Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Transformation

A Family Affair

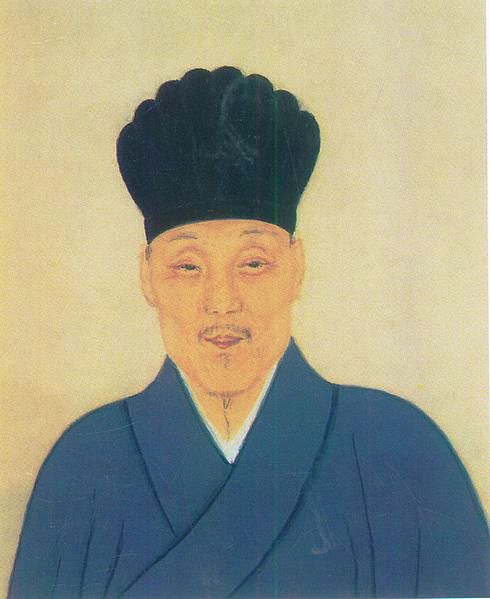

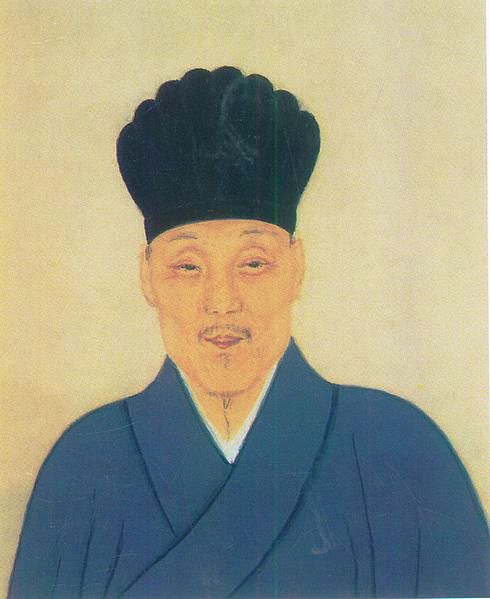

Left to right: Zheng

Zhilong (father), Koxinga (son), Zheng Jing

(grandson), and Zheng Keshuang (great-grandson)

(Source: Wikimedia Commons ZZ, K, ZJ, ZK)

Change is inevitable. From the

time we are born until the day we die, we

are changing. The catalysts of change may

be external or internal, and the result

may be good or bad. Such is the cycle of

life. In adolescence, we test boundaries.

We prepare to change from a child to an

adult. We adopt some behaviors and discard

others, depending on how others react,

what we learn, and how we feel.

As time passes, piracy changes. It is also

cyclical. Philip

Gosse, a physician and naturalist

with an avid interest in pirates,

describes this cycle in The History of

Piracy.

First a few individuals from

amongst the inhabitants of the poorer

coastal lands would band together in

isolated groups owning one or but a

very few vessels apiece and attack

only the weakest of merchantmen. They

possessed the status of outlaws whom

every law abiding man was willing and

eager to kill at sight. Next would

come the period of organization, when

the big pirates either swallowed up

the little pirates or drove them out

of business. These great organizations

moved on such a scale that no group of

trading ships, even the most heavily

armed, was safe from their attack. . .

.

Then came

the stage when the pirate

organization, having virtually reached

the status of an independent state,

was in a position to make a mutually

useful alliance with another state

against its enemies. What had been

piracy then for a time became war, and

in that war the vessels of both sides

were pirates to the other . . ..

In the end

the victory of one side would as a

rule break up the naval organization

of the other . . .. The component

parts of the defeated side would be

again reduced to the position of

outlaw bands, until the victorious

power was strong enough to send them

scurrying back once more to the status

of furtive footpads of the sea whence

they had arisen. (1-2)

Sound a bit

familiar? Gosse could have been describing

the Zheng clan’s rise to power. When

Koxinga died, they were on the cusp of

achieving “the status of an independent

state.” Zheng Zhilong’s success bred

legitimacy. Koxinga’s seizure of Taiwan

from the Dutch created the seed from which

an “independent state” might rise. His

son, Zheng Jing, would nurture that

genesis into near reality . . . although

not many thought him capable of doing so

after his father’s death.

Koxinga and his wife, Dong

Cuiying, welcomed their first son

into the world in 1642. They named him

Zheng Shifan (Model for the World),

although during his childhood, he was

usually called Jin-She (Bright Prospect

for the House). He tended to follow the

beat of his own drummer rather than

heeding his parents. He did so in ways

that suggested that he had little

backbone. He tended to follow his

emotions, which apparently appealed to

women, especially those who were older. He

also liked to drink, sometimes to excess. Koxinga and his wife, Dong

Cuiying, welcomed their first son

into the world in 1642. They named him

Zheng Shifan (Model for the World),

although during his childhood, he was

usually called Jin-She (Bright Prospect

for the House). He tended to follow the

beat of his own drummer rather than

heeding his parents. He did so in ways

that suggested that he had little

backbone. He tended to follow his

emotions, which apparently appealed to

women, especially those who were older. He

also liked to drink, sometimes to excess.

Shortly before his death, Koxinga

discovered that Zheng Jing was having a

fling with his younger siblings’ wet nurse

(Lady Chen). This affair resulted in the

birth of his first grandson, Zheng Kezang.

Koxinga went ballistic. He ordered Zheng

Jing’s execution. That did not happen,

perhaps because of Koxinga’s untimely

passing at the age of thirty-eight or

because two men, granduncle Zheng Tai and

longtime Zheng associate Hong Xu,

safeguarded him in Fujian.

Now that Koxinga was dead, who was to

become the next head of the family

business and rule Taiwan? Zheng Jing was

the obvious choice as eldest son, but

rumors said that Koxinga had sworn before

witnesses that he wanted his second son to

rule instead. The Taiwan waiji

says Koxinga’s choice was his younger

brother, Zheng Shixi, not his second son.

There were other family members who felt

they had stronger claims to succeed

Koxinga, especially given the rebellious

and wayward behavior of Zheng Jing, who

believed he was the rightful heir.

The first of these family members was

Zheng Tai, Koxinga’s uncle. While his

nephew was out fighting for the Ming

emperor, Zheng Tai oversaw the running of

the family business. Father Victorio

Riccio, a Dominican missionary from the

Philippines, said Zheng Tai “occupied the

primary and almost absolute post of

government since Cuesing’s (Koxinga’s)

death.” (Blussé, 230)

What was evident was that relationships

within the Zheng clan were not as smoothly

woven as the threads of their red silk

banner. These filaments were snapping and

discord was inevitable. Perhaps this was

why Zheng Jing took stock of his life and

found it wanting. Whatever catalyst made

him switch paths from rebellious

adolescent to a more rational adult, this

happened. As had occurred with his father

and grandfather, it was a moment when he

lacked sufficient resources to openly take

on his granduncle. Subtler means were

needed. First, he would watch and learn.

While Zheng Tai controlled the family’s

mainland holdings, the man who wielded the

power on Taiwan was Ma Xin, Koxinga’s

second-in-command. The two men did not

agree and the fissure dividing them only

widened when the Qing invited Zheng Tai to

discuss peace. He was open to this, even

though the olive branch being offered was

more severe than in the past. First, the

Zheng must leave all their bases in China.

Second, the men had to shave the front of

their heads

and wear what remained of their hair in a

long

braid down their back just as the

Manchu did. Only then would it be possible

to receive a high-ranking position and/or

special privileges.

_(14580605068).jpg)

Samples of Manchu queues

from Adolf Rosenberg's and Eduard

Heyck's Geschichte des Kostüms,

1905

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

Zheng Tai didn’t bother to consult with

his grandnephew or Ma Xin. He and the

other Zheng commanders in Xiamen would

agree. To show his seriousness in

accepting these conditions, he turned over

a few Zheng seals; in return, the Qing

would name him lawful head of the Zheng

organization. When Zheng Jing learned of

this, he was powerless to intervene and

went with the flow. Ma Xin, however,

severed connections between the island and

Xiamen and announced that Taiwan would now

institute its own government. There was

just one minor problem: the island had a

ruler named Zheng Xi. He might be just a

figurehead, but he was the tenth brother

of Koxinga and was in collusion with Zheng

Tai.

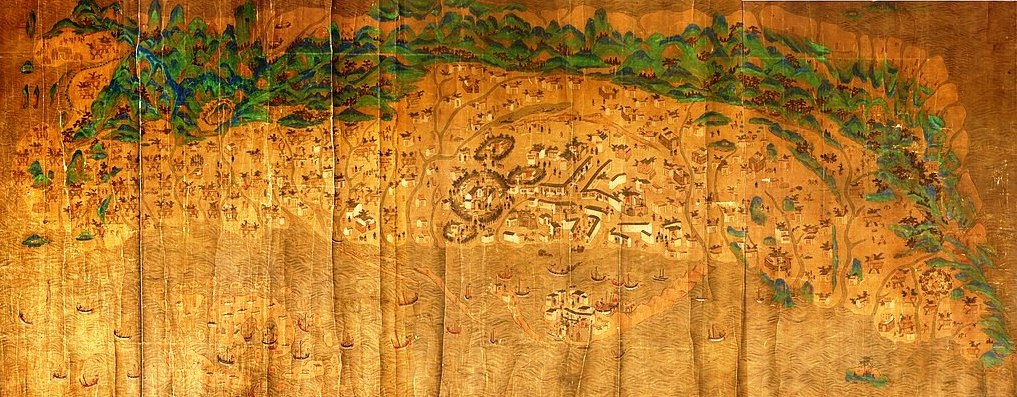

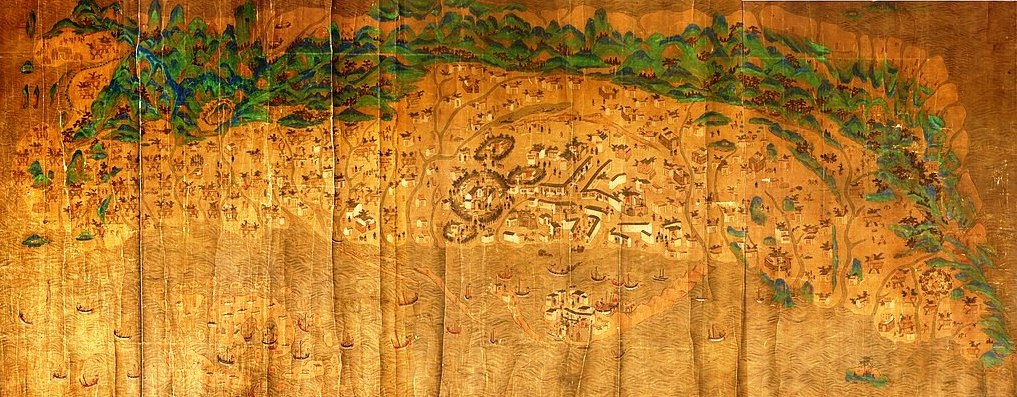

Scroll painting of

Taiwan during Kangxi era, 1684-1722 by

unknown artist

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

Zheng Xi, with the assistance of two

generals, decided it was time to terminate

Ma Xin. Once that man was out of the way,

another problem cropped up; they no longer

had any need of Zheng Jing. As they

determined how best to get rid of him and

what might be a plausible reason for doing

so, Zheng Tai found himself in trouble

because Ma Xin was dead. To placate other

members of the extended family, Zheng Tai

reevaluated his submission plans to the

Qing.

One commander in Xiamen was troubled by

Zheng Tai’s maneuverings without

consulting anyone. Hong Xu had been with

the family for more than thirty years; he

had worked alongside Zheng Zhilong in the

early days. Now Hong Xu decided it was

better to back the grandson and provided

Zheng Jing with the ships and soldiers he

needed to gain control over the family

enterprises. First objective: free Taiwan

of anyone colluding with his granduncle.

Once those men ceased to exist, the

remaining officers on the island

acknowledged that Zheng Jing was the

rightful heir to the Zheng enterprises.

During this first visit to Taiwan, Zheng

Jing unearthed correspondence between the

colluders and Zheng Tai. One letter,

written by Zheng Tai, said that if Zheng

Jing tried to gain control of the island,

Zheng Xi should make certain their

grandnephew died. If Zheng Jing wanted to

live a long and happy life, he had to deal

with his rival once and for all. Although

he and his men returned to Xiamen toward

the end of January 1663, it was not the

right time to confront Zheng Tai.

In July, there was to be a family

gathering and Zheng Tai accepted his

invitation. Father Riccio recorded what

happened.

[T]he son of the deceased

Cuesing [Koxinga] . . . during a

banquet treacherously arrested the

senior mandarin, Chuye [Zheng Tai],

the most powerful and richest man

there was in Imperial China. . . .

Chuye therefore hanged himself in his

cell the following day, grieved and

enraged at being mocked by a brigand,

and depressed over his ill fortune.

The land and the seas fell into chaos

at this tragic news because Chuye was

loved by all. (Blussé, 231-232)

Another

account, written by a Dutch official in

1665, chronicled what he had seen and

heard. (In this version of events, he

referred to Zheng Jing as “Kimtsia” and

Zheng Tai as “Sauja.” Formosa was Taiwan.)

Kimtsia saw that the hour of

his revenge had come and during the

banquet produced the letter and showed

it to Sauja, asking him if he was

familiar with it and had written it.

Sauja did not flinch and answered that

he had. He told him the motives that

had induced him to write it.

Thereupon

Kimtsia had his men seize the aged

man, had him thrown into prison and

strangled with a cord. A trusted

servant of Sauja who was present

managed to escape in the commotion . .

. carrying the sad news of this murder

to . . . Sauja’s brother. (Blussé,

234)

Many family members,

including the brother, and those who had

supported Zheng Tai decided their chances

of survival were better if they submitted

to the Qing rather than Zheng Jing. Zheng

Tai’s brother took with him “180 junks,

and over ten thousand soldiers.” (Hang,

150) The Qing couldn’t ask for a better

gift. The time had come to seize control

of Xiamen and Jinmen, two Zheng

strongholds. They also formed an alliance

with the Vereenigde Oostindische

Compagnie (VOC, or Dutch East India

Company), which had suffered such

humiliation at the hands of Koxinga. Many family members,

including the brother, and those who had

supported Zheng Tai decided their chances

of survival were better if they submitted

to the Qing rather than Zheng Jing. Zheng

Tai’s brother took with him “180 junks,

and over ten thousand soldiers.” (Hang,

150) The Qing couldn’t ask for a better

gift. The time had come to seize control

of Xiamen and Jinmen, two Zheng

strongholds. They also formed an alliance

with the Vereenigde Oostindische

Compagnie (VOC, or Dutch East India

Company), which had suffered such

humiliation at the hands of Koxinga.

On 19 November, the allies launched their

offensive. The combined fleet pitted

seventeen Dutch ships and 500 Qing junks

against Zheng Jing’s 400 vessels. Although

his men slew the Qing commander, there was

little he could do against 400 Dutch guns

and troops exceeding 2,500. This presented

Zheng Jing with two options: submit and

conform, or flee and live in exile

forever. Zheng Tai, with what remained of

his ships (at most fifty) and 4,000

officers and men as well as kindred of the

Ming imperial family, opted for exile and

left their homeland in April 1664.

Resources on Taiwan were limited; during

the siege against the Dutch, Koxinga had

run into trouble feeding the 25,000

soldiers already occupying the island. Nor

were they the only ones living there;

aborigines were present and they weren’t

particularly welcoming. Unlike his father,

who liked to oversee everything, Zheng

Jing preferred to seek advice. He

established a council of advisors, led by

his friend Chen Yonghua. Together, they

implemented policies, some of which

originated with Koxinga, to create a

viable agrarian system that, in turn,

resulted in some manufacturing that

allowed the island to become self-reliant

to a limited degree.

Next, Zheng Jing focused his attention on

reviving Zheng operations. Illicit trading

centers were established on unoccupied

islands. He bribed Qing officers and

officials, which allowed him access to

luxuries like silk. These items, along

with sugar and deerskins from Taiwan, were

then traded in Japan. Once the Zheng

business flourished once again, he was

able to branch further afield and trade

with foreigners.

He also developed

infrastructure and built temples and

shrines. Schools that promoted the values

of Confucius opened. Teachers went out to

work with the aborigines, instructing them

on better ways to farm and providing them

with the necessary implements and animals.

At the same time, he downplayed symbols

related to the Ming dynasty. He also

placed restrictions on members of the

gentry with strong ties to the old ways

who saw him as weak and ineffective. He also developed

infrastructure and built temples and

shrines. Schools that promoted the values

of Confucius opened. Teachers went out to

work with the aborigines, instructing them

on better ways to farm and providing them

with the necessary implements and animals.

At the same time, he downplayed symbols

related to the Ming dynasty. He also

placed restrictions on members of the

gentry with strong ties to the old ways

who saw him as weak and ineffective.

Like his father, Zheng Jing wrote poetry.

One poem, “Ti Dongning shengjing,”

described Taiwan and his desire to

preserve some traditions.

I have established a court,

and settled a capital, east of the

great sea,

A myriad

mountains and a plethora of valleys

are in the distance, crossing the sky.

Scented

forests rise high up into the clouds,

Green

waters flow along to gather in emerald

pools.

On both

banks fires are lit to welcome the

rising sun,

Across the

river the oars of the fishermen dip

against the dawn breeze.

In the past

I studied the words of the sage about

dealing with trouble.

The caps

and gowns of Han states have remained

the same since antiquity.

(Milburn, 67)

In another

poem, he shared his thoughts on the Manchu

invasion. He was two years old when the

Ming dynasty fell, and the upheaval that

followed impacted his life.

A foul and rank stench fills

the Central Plains,

The trees

in our forests provide nests for

foreign birds.

The Son of

Heaven has fled in a cloud of dust;

Everyone

complains of his minsters’ crimes.

(How right is this

criticism!)

Strong

knights cherish [dreams of] bravery

and heroism,

Their loyal

hearts are fixed on a single goal.

The banners

of these righteous warriors can be

seen across the land,

In the

endless parade, they cover the sun.

Those who

suffer in vain are the common folk,

For the

plans that are made are indeed not the

best.

One day,

the barbarian horsemen arrive;

Everyone

betrays [the Ming] for their own

personal benefit.

I am today

raising a royal army,

I will

punish the guilty – justice will be

done for the people.

I am

training up ferocious soldiers,

Building up

their strength on this eastern island.

I have been

hoping that the Green Phoenix will

arrive;

But even

after all these years, it still has

not appeared.

(Milburn,

73-74) (see notes 1, 2)

Despite his

dislike of the Qing, Zheng Jing understood

he needed them to recognize his government

on Taiwan as being legitimate. The one

sticking point in these negotiations, as

always, involved the Qing’s insistence on

adoption of their hairstyle. After two

years with no compromise found, each side

went back to their own corners. The Qing

did, however, become more tolerant of

Zheng presence on the island and upon the

seas.

During this time, Japan continued to send

tribute ships to the Qing to keep trade

open between the two countries. In 1670, a

Zheng junk seized one of these vessels and

its crew was slain. Two years later, when

a Zheng ship put in at Nagasaki, officials

seized its cargo. When Zheng Jing learned

of this, he banned all Japanese vessels

from docking in Taiwan. A shipwrecked

Japanese sailor was arrested and forced to

live and work for a peasant. Since trade

relations between Japan and the Zheng went

back at least to his grandfather’s

days, some saw this as counterproductive,

even risky. His interpretation was another

indicator in the stage of the piracy cycle

that Zheng Jing had achieved. His actions

“expressed his readiness to defend his

subjects from foreign rulers’ mistreatment

and unjust seizure of their property, to

the point of foregoing the lucrative

profits from trade.” (Hang, Bridging, 245)

Another indication of this stage involved

Zheng trading partners. He wanted Taiwan

to become a major player and act as a

gateway for international trade. No longer

would they rely just on goods from China

and Japan. They would trade with the

English, the Philippines, and other

countries of Southeast Asia.

In the early days of the

Qing dynasty, the emperor had given three

Ming defectors control of three regions

and, over the years, these feudal lords

pretty much had free reign in how they

ruled. The problem was that they were

becoming too powerful and the Kangxi

emperor wanted to curtail their power.

They did not take kindly to such

intervention and in 1673, rose up against

the emperor in what became known as the

Revolt of the Three Feudatories. One of

these feudal lords was Wu

Sangui, with whom Zheng Jing had

corresponded three years earlier. In the early days of the

Qing dynasty, the emperor had given three

Ming defectors control of three regions

and, over the years, these feudal lords

pretty much had free reign in how they

ruled. The problem was that they were

becoming too powerful and the Kangxi

emperor wanted to curtail their power.

They did not take kindly to such

intervention and in 1673, rose up against

the emperor in what became known as the

Revolt of the Three Feudatories. One of

these feudal lords was Wu

Sangui, with whom Zheng Jing had

corresponded three years earlier.

Every time I read Your

Highness’s letters, proclamations, and

drafts, I never fail to clap my hands

and sigh at the intensity of your

loyalty and filial piety, and am often

moved to tears afterward. Looking out

across the Four Seas, we all place

[hope] in Your Highness. During your

spare time outside of administration

and military affairs, are you familiar

with this solitary minister beyond the

pale? . . . Although my humble country

is small, I have a thousand war junks

and ten thousand warriors only for

Your Highness to use. I await your

virtuous reply from afar. (Hang, Conflict,

190)

It wasn’t that

Zheng Jing was eager to fight the Qing,

but he thought if he allied with Wu Sangui

and they were successful, then Wu Sangui

could grant him the legitimacy that he

wanted for Taiwan. Although his offer was

declined then, Wu Sangui and the other two

feudal lords accepted it in 1674, and

Zheng Jing returned to Fujian and

Guangdong. He composed a poem that

explained why he and the feudal lords

fought the Qing.

Floating away to campaign in

the west, riding on a battle-ship,

I sing

loudly when the oars strike as we

cross the waters.

The proper

destiny of the country will be

restored today,

The evil

influences of the barbarian caitiffs

will now be extirpated.

The common

people shout with joy at the

restoration of the Han house,

Exiled

ministers are delighted as they get to

gaze upon this sacred land.

After ten

years of training and preparation, now

is the time to act,

How could a

valiant knight refuse to cross the

seas this autumn?

(Grand and proud)

(Milburn,

80-81)

Map of the Revolt of the

Three Feudatories by SY, 2017

(Yellow arrows denote Qing campaigns)

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

His successes between 1675 and 1680

resulted in former Zheng adherents

rethinking their submissions to the Qing

and coming back into the fold. Eventually,

a problem developed. He was too far from

his base in Taiwan, which could not

provide him with needed supplies. In the

end, he turned to a piratical tactic:

plundering.

The Kangxi

emperor and his army would not

surrender. Slowly, the tide turned and the

three feudal lords found themselves in

dire straits. Two surrendered. Dysentery

claimed Wu Sangui in 1680. Zheng Jing and

his men returned to Taiwan. Unfortunately,

many of those who were closest to him,

including his friend Chen Yonghua, died

shortly thereafter. Devastated by the

losses of these men whose counsel he so

valued, Zheng Jing reverted to his old

ways. He drank too much and spent much of

his time with women. These overindulgences

led to his death the following year. He

was only thirty-nine, a year older than

Koxinga was when he died. The Kangxi

emperor and his army would not

surrender. Slowly, the tide turned and the

three feudal lords found themselves in

dire straits. Two surrendered. Dysentery

claimed Wu Sangui in 1680. Zheng Jing and

his men returned to Taiwan. Unfortunately,

many of those who were closest to him,

including his friend Chen Yonghua, died

shortly thereafter. Devastated by the

losses of these men whose counsel he so

valued, Zheng Jing reverted to his old

ways. He drank too much and spent much of

his time with women. These overindulgences

led to his death the following year. He

was only thirty-nine, a year older than

Koxinga was when he died.

Zheng Jing’s eldest son, Zheng Kecang,

succeeded him, but Koxinga’s wife, Dong

Cuiying, loathed this grandson because she

considered him of low birth since his

mother had only been a wet nurse. She felt

Zheng Jing’s next oldest son was more

deserving to rule of Taiwan. Two days

after Zheng Jing’s death, she summoned

Zheng Kecang to her apartment and

strangled him.

Zheng Keshuang assumed the

throne. Since he was only eleven years

old, his eldest uncle served as regent. In

1683, the Kangxi emperor decided it was

time to put an end to the Zheng once and

for all. To that end, he appointed Shi

Lang to effect that goal. Shi Lang was a

creative general who often tried new

approaches to achieve what he desired and

he was quite successful in doing so. He

had also once served Koxinga,

until irreparable differences resulted in

Shi Lang’s defection. Now he intended to

wipe out the Zheng fleet and force Zheng

Keshuang to submit. Zheng Keshuang assumed the

throne. Since he was only eleven years

old, his eldest uncle served as regent. In

1683, the Kangxi emperor decided it was

time to put an end to the Zheng once and

for all. To that end, he appointed Shi

Lang to effect that goal. Shi Lang was a

creative general who often tried new

approaches to achieve what he desired and

he was quite successful in doing so. He

had also once served Koxinga,

until irreparable differences resulted in

Shi Lang’s defection. Now he intended to

wipe out the Zheng fleet and force Zheng

Keshuang to submit.

He achieved both goals and those who

survived were forced to discard their

weapons and move far inland in China. Some

warriors, adept at their jobs, were

permitted to retain their weapons and

fight, but they did so in Manchuria

against the Russians. Other followers

resumed their former lives, returning to

the first stage in the piracy cycle, this

time in the Gulf of Tonkin.

Zheng Keshuang cut his hair and dressed as

the Qing did. He lived in Beijing, where

he was named Duke Who Quells the Seas, one

of several honorary titles he received. In

1684, the Kangxi emperor lifted the last

sea bans and even permitted foreigners to

come into Chinese ports to trade.

Piracy continued to be a pursuit of those

who had allied with the Zheng. In the

early years of the nineteenth century,

another Zheng would rise to the forefront

of Chinese history. (see note 3) He

and his

wife would establish a pirate

confederation that rivaled the imperial

navy and controlled the waters around the

same coast as Zheng Zhilong and his

family.

Notes:

1. The Green Phoenix was

the rightful emperor.

2. The boldfaced lines within

parentheses are comments that appeared in

the earliest published book containing the

poems. Most likely, Zheng Jing oversaw

this edition; he may have penned these

(comments) himself.

3. Zheng Yi was the

son of Zheng Liaching, whose

great-grandfather, Zheng Qián (Cheng

Chien), joined Koxing soon after moving to

Fujian in 1641. He served as an officer in

Koxinga's army. Although he eventually

returned to farming, some of his offspring

and their descendants chose piracy as

their calling.

Resources:

Anderson, John L. "Piracy and

World History: An Economic Perspective

on Maritime Predation," Bandits at

Sea: A Pirates Reader edited by C.

R. Pennell. New York University, 2001,

82-106.

Andrade, Tonio, and Xing Hang. “The East

Asian Maritime Realm in Global History,

1500-1700,” Sea Rovers, Silver, and

Samurai: Maritime East Asia in Global

History, 1550-1700. University of

Hawai'i, 2019, 1-27.

Antony,

Robert J. Like Froth Floating on the

Sea: The World of Pirates and

Seafarers in Late Imperial South China.

Institute of East Asian Studies,

University of California, 2003.

Blussé, Leonard. “Shame and Scandal in

the Family: Dutch Eavesdropping in the

Zheng Lineage,” Sea Rovers, Silver,

and Samurai: Maritime East Asia in

Global History, 1550-1700.

University of Hawai’i, 2019, 226-237.

Clements, Jonathan. Coxinga and the

Fall of the Ming Dynasty. Sutton,

2005.

Emmer, Pieter C., and Joseph J. L.

Gommans. The Dutch Overseas Empire,

1600-1800 translated by Marilyn

Hedges. Cambridge University, 2021.

Gosse, Philip. The History of Piracy.

Rio Grande Press, 1995.

Hang Xing. “Bridging the Bipolar: Zheng

Jing’s Decade on Taiwan, 1663-1673,” Sea

Rovers, Silver, and Samurai: Maritime

East Asia in Global History, 1550-1700.

University of Hawai’i, 2019, 238-259.

Hang Xing. Conflict and Commerce in

Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family

and the Shaping of the Modern World,

c. 1620-1720. Cambridge

University, 2017.

Hang Xing. “The Contradictions of

Legacy: Reimaging the Zheng Family in

the People’s Republic of China,” Imperial

China 34:2 (December 2013), 1-27.

Konstam, Angus. Piracy: The Complete

History. Osprey, 2008.

Milburn, Olivia. “Representations

of History in the Poetry of Zheng Jing,”

Ming Qing Yanjiu 21 (2017),

58-92.

Murray, Dian H. Pirates of the South

China Coast 1790-1810. Stanford

University, 1987.

Xu Ke.

“Piracy, Seaborne Trade and the

Rivalries of Foreign Sea Powers in East

and Southeast Asia, 1511 to 1839: A

Chinese Perspective” in Piracy,

Maritime Terrorism and Securing the

Malacca Straits edited by Graham

Gerard Ong-Webb. International Institute

for Asian Studies and the Institute of

Southeast Asian Studies, 2006.

Copyright ©2023 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |

Koxinga and his wife,

Koxinga and his wife, _(14580605068).jpg)

Many family members,

including the brother, and those who had

supported Zheng Tai decided their chances

of survival were better if they submitted

to the Qing rather than Zheng Jing. Zheng

Tai’s brother took with him “180 junks,

and over ten thousand soldiers.” (Hang,

150) The Qing couldn’t ask for a better

gift. The time had come to seize control

of Xiamen and Jinmen, two Zheng

strongholds. They also formed an alliance

with the Vereenigde Oostindische

Compagnie (VOC, or Dutch East India

Company), which had suffered such

humiliation at the hands of Koxinga.

Many family members,

including the brother, and those who had

supported Zheng Tai decided their chances

of survival were better if they submitted

to the Qing rather than Zheng Jing. Zheng

Tai’s brother took with him “180 junks,

and over ten thousand soldiers.” (Hang,

150) The Qing couldn’t ask for a better

gift. The time had come to seize control

of Xiamen and Jinmen, two Zheng

strongholds. They also formed an alliance

with the Vereenigde Oostindische

Compagnie (VOC, or Dutch East India

Company), which had suffered such

humiliation at the hands of Koxinga. In the early days of the

Qing dynasty, the emperor had given three

Ming defectors control of three regions

and, over the years, these feudal lords

pretty much had free reign in how they

ruled. The problem was that they were

becoming too powerful and the Kangxi

emperor wanted to curtail their power.

They did not take kindly to such

intervention and in 1673, rose up against

the emperor in what became known as the

Revolt of the Three Feudatories. One of

these feudal lords was

In the early days of the

Qing dynasty, the emperor had given three

Ming defectors control of three regions

and, over the years, these feudal lords

pretty much had free reign in how they

ruled. The problem was that they were

becoming too powerful and the Kangxi

emperor wanted to curtail their power.

They did not take kindly to such

intervention and in 1673, rose up against

the emperor in what became known as the

Revolt of the Three Feudatories. One of

these feudal lords was

The

The  Zheng Keshuang assumed the

throne. Since he was only eleven years

old, his eldest uncle served as regent. In

1683, the Kangxi emperor decided it was

time to put an end to the Zheng once and

for all. To that end, he appointed Shi

Lang to effect that goal. Shi Lang was a

creative general who often tried new

approaches to achieve what he desired and

he was quite successful in doing so. He

had also once served

Zheng Keshuang assumed the

throne. Since he was only eleven years

old, his eldest uncle served as regent. In

1683, the Kangxi emperor decided it was

time to put an end to the Zheng once and

for all. To that end, he appointed Shi

Lang to effect that goal. Shi Lang was a

creative general who often tried new

approaches to achieve what he desired and

he was quite successful in doing so. He

had also once served