the

Evidence that shall be produced

against the Prisoners, without Favour

or Affection, Pity or Partiality to

any of them, if they appear to be

guilty of those Crimes they are

charged with. And you are not allowed

a latitude of giving in your Verdict

according to Will and Humor. (Tryals,

9)

Since some

residents within Charles Town seemed to

sympathize with these ne’er-do-wells,

Allein made a point of explaining why such

thinking was wrong. Especially if it

concerned Stede Bonnet.

I am sorry to hear some

Expressions drop from private Persons,

(I hope there is none of them upon the

Jury) in favour of the Pirates, and

particularly of Bonnet; that he is a

Gentleman, a Man of Honour, a Man of

Fortune, and one that has had a

liberal Education. Alas, Gentlemen,

all these Qualifications are but

several Aggravations of his Crimes.

How can a Man be said to be a Man of

Honour, that has lost all Sense of

Honour and Humanity, that is become an

Enemy of Mankind, and given himself up

to plunder and destroy his

Fellow-Creatures, a common Robber, and

a Pirate?

Nay, he was

the Archipirata . . . or

the chief Pirate, and one of the first

of those that began to commit those

Depredations upon the Seas since the

last Peace.

I have an

Account in my hand of above

twenty-eight Vessels taken by him, in

company with Thatch, in the West-Indies, since the

5th Day of April last; and how many

before, no body can tell.

His Estate

is still a greater Aggravation of his

Offence, because he was under no

Temptation of taking up that wicked

Course of Life.

His

Learning and Education is still a far

greater; because that generally

softens Mens Manners, and keeps them

from becoming savage and brutish: but

when these Qualifications are

perverted to wicked Purposes, and

contrary to those Ends for which God

bestows them upon Mankind, they become

the worst of Men, as we see the

present Instance, and more dangerous

to the Commonwealth. (Tryals,

9-10)

Thomas Hepworth

spoke as well. In addition to doing their

duty, he advised the jury to reflect on

just what kind of nuisance pirates in

general had been to Charles Town and its

trade. He also made known what he thought

of these men, who had taken the King’s

pardon and then resumed pillaging.

[C]onsider how long our

Coasts have been infested with

Pirates, (for the name of Men they do

not deserve) and how many Vessels they

have taken and pillag’d belonging to

this Place, as well as multitudes of

others belonging to divers parts of

his Majesty’s Dominions, and how many

poor Men in whose Blood they have

imbru’d their hands with the greatest

Inhumanity imaginable, and how many

poor Widows and Orphans they have

made, and how many Families they have

ruin’d, and how long they have gone on

in their abominable Wickedness: Nay,

do but consider how those very Pirates

lately insulted this Government, when

they sent for Medicines, threatning to

destroy our Vessels and Men in case of

refusal; nay, since these have

accepted of Certificates from the

Government of North Carolina,

like Dogs to their Vomits, they have

returned to their old detestable way

of living, and since taken off these

Coasts thirteen Vessels belonging to British

Subjects. (Tryals, 11)

When he

finished, the Crown called Ignatius

Pell to the stand. Although a pirate

himself, he had received clemency in

exchange for testifying against his mates.

He had been held with Stede and David

Herriot, but no evidence has shown why he

didn’t escape with them. The most logical

reason would be that he was free to go

about his business once he testified, and

he wasn’t about to jeopardize that

liberty. Pell had served as Revenge’s

boatswain at least since they “came from

the Bay of Honduras.” (Tryals, 11)

He was also one of the men marooned by

Thache.

Maj. Bonnet came

with the Boat, and told us, as we were

on a Marroon Island, that he was going

to St. Thomas’s to get a

Commission from the Emperor to

go against the Spaniards a

Privateering, and we might go with

him, or continue there: so we having

nothing left, was willing to go with

him. (Tryals, 11)

Pell then

recounted the various prizes taken and the

plunder “traded.” He also made mention

that “Reeve’s Wife . . . and Captain

Read’s Son . . . we sent them on shore.”

Captain Manwareing, however, remained a

prisoner for “[a]bout ten Weeks.” (Tryals,

12)

The pirates being tried that first day

were given the opportunity to question the

witness, but none did. So, the clerk of

the court called Captain Thomas Read to

the stand. First, he testified about a

capture that he witnessed.

The Sloop

Revenge was at an Anchor, and

the Scooner lay a long-side of her. I

was then a Prisoner on board of the

Sloop Revenge. In the Evening

we saw a Sloop coming into the Bay,

and Major Bonnet sent off

five Hands with the Dory; and about an

Hour after they came on board the Revenge,

and brought Capt. Manwareing.

. . . Major Bonnet demanded

his Papers; and he gave them to him.

He asked him from whence he came? He

answered from Antegoa, and

bound for Boston. He asked him

what he had on board? He told him.

(Tryals, 12) The Sloop

Revenge was at an Anchor, and

the Scooner lay a long-side of her. I

was then a Prisoner on board of the

Sloop Revenge. In the Evening

we saw a Sloop coming into the Bay,

and Major Bonnet sent off

five Hands with the Dory; and about an

Hour after they came on board the Revenge,

and brought Capt. Manwareing.

. . . Major Bonnet demanded

his Papers; and he gave them to him.

He asked him from whence he came? He

answered from Antegoa, and

bound for Boston. He asked him

what he had on board? He told him.

(Tryals, 12)

When the clerk

of the court asked the prisoners if they

wanted to question Read, they replied, “We

desire nothing, but that he would speak

the Truth.” (Tryals, 13)

Next up was Captain Peter Manwareing, who

filled in the gaps of his taking.

When they came on board us,

we were at an Anchor. About Eight or

Nine of the clock in the Evening we

saw the Canoo coming: I ordered my Man

to hale them. He asked from whence

they came, and what Sloops they were?

They answered, Capt. Thomas

Richards from St. Thomas’s,

and Capt. Read from Philadelphia.

So we were glad to hear it; so hoped

all was well. But as soon as they came

up the Shrowds, they clapp’d their

Hands to their Cutlashes. Then I saw

we were taken: And I said, Gentlemen,

I hope, as you are Englishmen,

you’ll be merciful; for you see we

have nothing to defend our selves.

They told us they would, if we were

civil. (Tryals, 13)

The man who

actually allowed the pirates to come

aboard Manwareing’s sloop was James

Killing, the mate.

The Thirty first of July,

between Nine and Ten of the clock,

there running a strong Tide of Ebb, we

came to an Anchor about fourteen

Fathom of Water near Cape James.

In about half an Hour’s time I

perceived something like a Canoo . . .

I ordered the Men to hand down a Rope

to them [the pirates]. So soon as they

came on board, they clapp’d their

Hands to their Cutlashes; and I said

we are taken. So they curs’d and swore

for a Light. I ordered our People to

get a Light as soon as possible. So

they ordered our Captain immediately

to go on board the Revenge;

and accordingly was sent with two of

their own Hands; and I saw him no more

that Night. So when they came into the

Cabin, the first thing they begun with

was the Pine-Apples, which they cut

down with their Cutlashes. They asked

me if I would not come and eat along

with them? I told them I had but

little Stomach to eat. They asked me,

why I looked so melancholy? I told

them I looked as well as I could. They

asked me what Liquor I had on board? I

told them some Rum and Sugar. So they

made Bowls of Punch, and went to

Drinking of the Pretender’s Health,

and hoped to see him King of the English

Nation: Then sung a Song or two. (Tryals,

13)

With the Crown

having proven their case, Judge Trott

spoke.

You the Prisoners at the

Bar stand charged with Felony and

Piracy . . . The Evidences have

proved it home upon you . . . so that

it appears all of you took up with

this wicked Course of Life out of

Choice . . . what have you to say in

your Defence? (Tryals, 14)

Robert Tucker

and Edward

Robinson spoke of Stede’s offer to

go privateering. Neal Paterson was a bit

more vocal on what he experienced.

Thatch came on

board and carried away fourteen of our

best Hands, and marooned twenty-five

of us on an Island; and Maj. Bonnet came and

told his he was minded to go . . . a

privateering against the Spaniards; so I was

willing to go with him, and when I was

on board, he forced me to do what he

pleased, for it was against my will. Thatch came on

board and carried away fourteen of our

best Hands, and marooned twenty-five

of us on an Island; and Maj. Bonnet came and

told his he was minded to go . . . a

privateering against the Spaniards; so I was

willing to go with him, and when I was

on board, he forced me to do what he

pleased, for it was against my will.

Judge

Trott. Did not Thatch carry away

your Money and what you had besides of

Goods?

N.

Paterson. Yes.

Attor.

Gen. Was you not all ashore when

you received the Act of Grace?

N.

Paterson. Yes, Sir.

Attor.

Gen. Why had you not continued

ashore? Why did you join with Bonnet? or who

forc’d you to it?

N.

Paterson. But, Sir, it was in a

strange Land, and I had no Money, nor

nothing left, and I was willing to do

something to live; but it was against

my will to go a pirating.

Judge

Trott. If you were forced, and

took only Provisions, pray how did you

come to share so much Money and Goods

afterwards? . . .

N.

Paterson. I could not hinder the

rest from doing what they pleased; but

it was contrary to my Inclination. (Tryals,

14)

Unimpressed,

Judge Trott moved on to the next pirate.

He and the remaining defendants gave

similar responses, although Job Bayley’s

response to Trott’s question on why he

fought Colonel Rhett was “We thought it

had been a Pirate.” (Tryals, 15)

The judge’s disdain could be sensed in his

reply: “[H]ow could you think it was a

Pirate, when he had King George’s

Colours?” (Tryals, 15)

After this, the jury retired to consider

their verdict. They sequestered themselves

for two hours before rendering it. Job

Bayley, Neal Paterson, Edward Robinson,

William Scot, and Robert Tucker were found

guilty.

Eight more pirates were brought in: Samuel

Booth, Thomas Carman, William Hewet, John

Levit, William Livers, William Morrison,

John William Smith, and John Thomas. These

men would be tried by a different jury.

Each of the previous witnesses returned

and gave their testimonies.

When it came to speaking for themselves,

several pirates spoke. Smith did say that

what pirating he did “was against my

Will.” (Tryals, 16) Carman tried to

prove his innocence, saying Thache had

forced him into piracy. The only reasons

he went on board Stede’s vessel were

because he “shewed me the Act of Grace”

and “to get my Bread, in hopes to have

went where I might have had Business,” and

he “had not signed the Articles” before

they departed Topsail Inlet. Ignatius Pell

countered with “But you gave the Captain

your word that you would.” (Tryals,

16)

Thomas swore he had also

been forced after being pardoned; the only

problem was that he accepted his share of

the loot when the booty was divided. The

same was true for Livers. When the pirates

did speak up for themselves, their words

tended to condemn them rather than help

them. Thomas swore he had also

been forced after being pardoned; the only

problem was that he accepted his share of

the loot when the booty was divided. The

same was true for Livers. When the pirates

did speak up for themselves, their words

tended to condemn them rather than help

them.

In addressing the jury this time, Trott

said: “Gentleman of the Jury, I think I

need say but little on this matter.” (Tryals,

17) After which the jurors retired to

consider their verdict. Each defendant was

found guilty.

The next trial began on Friday morning, 31

October 1718. The men standing in the dock

this time were Alexander Annand, George

Dunkin, William Eddy, Matthew King, Thomas

Nichols, Daniel Perry, John Ridge, George

Ross, and Henry Virgin. While the pirates

were different, the jury, the witnesses,

and the evidence for the third trial were

the same as the first. The one exception?

Defendant Nichols’s actions differed from

those of the others.

Ignatius Pell declared,

that Nichols . . . was very

much discontented; but Maj. Bonnet

said he would force him to go.

However, he would not join with the

rest of the Men, but always separated

himself from the Company.

Capt. Read said, that

Nichols behaved

himself different from the rest, and

did not join with them.

Capt. Manwareing

said, that

Nichols . . . said

. . . he hoped to get clear of them,

and looked very melancholy, and never

joined with the rest in their Cabals

when they were drinking: and when Maj.

Bonnet sent for

him, he refused to go, and said, he

would die before he would fight.

. . .

Killing.

. . . he told me, he would give the

whole World if he had it, to be free

from them; and when . . . Maj. Bonnet

sent for him, he refused to go . . .

till he sent to fetch him by force,

and then he told me he would not fight

if he did lose his Life for it: and he

was not with them when they shared . .

. and he never was at their Cabals, as

the rest were. (Tryals, 18)

On hearing all

these witnesses, Judge Trott believed that

Nichols had been forced. When Eddy tried

to use a similar defense, Trott scoffed at

his “I never acted in it.” The judge told

the defendant,

That is no Excuse: it is

not such or such a one that goes on

board only, but those that stand ready

to assist them, have as great a hand

in the Fact as the other; for Men

would not be taken by two or three, if

they had no more help: so that the

whole Crew are equally concern’d at

such a time. (Tryals, 18)

Annand thought

he would die if he had not joined; the

others put forth mitigating factors, but

based on their answers to questions put to

them, they proved themselves to be as

culpable as Eddy according to Judge

Trott’s line of thinking.

This time, when the jury returned from its

deliberations, they found all but one

defendant guilty of the charges against

them. Thomas Nichols was deemed “Not

Guilty.” (Tryals, 20)

The next batch of pirates to be tried were

Zachariah Long, John Lopez, James Mullett,

James Robbins, Thomas Price, and James

Wilson. Wilson pleaded guilty, so he was

returned to the Watch

House. The rest listened to each

witness who took the stand. Again, the

witnesses and the proceedings were a

repeat of the previous trials. Robbins

said in his defense that “I was on board

the Revenge, and then I was sent

on board of Capt. Read’s Sloop,

and was there four Days; and then was sent

on board the Revenge again. So I

was about to run away, if I had an

Opportunity.” (Tryals, 20) His

defense proved sufficient because the jury

came back with a verdict of innocence; the

others were guilty.

A bystander might expect that sentences

would be pronounced next; instead, the

pirates faced second trials, this time for

the seizure of Captain Thomas Read’s

sloop. The first was held on Saturday

morning and pertained to the participation

of Bayley, Carman, Paterson, Robinson,

Scot, Smith, Tucker, and Thomas. The same

jury that had sat in judgment of them the

first time, did so this time as well. The

evidence given was basically the same; so

was what the pirates had to say for

themselves. Again, all were judged guilty

of the charged crime.

The next group was brought before the

bench the same day. The same members of

the jury from the first session heard this

case too. The evidence presented was much

the same as earlier, but Thomas Nichols’s

behavior and actions became a focal point.

Pell informed the court that “Nichols was

very much dissatisfied . . . and did not

join with the rest of the Company, and

would not take the Share . . . .” (Tryals,

24)

As for Manwareing, he said,

When Nichols was

on board my Sloop, he said several

times he would get clear of them the

first Opportunity, and he hoped it

would not be long first; and when

Major Bonnet sent for all

Hands on board the Revenge, he refused

to go, till he sent word, If he would

not come, he would make him; and when

he went, he said, Before he would

fight, he would die: and he always

kept himself from the Company, and

from their Cabals. (Tryals,

24)

Once again,

Killing and Captain Read concurred with

the other witnesses’ testimonies. The only

difference this time around was that

George Dunkin kept trying to convince the

jury that his case was similar to

Nichols’s. In fact, Read initially

considered him to be a captive of the

pirates, but the longer he was with them,

the less he believed this to be so. Pell

verified that Dunkin did accept a share of

the plunder. When given the chance to

offer a defense, Dunkin provided a

“Testimony of his former Behaviour when in

Scotland.” (Tryals, 26) Regardless,

the outcome of this trial was the same:

all but Nichols were deemed guilty.

The court reconvened on Monday, 3 November

to try Long, Lopez, King, Mullet, Perry,

Price, Ridge, Robbins, Virgin, and Wilson.

There were a few minor differences with

this trial. Three jurors were new. There

was a new witness, Francis Griffin. What

remained the same was that all the pirates

were found guilty.

Next to be tried were Robert Boyd, John

Brierly, Jonathan Clarke, Thomas Gerrard,

and Rowland Sharp. They all denied being

guilty of the charges. Manwareing, and the

other witnesses to lesser degrees,

testified that “my Man Garrard .

. . told me, he was not able to bear any

longer, but was forced to comply with

them, for they told him they would . . .

make a Slave of him; but he did not

receive any of their Goods: and when he

was at home, he had the Character of an

honest Man, and fought for his King and

Country.” (Tryals, 30)

Brierly claimed not to have participated

in piracy.

Mr. Boyd and I was in a

leaky Canoo, and we were afraid she

would sink . . . I stood up and . . .

saw . . . a Vessel . . . They sent off

their Dory, and asked if we would

consent to go with them? And we said

no: but they said they would break the

Canoo . . . they made me consent to go

on board the Revenge, but I

never joined myself while I was on

board: and then I was ordered on board

Capt. Manwareing, and there I

worked; but I never bore Arms, nor did

not fight Col. Rhett. (Tryals,

30)

Sharp also

claimed to have been forced.

After I was taken, I went

on shore, and travell’d four days in

the Woods without eating or drinking,

and could find the way to no

Plantation, and so was forced to

return again, and I refused to sign

the Articles; and one of the Men came

and told me I was to be shot . . . but

I was resolved to make my escape the

first Opportunity. (Tryals,

30)

Clarke’s story

was similar. He refused to sign the

articles or work the pumps, even though

that was the task assigned to him. If he

didn’t comply, Stede “told me . . . he

would make me Governor of the first Island

he came to; for he would put me ashore,

and leave me there.” (Tryals, 30)

This time, when the jury revealed their

verdicts, Clarke, Gerrard, and Sharp were

innocent. Brierly and Boyd were condemned.

These same pirates faced their second

trial on Tuesday, 4 November. This time

around only Brierly was found guilty.

The next day, all the pirates were brought

before Judge Trotter and the rest of the

vice-admiralty court. All of those named

below had been judged guilty of at least

one act of piracy. (One was sufficient to

earn the hangman’s noose.)

Pirate

|

Home Port

|

| Alexander Annand |

Jamaica |

| Job Bayley |

London, England |

| Samuel Booth |

Charles Town, South

Carolina |

| Robert Boyd |

Bath Town, North

Carolina |

| John Brierly |

Bath Town, North

Carolina |

| Thomas Carman |

Maidstone, Kent, England |

| George Dunkin |

Glasgow, Scotland |

| William Eddy |

Aberdeen, Scotland |

| William Hewet |

Jamaica |

| Matthew King |

Jamaica |

| John Levit |

North Carolina |

| William Livers |

Dublin, Ireland |

| Zachariah Long |

Holland, The Dutch

Republic |

| John Lopez |

Oporto, Portugal |

| William Morrison |

Jamaica |

| James Mullet |

London, England |

| Neal Paterson |

Aberdeen, Scotland |

| Daniel Perry |

Guernsey, Channel

Islands |

| Thomas Price |

Bristol, England |

| John Ridge |

London, England |

| James Robbins |

London, England |

| Edward Robinson |

Newcastle upon Tyne,

England |

| George Ross |

Glasgow, Scotland |

| William Scot |

Aberdeen, Scotland |

| John-William Smith |

Charles Town, South

Carolina |

| John Thomas |

Jamaica |

| Robert Tucker |

Jamaica |

| Henry Virgin |

Bristol, England |

| James Wilson |

Dublin, Ireland |

In his address

to these men, Judge Trott said,

You cannot but acknowledge

that you have all . . . had a fair and

indifferent Tryal.

You were

fully heard, not only as to all you

could pretend to say in your own Defences, but also

as to what you alledge in Mitigation of your

Crimes.

And

indeed, when you saw that the Facts

laid in the Indictments were

so fully proved against you, tho most

of you pleaded Not Guilty . .

. yet in the open Court . . . most of

you acknowledged the Facts charged

upon you. Therefore no one can think

but that you were all . . . justly

found Guilty; and your own

Consciences will oblige you to

acknowledge the same. (Tryals,

34)

He went on to

talk about the wayward path they had

followed, quoting apt scripture to

emphasize certain points. He hoped they

would take what little time was left to

them to truly consider what they had done

and to truly repent, for that was the only

way in which their souls would be

redeemed.

Thus having discharged

my Duty to you as a Christian . . . I

must now do my Office as a Judge. Thus having discharged

my Duty to you as a Christian . . . I

must now do my Office as a Judge.

The Sentence that the

Law hath appointed to pass upon you

for your Offences, and which this

Court doth therefore award, is,

That you . .

. shall go from hence to the place from

whence you came, and from thence to the

place of Execution, where you shall be

severally hanged by the Neck, till you

are severally dead.

And the God

of infinite Mercy be merciful to every

one of your Souls. (Tryals, 36)

Also present

were Jonathan Clark (Charles Town, South

Carolina), Thomas Gerrard (Antigua),

Thomas Nichols (London, England), and

Rowland Sharp (Bath Town, North Carolina).

Since they had been found not guilty, they

were permitted to walk free.

Three days later, on Saturday 8 November,

the condemned prisoners were taken to White

Point and executed.6

Just Desserts

So,

where was Stede Bonnet all this time? He

and David Herriot opted to make their

getaway during the night of 24 October,

three weeks after their arrest. Stede did

it in style by donning women’s attire

before they slipped away from Provost

Marshal Partridge’s home.7

Of course, rumors of collusion immediately

surfaced. How else could the pair have

escaped? Although no evidence was found,

it was thought the sentries had been

bribed to look the other way. At the very

least, one abettor in the escape was a

local resident named Richard

Tookerman. He provided Stede and

Herriot with firearms, ammunition, and a

canoe as well as the three slaves to row

it. When Governor Johnson’s offer of a

reward failed to produce results, he

summoned Colonel Rhett to track down Stede

and David. So,

where was Stede Bonnet all this time? He

and David Herriot opted to make their

getaway during the night of 24 October,

three weeks after their arrest. Stede did

it in style by donning women’s attire

before they slipped away from Provost

Marshal Partridge’s home.7

Of course, rumors of collusion immediately

surfaced. How else could the pair have

escaped? Although no evidence was found,

it was thought the sentries had been

bribed to look the other way. At the very

least, one abettor in the escape was a

local resident named Richard

Tookerman. He provided Stede and

Herriot with firearms, ammunition, and a

canoe as well as the three slaves to row

it. When Governor Johnson’s offer of a

reward failed to produce results, he

summoned Colonel Rhett to track down Stede

and David.

One might think the pair would have

vamoosed, but as often happened, best laid

plans went awry. The weather failed to

cooperate. The promised provisions never

arrived. Nor did the more seaworthy sloop

from Tookerman. This left the escapees

with few options, so they went to Sullivan’s

Island, established a campsite, and

Stede wrote a letter of complaint, which

two of the slaves were to deliver to

Tookerman.

What Stede hadn’t foreseen was that an

eagle-eyed watchman, patrolling Charles

Town, recognized the two messengers. When

they were searched, Stede’s letter was

discovered. The contents of the missive

are unknown, but the authorities now knew

who was in league with the pirates.

Bringing Tookerman to justice proved

elusive. There was insufficient proof and

his slaves could not testify against him

in court according to the law. Therefore,

he remained at large.8

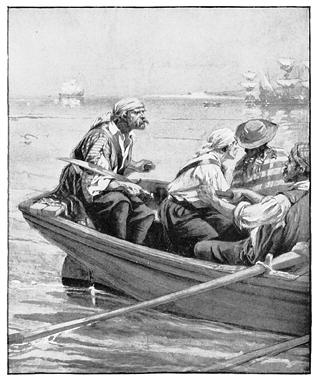

Howard Pyle, 1894

(Source: Dover's Pirates CD)

Not so Stede

and David. Rhett quickly found the

pirates’ hideaway and went in firing.

David was killed in the skirmish; the

hunters “wounded one Negroe and

an Indian.” (Tryals, vi)

Realizing the gig was up, Stede

surrendered again. He arrived back in

Charles Town two days before his men were

hanged. This time around, he was kept

under careful guard to prevent a second

escape.

Two days after the hangings, Stede came

before the vice-admiralty court to answer

for his crimes. On that Monday, he was

arraigned on two charges of “feloniously

and piratically taking” Captain Peter

Manwareing’s Francis and Captain

Thomas Read’s Fortune, as well as

cargo that these sloops carried. (Tryals,

37) Stede maintained his innocence and

pled not guilty.

Rather than waste more

time, Judge Trott proceeded with the first

trial. The following jurors heard this

case: Henry Beaton, Thomas Bee, Timothy

Bellamy (foreman), Benjamin Dennis, George

Ducket, Claas Joor, Thomas Lamboll, John

Lee, Jonathan Main, James Mazyck, William

Sheriff, and Moses Wilson. Only half of

the jurors were serving for the first

time. The rest were sitting in judgment

for the sixth time. Bellamy, one of those

six, had also served as the foreman on

five previous trials. Rather than waste more

time, Judge Trott proceeded with the first

trial. The following jurors heard this

case: Henry Beaton, Thomas Bee, Timothy

Bellamy (foreman), Benjamin Dennis, George

Ducket, Claas Joor, Thomas Lamboll, John

Lee, Jonathan Main, James Mazyck, William

Sheriff, and Moses Wilson. Only half of

the jurors were serving for the first

time. The rest were sitting in judgment

for the sixth time. Bellamy, one of those

six, had also served as the foreman on

five previous trials.

Prosecuting attorney Hepworth opted to

focus on the part Stede played in David

Herriot’s demise, which resulted in the

loss of a witness against the pirates. As

far as Hepworth was concerned, Stede was

“answerable for that Man’s Death.” (Tryals,

37) Hepworth also highlighted Stede’s

ill-fated decision during the time in

which Thache had command of Revenge.

[S]ome People took

particular notice of the Prisoner’s

Behaviour at the time when . . . he

began to reflect upon his past Course

of Life, and was filled then with such

Horror, that he was perfectly

confounded with Shame at the many

detestable Crimes he had been guilty

of, and said, he would gladly leave

off that way of living, being fully

tired, and having got considerably by

it; but he should be ashamed ever to

see the Face of an Englishman:

therefore, if he could not get to

Spain or Portugal, where he might be

undiscover’d, he would live and die in

the same Course of Life, viz. in

Piracy and Robbery. (Tryals,

37)

Hepworth

didn’t feel a simple trial was sufficient.

After all, Stede “was the great Ringleader

. . . who . . . seduced many poor

ignorant Men . . . and ruined many poor

Wretches; some of whom lately

suffered, who to the last Breath

expressed a great Satisfaction at the Prisoner’s

being apprehended, and charged the

ruin of themselves and loss of their Lives

intirely upon him.” (Tryals, 37-38)

With that opening, the Crown’s first

witness, Ignatius

Pell, was called to the stand. Mr.

Hepworth and the attorney general

questioned him about what the pirates did

while he sailed with Stede, especially as

it pertained to Manwareing. At one point,

Judge Trott asked whether Stede was Pell’s

commander, and the witness’s response was,

“He was called our Captain to be sure.” (Tryals,

38) Later, he qualified this by saying,

“He went by that Name; but the

Quarter-Master had more Power than he.” (Tryals,

38) As far as Trott was concerned,

however, the point of fact was that Stede

“was Commander in Chief,” which meant he

was the one in charge. (Tryals, 38)

Next to testify was Captain Manwareing.

After the prosecution established that

there had been a piratical attack on his

vessel, Bonnet was permitted to ask

questions.

Bonnet. I

beg leave to ask whether you ever saw

me share among the rest.

Manwareing.

You was in the Round-House, and a

Bundle and some Pieces was brought;

and I saw you take it, and give it the

Negroe-Boy, to put into the Chest.

Bonnet.

There was several that I kept their

Shares for; but it was not mine.

Manwareing.

It was put away by your Order.

Bonnett.

Did you ever here me order any thing

out of the Sloop?

Manwareing.

Major Bonnet, I am sorry you

should ask me the Question; for you

know you did: Which was my All, that I

had in the World. So that I do not

know but my Wife and Children are now

perishing for want of Bread in New-England.

Had it been only my self, I had not

matter’d it so much; but my poor

Family grieves me. (Tryals,

39)

That response

ended Stede’s desire to pose any further

questions, and Hepworth called James

Killing to the stand. He basically

repeated what he had testified to in

earlier trials. This time, Attorney

General Allein wished to make it clear

that Stede had given orders for the

removal of cargo, and Killing said without

question, it was “Major Bonnet gave

Orders for it to be done.” (Tryals,

39)

Since Stede had no questions for Killing,

Captain Read took the stand. His

information confirmed statements made by

the previous two witnesses. Again, Stede

had nothing further to ask. The

prosecution rested and Judge Trott

informed Stede that he could now mount his

defense. Stede called “a young Man came

from North Carolina, that will say

something in my Defence.” (Tryals,

40) His name was James King. It turned out

that what the lad had to say was basically

hearsay. After listening to the testimony,

Judge Trott wondered whether “this be all

the Evidence you have.” If so, “I do not

see this will be of much use to you . . .

.” (Tryals, 40) King was dismissed.

At this point, Stede wanted to address the

court on both indictments, but Trott would

only permit him to speak on the charge for

which he was currently being tried.

. . . though I must

confess my self a Sinner, and the

greatest of Sinners, yet I am not

guilty of what I am charged with. As

for what the Boatswain says,

relating to several Vessels, I am

altogether free; for I never gave my

Consent to any such Actions: For I

often told them, if they did not leave

off committing such Robberies, I would

leave the Sloop; and desired them to

put me on shore. And as for taking

Capt. Manwareing, I assure

your Honours it was contrary to my

Inclination . . . I opposed it, and

told them again I would leave the

Sloop . . . . (Tryals, 40)

After a brief

discourse between Stede and Judge Trott,

Attorney General Allein’s closing remarks

were designed to refute Stede’s defense

and remind the jurors of his own case.

[T]he Boatswain,

who seems to bear a very great

Affection to him, yet he tells you

that he was Commander in chief among

them at the time when Capt. Manwareing

was taken. Capt. Manwareing tells

you . . . he was brought before him,

and no other, and that he delivered

his Papers to him; and he saw his

Share brought to him . . . and put

into the Chest. (Tryals,

40)

In other

words, what more proof do you need? After

considering the verdict, the jury foreman

announced that they “found . . . Stede

Bonnet alias Edwards, alias

Thomas, Guilty.” (Tryals,

41) With that, Trott adjourned court for

the day and Stede was returned to his

prison.

On Tuesday, 11 November, court reconvened

with the intention of trying Stede on the

second indictment against him. Instead, he

changed his plea to guilty. Judge Trott

postponed further business until the next

day.

When Stede appeared at the bar on

Wednesday, Judge Trott remarked on the

fact that although Stede stood guilty on

two acts of piracy, he could easily “have

been . . . convicted of eleven more

. . . .” (Tryals, 42)

Trott then proceeded to spell out the sins

that Bonnet was guilty of and, being a

biblical scholar, the judge quoted

appropriate Bible verses to bring home his

points. For example:

And consider that Death

is not the only Punishment due to Murderers;

for they are threaten’d to have

their Part in the Lake

which burneth with Fire and

Brimstone, which is the

second Death, Rev.

21.8. See Chap. 22.15. (Tryals,

42)

He also spoke

about education.

You being a Gentleman

that have had the Advantage of a

liberal Education, and being

generally esteemed a Man of

Letters . . . considering the Course

of your Life and Actions, I have just

reason to fear that the Principles of

Religion that had been instill’d into

you by your Education, have

been at least corrupted, if not

entirely defac’d, by the

Scepticism and Infidelity of

this wicked Age; and that what Time

you allowed for Study was rather

applied to the Polite Literature,

and the vain Philosophy of

the Times, than a serious Search after

the Law and Will of

God . . . . (Tryals, 42)

Trott went on

like this for a time and then spoke of

redemption before pronouncing Stede’s

death sentence.

Initially, Stede accepted his fate with “a

demeanor of calm dignity, not to say

indifference.” (History, 181) This

changed after he learned the date of his

execution, which had been set by the

governor. Now, knowing he would hang on 10

December, Stede “became unnerved.” (History,181)

Not everyone in town was happy with the

outcome of Stede’s trial. His supporters,

especially some women, favored pardoning

him. Even Colonel Rhett proposed that he

could escort Stede to London, where King

George III might weigh in on what was to

become of this gentleman turned pirate.

But those in authority, including Governor

Johnson, had had enough. The king would

not be consulted in this matter. Hanging

Stede was the perfect means for showing

others just what to expect if they even

considered stepping away from the straight

and narrow.

Still, Stede wasn’t above begging for his

life as shown in the letter he sent to the

governor.

I have presumed on the

confidence of your eminent Goodness to

throw myself after this manner at your

feet, to implore you’ll be graciously

pleased to look upon me with tender

Bowels of Pity and Compassion; and

believe me to be the most miserable

Man this day breathing; That the tears

proceeding from my most sorrowful soul

may soften your heart, and incline you

to consider my dismal State . . . [I]

therefore beseach you to think me an

object of your Mercy.

. . .

I intreat

you not to let me fall a Sacrifice to

the Envy and ungodly rage of some few

Men, who, not yet being satisfied with

Blood, feign to believe that if I had

the Happiness of a longer Life in this

World I should still employ it in a

wicked Manner . . . I heartily beseach

you’ll permit me to live, and I’ll

voluntarily put it ever out of my

power by separating all my Limbs from

my Body, only reserving the use of my

Tongue to call continually on and pray

to the Lord, my God, and mourn all my

Days in Sackcloth and Ashes to work

out Confident hopes of my Salvation,

at that great and dreadful Day when

all righteous Souls shall receive

their just rewards. (History,

181-182)

Stede was even

willing to serve an indenture for the rest

of his life, if only he were spared

dancing the hempen jig. If mercy wasn’t

possible, he did say he would “pray that

our heavenly Father will also forgive your

Tresspasses.” (History, 182) He

signed his letter,

Your Honour’s Most

miserable and Afflicted Servant Stede

Bonnet. (History, 182)

A second

missive from Stede was sent on 27

November. The recipient was said to be

Colonel William Rhett, the man who had

captured him (twice), but some wording

suggests it was sent to a third party.

My unhappy fate lays me

under a necessity of troubling you

with this letter, which I humbly beg

you will be pleased to excuse, and

with a tenderness of heart

compassionate the deplorable

circumstances I have been

inadvertently led into; and though I

can’t presume to have the least

expectations of your friendship for so

miserable a man, yet I hope your good

disposition and kind humanity will

move you to become an intercessor with

his honor the Governor, that I may be

indulged with a reprieve to stay

execution of the severe sentence I

have undergone, till his majesty’s

pleasure be known concerning me.

(Ramsay, 116 n.)

He did talk some about his

time with Thache,

claiming to have been “a prisoner on

board” and that Thache “with several of Captain

Hornigold’s company which he then

belonged to, boarded and took my sloop

from me at the island of Providence,

confining me with him eleven months[.]”9

(Ramsay, 116 n.) He swore he didn’t

participate in the pirates’ endeavors and

that he received no shares from the

captured prizes. He did talk some about his

time with Thache,

claiming to have been “a prisoner on

board” and that Thache “with several of Captain

Hornigold’s company which he then

belonged to, boarded and took my sloop

from me at the island of Providence,

confining me with him eleven months[.]”9

(Ramsay, 116 n.) He swore he didn’t

participate in the pirates’ endeavors and

that he received no shares from the

captured prizes.

. . . I can’t but confess

my crimes and sins have been too many,

for which, I thank my gracious God for

the blessing, I have the utmost

abhorrence and aversion; and although

I am become as it were a monster unto

many, yet I intreat your charitable

opinion of my great contrition and

godly sorrow for the errors of my past

life . . . (Ramsay, 116 n.)

He promised

that he had no intention of ever allowing

himself to be brought so low again and

would “follow those excellent precepts of

our holy Savior – to love my neighbor as

myself; and do unto all men whatsoever I

would they should do unto me, living in

perfect holy friendship and charity with

all mankind.” (Ramsay, 117 n.)

According to Stede, he was the one who

convinced his fellow pirates to surrender

to Colonel Rhett, but it took him “near

twenty-four hours time and trouble to do

after the engagement was over, when I knew

what the two sloops were that Colonel

Rhett commanded.” (Ramsay, 117 n.) Thus

Stede was the one who had spared everyone

more bloodshed and prevented some of the

pirates from carrying out their threat to

blow up Revenge should Rhett and

his men board the pirate ship. He was

certain that Rhett would so testify should

Stede receive his reprieve and be taken to

England.

He did understand that his escape “might

justly increase and aggravate his honor

and” those in authorities. (Ramsay, 117

n.) He chalked up his doing so to the fact

that anyone in his dire circumstances

would want “to evade, if possible, so

horrid a sentence, by endeavoring to get

to some private settlement and continue

there till my friends could apply home for

his majesty’s gracious pardon.” (Ramsay,

117 n.)

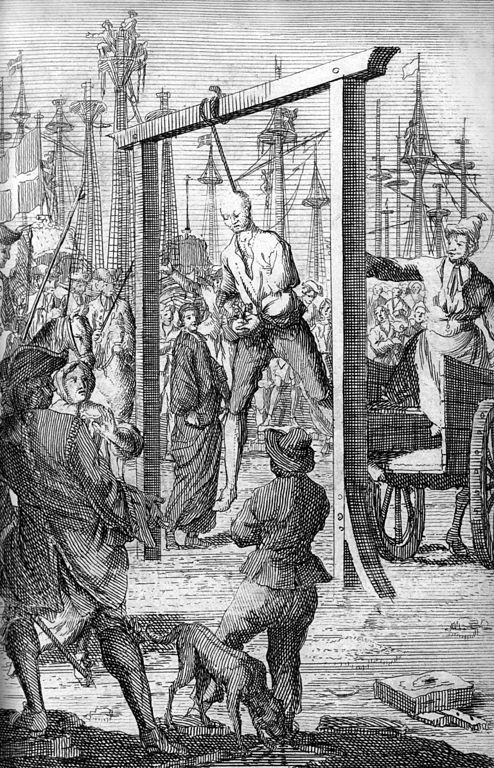

As they say, the rest is history. The

governor did not stay the execution; nor

did he acquiesce and allow anyone to put

Stede’s case for leniency before the king.

A pirate was a pirate, and pirates needed

to be punished. Hence, on 10 December

1718, Stede Bonnet breathed his last. He

was carted, under close

guard, to the gallows at White Point.

. . . Approaching the gallows, Bonnet

clutched a wilted bouquet of flowers .

. . in his shackled hands. (Moss,

174-175)

Majoor Stede Bonnet

Gehangen

(The Hanging of Major Stede Bonnet)

Engraving from 1725 Dutch edition of

Captain Charles Johnson's A

General History of the Pyrates

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

As for those he left behind, he “never

expressed feelings of regret or sorrow.”10

(Moss, 175)

The impression often given of Stede Bonnet

is of a man who was inept at pirating, yet

in 2008, Forbes included him in

their list of “The 20 Highest-Earning

Pirates.” His takings equated to $4.5

million (2008 dollars), making him number

fifteen. He surpassed Richard Worley,

Charles Vane, Edward Low, John Rackham

(Calico Jack), and James Martel.

Notes:

6. What

happens when a person is guilty of one

crime and not the other? These were the

verdicts rendered at Boyd's two trials.

In this instance, he was sentenced to

death. At some point thereafter, he was

given a reprieve and did not dance the

hempen jig.

Nor was he the only one spared, despite

being found guilty. Twenty-nine were

destined for the hangman's noose; only

twenty-two met that fate. The reprieved

were Brierly, Carman, Levit, Livers,

Ridge, and Wilson.

7. Nathaniel

Partridge would lose his job because of

the escape.

8. Although

Tookerman eluded authorities for his

part in Stede’s escape, he landed in

jail the following March because stolen

evidence was found in his possession. He

later escaped and made his way to

Barbados. There, he went on the account.

Captured in Port Royal for visibly

supporting the Jacobite cause, he was

taken to England to stand trial. Instead

of being prosecuted, the Court of King’s

Bench released him. Believing he had

been falsely arrested, he sued Admiral

Edward Vernon, who had signed the

orders for his arrest and transport from

Jamaica. Tookerman felt £10,000 was just

compensation; Vernon was going to ignore

the whole affair until his lawyers

advised otherwise. Negotiations were

conducted and Tookerman walked away with

£800 instead.

9. Although captured

first, it’s interesting to note that

Stede outlasted his former “partner,”

Edward Thache. Lieutenant Robert Maynard

and his men caught up to Blackbeard on

22 November 1718. When the ensuing fight

ended, he was dead, having suffered

“five Shot in him, and 20 dismal Cuts in

several Parts of his Body.” (Brooks,

546)

10. Mary Bonnet, his

wife, lived until 1750. Her estate was

shared among their surviving children:

Edward, Stede, and Mary.

Resources:

“The

Affidavit of Capt. Peter Manwareing” in The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet. Printed for

Benj. Cowse, M. DCC.XIX., 50.

“America

and West Indies: January 1718, 1-13” in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. His

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1930. (Jan.

6. 298.)

“America

and West Indies: May 1718” in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. His

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1930. (May

31. Bermuda. 551)

“America

and West Indies: June 1718” in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. His

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1930. (June

18. Charles Towne, South Carolina. 556.)

“America

and West Indies: October 1718,” in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. His

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1930. (Oct.

21. Charles town, South Carolina. 730.)

Baker, Daniel R. “Stede Bonnet: The Phantom

Alliance,” The Pyrate’s Way (Summer

2007), 21-25.

Bialuschewski, Arne. “Blackbeard

off Philadelphia: Documents Pertaining to the

Campaign against the Pirates in 1717 and 1718,”

The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and

Biography v.134: no. 2 (April 2010),

165-178.

“Boston,” The Boston News-Letter 16 June

1718 (739), 2.

British Piracy in the Golden Age: History and

Interpretation, 1660-1730 edited by Joel

H. Baer (volume 2). Pickering & Chatto,

2007.

Brooks, Baylus C. Quest for Blackbeard: The

True Story of Edward Thache and His World.

Independently published, 2016.

Butler, Nic. “The

Watch House: South Carolina’s First Police

Station, 1701-1725,” Charleston Time

Machine (3 August 2018).

Cooper, Thomas. “An Act

for the More Speedy and Regular Trial of

Pirates. No. 390.” in The Statutes at

Large of South Carolina. Printed by A. S.

Johnston, 1838, 3:41-43.

Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag: The

Romance and the Reality of Life Among the

Pirates. Random House, 1995.

Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters:

The Epic History of America’s Most Notorious

Pirates. Liveright, 2018.

Downey, Christopher Byrd. Stede Bonnet:

Charleston’s Gentleman Pirate. The History

Press, 2012.

Fictum, David. “'The

Strongest Man Carries the Day,' Life in New

Providence, 1716-1717,” Colonies, Ships,

and Pirates (26 July 2015).

Hahn, Steven C. “The

Atlantic Odyssey of Richard Tookerman:

Gentleman of South Carolina, Pirate of

Jamaica, and Litigant before the King’s Bench,”

Early American Studies 15:3 (Summer 2017),

539-590.

History

of South Carolina edited by Yates Snowden.

Lewis Publishing, 1920, 1:173-182.

“The Information of Capt. Peter Manwareing” in The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet. Printed for

Benj. Cowse, M. DCC. XIX., 49.

“The Information of David Herriot and Ignatius

Pell” in The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet.

Printed for Benj. Cowse, M. DCC. XIX., 44-48.

Johnson, Charles. A

General History of the Pyrates. T. Warner,

1724.

Logan, James. “James

Logan letter to Robert Hunter, October 24,

1777." Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Discover.

(Special

note, the date of the entry is misleading as the

date of the letter [viewable and downloadable here]

is 24 8 1717 or 24 August 1717. James Logan was

deceased in 1777.)

The London

Gazette. Issue

5573 (14 September 1717), 1.

Marley, David F. “Thatch, Edward, Alias

‘Blackbeard’ (fl. 1717-1718),” Pirates of

the Americas. ABC-CLIO, 2010, 2:787-799.

Malesic, Tony. E-mail posting on PIRATES about

Richard Tookerman, 26 September 2001.

Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the

Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet.

Köehler, 2020.

Moss, Jeremy. “Stede

Bonnet, Gentleman Pirate: How a Mid-life

Crisis Created the ‘Worst Pirate of All Time,’”

History Extra (4 January 2023).

“Philadelphia, October 24th,” The Boston

News-Letter 11 November 1717 (708), 2.

“A Prefatory Account of the Taking of Major

Stede Bonnet, and the other Pirates, by the two

Sloops under the Command of Col. William Rhett”

in The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet.

Printed for Benj. Cowse, M. DCC. XIX., iii-vi.

Ramsay, David. Ramsay’s

History of South Carolina: From Its First

Settlement in 1670 to the Year 1808. W. J.

Duffie, 1858.

“Top-Earning

Pirates,” Forbes (19 September 2008).

The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other

Pirates. Printed for Benjamin Cowse,

MDCCXIX.

Woodard, Colin. The Republic of Pirates:

Being the True and Surprising Story of the

Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them

Down. Harcourt, 2007.

Copyright ©2024 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |