Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Books for Adults ~ Law: Crime, Punishment, & Pirate

Hunting

Convicts in the Colonies: Transportation Tales

from Britain to Australia

by Lucy Williams

Pen & Sword, 2018, ISBN 978-1-52671-837-2, US

$39.95 / UK £19.99

review by Irwin Bryan

Here

is a book that looks deeply into the lives of some

of the convicts who are sentenced in court to be

transported to Botany Bay, the first colony

established in New South Wales, Australia. Through

their lives we learn about criminal justice and

punishment in Great Britain. We delve into the

places where convicts are kept, conditions on the

ships that transport them across the oceans, and

the dangers they face along the way. Readers are

told about life in the different colonies that are

eventually formed and how free convicts live out

their years as members of a developing country.

Our guide is an author who works on a major

project to create individual histories for as many

as possible of the 168,000 people transported to

Australia between 1787 and 1868. In a lengthy

introduction, she explains her background as “a

social historian of women, crime, and deviance,”

(xii) and that stories of female convicts are used

wherever possible. An added caution reminds

readers that any implied compassion expressed for

these convicts does not mean the victims of their

crimes should be forgotten.

The opening chapter takes a close look at the

criminal justice system. This includes information

about trials, sentencing, and waiting for years

before being shipped out of the country. Male

criminals, including juveniles, are mostly kept in

hulks (old wooden warships with the masts and

cannons removed and modified to house prisoners in

one room below the upper deck). The longer a

prisoner is kept on a hulk the more their health

deteriorates before the long voyage to Australia.

Women are mostly kept in the same gaol they are in

before trial and transported with other women onto

ships just for women convicts.

Next, the dangers faced on the voyage are

explored. These include rampant disease and death

from the conditions aboard and a diet that doesn’t

include fresh food or vegetables for a prolonged

time. Convicts are lost in several shipwrecks and

even a mutiny.

The stories of three convict women are told. One

involves a lucky escape with several male convicts

in an open boat. The second woman becomes a

wealthy businesswoman. The third has twenty-one

children and thousands of descendants who help to

populate the country.

There are three different

colonies where convicts are shipped:

Botany Bay (relocated to Sydney), Van

Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), and Western

Australia (Freemantle). A chapter is

devoted to each colony.

Conclusions are

then presented by the author. These include the

costs and benefits Australia experiences during

the eighty years of transportation and for at

least another seventy years when the last convict

passes away. One appendix features the texts of

quoted letters showing the original spelling and

lack of punctuation. Another appendix lists many

resources that can be used to trace transported

convicts and their stories. There is a section for

suggested reading and an index as well. The inset

has twenty-four, mostly color, images of the

places convicts are housed and some of the

convicts mentioned in this book.

Anyone with an interest in the development of

Australia or the transportation of convicts can

learn from this text and enjoy the up-close look

at the individuals whose own words are used to

describe what they see and experience.

Review Copyright ©2019 Irwin Bryan

Enemies of all Humankind: Fictions

of Legitimate Violence

by Sonja Schillings

Dartmouth College, 2017, ISBN 978-1-5126-0016-2,

US $40.00

Also available in other formats

The concept of hostis humani

generis dates back to Cicero, when he

uses this phrase to describe pirates as the

enemies of all humankind. What Schilling does

in this latest volume in Darmouth’s Re-mapping

the Transnational series is to show the

evolution of this concept and the application

and use of legitimate violence to defeat these

enemies from when it is first applied to

pirates up to today’s terrorists, particularly

as it pertains to the growth and maturation of

America.

The author divides the book into four parts

and uses both fiction and non-fiction to

showcase her argument.

Introduction

Part I. The Emperor and the

Pirate: Legitimate Violence as a Modern

Dilemma

1. Augustine of Hippo: The

City of God

2.

Charles Johnson: A General History of

the Pyrates

3.

Charles Ellms: The Pirates’ Own Book

Part

II. Race, Space, and the Formation of the Hostis

Humani Generis Constellation

4. Piratae and Praedones:

The Racialization of Hostis Humani Generis

5.

John Locke, William Blackstone, and the

Invader in the State of Nature

6.

Hostis Humani Generis and the

American Historical Novel: James Fenimore

Cooper’s The Deerslayer

Part

III. The American Civilization Thesis:

Internalizing the Other

7. The Frontier Thesis as a

Third Model of Civilization

8.

The Democratic Frontiersman and the

Totalitarian Leviathan

9.

Free Agency and the Pure Woman Paradox

10.

The Foundational Pirata in Richard

Wright’s Native Son

Part

IV. “It Is Underneath Us”: The Planetary

Zone in between as an American Dilemma

11. The Institutional Frontier:

A New Type of Criminal

12.

Who Is Innocent? The Later Cold War Years

13.

Moshin Hamid’s The Reluctant

Fundamentalist and the War on Terror

Conclusion

The

book also includes a list of abbreviations,

endnotes, an extensive list of the works

cited, and an index.

Victims of violence rarely control what

happens to them, but over time, especially in

Western tradition, the idea of legitimate

violence – the use of force to subdue

aggression – has been employed to defend

innocent targets. What Schilling does in this

book is show how the theory of legitimate

violence has developed and evolved over time;

how discussions on hostis humani generis

are and have been maintained throughout the

history of the United States; and how the

parameters of both have changed over the

centuries to warrant the protection of new

victims.

Who are the perpetrators who fall under the

umbrella of hostis humani generis and

against whom legitimate violence is permitted?

The initial enemies are pirates, but the

passage of time has also permitted slavers,

torturers, and terrorists, as well as any

group that commits crimes against humanity, to

be so labeled. While the concept of hostis

humani generis is actually a legal

fiction, its close association to piracy often

leads scholars to believe they must first

understand the pirate in order to comprehend

why such people warrant the labeling of

"enemies of all humankind." Schilling

disagrees with this belief for two reasons.

First, the definition of “pirate” changes over

time, and that flexibility introduces

inconsistency into such an analysis. Secondly,

other perpetrators of violence replace pirates

as such enemies. This is why she refers to hostis

humani generis as a constellation, a

group of people related by their violent acts

against innocent people.

The first two parts of this study are of

particular interest to those who study and

read about pirates, although Barbary corsairs,

Somali pirates, and comparisons to the sample

texts in chapters two and three are mentioned

elsewhere. In the first section, Schilling

discusses the origin of hostis humani

generis and Saint Augustine’s broadening

of the concept. This constellation finally

comes into its own in the 16th century as

European countries extended their borders to

include territories in the New World. The

second section focuses more on the law and

invaders, such as the renegadoes from

the Barbary States.

While many readers will clearly understand

that some texts that are used here to support

her argument fall definitively into either

non-fiction or fiction, Schilling doesn’t

clarify that Johnson’s A General History

of the Pyrates and Ellms’s A

Pirates’ Own Book are actually a mix of

both. These two authors interweave facts with

imagination to better capture their readers’

interest. Overall, Enemies of All

Humankind is a thought-provoking,

scholarly examination that will stimulate

interesting discussion on a topic that has

particular relevance not only to the study of

the past but also to global events unfolding

every day in our own world.

Review Copyright ©2017 Cindy Vallar

Murder & Mayhem

in Essex County

Murder & Mayhem

in Essex County

by Robert Wilhelm

The History Press, 2011, ISBN

978-1-60949-400-1, US $19.99

The

stories in this book take place in Essex

County, Massachusetts. They are a mix of

truth and legend, but the author allows the

reader to draw his/her own conclusion about

each one. Wilhelm presents this collection

in a chronological sequence, from the

earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay

Colony to 1900. The introduction sets the

scene and provides historical background the

general reader may not know. Each chapter

includes black-&-white photographs of

people, artifacts, and places pertaining to

the subject matter.

The murders discussed within these pages

include Mary Sholy (1636), John Hoddy

(1637), Ruth Ames (1769), Captain Charles

Furbush (1795), Captain Joseph White (1830),

Charles Gilman (1877), Albert Swan (1885),

Carrie Andrews (1894), John Gallo (1897),

and George Bailey (1900). The culprits are

both male and female, from a variety of

backgrounds, and the victims range in age

from children to adults. The mayhem includes

accounts of witches, Indian captives, arson,

and pirates (Thomas Veal, John Philips, and

Rachel Wall).

If more than one version of the crime

exists, Wilhelm provides all of them. If a

primary document exists, he incorporates it

into the telling. All the chapters are

fascinating, but the one most pertinent to

us concerns the pirates of Essex County. I

am familiar with John Philips and Rachel

Wall, but Thomas Veal is new to me, and I

particularly like this chapter because these

aren’t rogues that appear often in other

volumes.

The only drawback concerns a handful of

illustrations that don’t fit the mood

instilled by this collection of slaughter

and villainy. They are too comic-like and

detract from the gritty, historic feel that

the crimes engender. Despite this objection,

readers interested in murder, mayhem, and

true crime will enjoy this journey to the

dark side.

Review Copyright ©2012 Cindy

Vallar

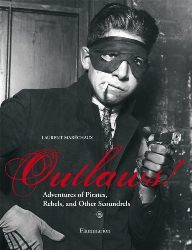

Outlaws! Adventures of

Pirates, Scoundrels, and Other Rebels

by Laurent Maréchaux

Flammarion, 2009, ISBN 978-2-0803-0107-9,

US $45.00 / Can $54.00 / UK £27.50 / EUR

€40.00

No

one is born an outlaw. They are made.

These are the individuals whom the

author showcases in this coffee-table

book. No matter into what

classification they fall, each lives

outside the law. Each suffers an

untimely death of a mother or father at

a young age or experiences a tragic

event that forever alters his or her outlook on

life and the world around them. Although

we know these men and women break the

law, they fascinate us. According to the

author, “We should not . . . rush to

judge the errant ways of these

idealistic vagabonds. They deserve our

recognition. Without them, the maps of

this world would be less colorful, our

taxes and rights would be less human,

democracy . . . would be lacking in

imagination, and our eternal quest for a

better world would be nothing but an

outmoded fancy.” (page 10)

Divided into six groupings, the book

introduces readers to the familiar and

the stranger, the distant and the near

past, the western and the eastern. Each

section begins with a short introduction

that makes the reader ponder the

rightness or wrongness of these

individuals’ actions and those of

society. Either a color or

black-&-white, full-page portrait of

the individual outlaw introduces us to

him or her. Other illustrations

accompany the text, which talks about

this person’s life and death over four

to six pages. The book concludes with

notes and a bibliography.

Of particular

interest to readers of Pirates and

Privateers is the section titled

“The Black Sail and the Call of the High

Seas.” The author begins with a quote

from Alexandre Exquemelin, the buccaneer

surgeon who writes The Buccaneers of

America:

Alive

today, dead tomorrow, what does it

matter whether we hoard or save. We

live for the day and not for the day

we may never live.

This perfect

quote neatly sums up the pirates’

philosophy. Few readers may be familiar

with the first outlaw showcased, Jehan

Ango, but one of the corsairs who sail

for this shipowner and privateer is Jean

Fleury, the first to capture a Spanish

treasure galleon. The other pirates

profiled are: the Barbarossas; Sir

Francis Drake; François l’Olonnais;

Bartholomew Roberts; Edward Teach; Anne

Bonny, Calico Jack Rackham, and Mary

Read; Olivier Mission, the Monk

Caraccioli, and Thomas Tew; and Ching

Shih. A page from Drake’s 1598 log is

reproduced, as are several period maps.

While an earlier profile discusses Robin

Hood as both fictional and real, the

same does not occur in the summary about

Olivier Mission, whom many historians

believe to be fictitious.

Another

person of interest to pirate enthusiasts

appears in the section “Desert Devils,”

for one of Renaud de Châtillon’s

occupations is that of pirate. His name,

like others, may not be familiar to

readers, but others will be: Henry David

Thoreau, Jesse James, Billy the Kid,

Calamity Jane, Richard Francis Burton,

Lawrence of Arabia, Bobby Sands, and

Bonnie and Clyde.

Outlaws!

is an intriguing book and even the cover

art taunts the reader to look inside.

This is a well-rounded, international

collection of those who live on the

fringes of society. Each account is

compelling and fascinating. The quotes

that begin each chapter are well chosen

and thought-provoking. The author

himself is something of a rebel so he

knows whereof he writes.

Perhaps the

quote that begins the “City Hoodlums and

Urban Gangs” section best clarifies the

outlaw and sums up this book:

Some

will turn me into a hero, but there

are no heroes in crime. There are

just men who . . . are marginal, and

who don’t respect laws because laws

are made for the rich and powerful.

– recorded testament of Jacque Mesrine

Quelch’s

Gold: Piracy, Greed, and Betrayal in

Colonial New England

Quelch’s

Gold: Piracy, Greed, and Betrayal in

Colonial New England

by Clifford Beal

Praeger, 2007, ISBN 978-0-275-99407-5,

US $44.95 / UK £25.95

In 1703, Charles,

a brigantine, mysteriously sets sail

from Marblehead, Massachusetts. She

returns ten months later, and her

captain and most of her crew find

themselves under arrest for piracy.

Within the pages of this book, Beal

explores the case of John Quelch and

the government officials involved in

his arrest and trial, for some

consider what happens to be “the

first case of judicial murder in

America."

Divided

into three sections, the book

explores the crime, pursuit,

punishment, and reward. The account

is absorbing and well-researched,

but at times, the author interrupts

the flow to provide important

information to help place the events

into their proper time and place.

Perhaps a different rendering may

have enabled readers to better

follow the story. Despite this, Beal

deftly weaves a tale of intrigue and

abuse by authorities to prosecute

Quelch for piracy.

Review Copyright

©2007 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |