| Cindy

Vallar

Author,

Columnist,

& Editor |

|

| Cindy

Vallar

Author,

Columnist,

& Editor |

|

|

|

|

|

Age of Sail Workshop

This workshop primarily examines wooden sailing ships and maritime trade from 1600 to 1850. The photographs are from my visits to Mystic Seaport in Connecticut; Cape Cod, the Mayflower II, and Salem Maritime National Historic Site in Massachusetts; and the Fells Point Maritime Museum in Maryland. This page serves as a companion to the lessons and materials provided during the workshop.

Ship Construction

Thomas Kemp, a shipbuilder in Fells Point, built the Baltimore privateer Patapsco during the War of 1812. This list details the principal purchases made in the building of the schooner. It also demonstrates the various artisans who were essential in a ship's construction.

Ships are built in shipyards, similar to this one at Mystic Seaport that preserves vessels of a bygone era. The Henry B. duPont Preservation Shipyard occupies the site of a 19th-century shipyard. Here you find a carpenter's shop, a paint shop, a ship's smithy, a sawmill, and a lumber shed where stacks of timber are seasoned and stored. The typical trees used in building ships include oak and pine. One vessel built here was Amistad, a replica of the Spanish schooner carrying slaves who mutinied. Today's Amistad has an educational mission that emphasizes history, leadership, and cooperation.

This museum display depicts a small section of the keel and frame of a ship's hull. Planks are laid across the ship's frame, which is akin to a person's spine and ribcage, on the inside and outside of the hull. What you see above would be below the water once the vessel is launched. The three pictures below show (a) the exterior of the hull, (b) the same view from the interior of the hull, and (c) a finished view of the interior hull.

View A

View B

View C

Nature was a wooden ship's enemy. Some dangers were always visible, such as a storm at sea like the one that killed Samuel Bellamy and most of the pirates aboard the Whydah. Others lurk where they couldn't be seen, such as this tiny creature -- the shipworm -- that ate the wood from the outside in and caused her to leak. Wooden ships that weren't regularly careened didn't last long. One example of this is William Kidd's Adventure Galley, which spent months at sea without having the proper maintenance to her hull. She leaked like a sieve and was eventually abandoned and burned.

The case above displays the tools of a sailmaker and rigger, while the one below showcases those of a ship's carpenter. These men were essential in the building of a wooden ship. A sailmaker, such as James Forten, measured the yards and masts then designed the sails to catch the wind that powered the ship. A rigger was responsible for the standing rigging that supported the masts and the running rigging for the sails. These men were mostly found on shore, although seamen aboard the ships could repair sails and rigging when necessary. The carpenter, on the other hand, could be found either in port or at sea, for he was an essential member of any ship's crew. He kept the ship afloat.

Ships used a variety of blocks (pulleys) for various tasks, such as stowing cargo or handling the sails. This is a trebel block, which would be used to hoist particularly heavy items like an anchor.

The Ship Herself -- Exterior

The center plank of this deck contains three hexagonal objects known as deck prisms or deck lights. Their purpose was to provide some illumination to the deck below, although it was minimal, being equivalent to a 30-watt bulb. One end was hexagonal and flat, while the other end was cone-shaped and pointed. Made of glass, deck lights first appear in the historical record in the 1800s. They may have existed prior to that time, but the experts I consulted were unable to say when they were first used.

Shipcarvers created the figureheads featured on vessels' bows. This particular one belonged to the Benjamin F. Packard, a square-rigged sailing ship of the late 19th century. For twenty-five years she sailed back and forth between New York and San Francisco via Cape Horn and also to Europe.

Ships had a variety of anchors. This is a bower anchor. A ring at the top, which was threaded through an eye, attached the anchor to its cable. The crosspiece, called a stock, has bands around it. The long, vertical bar is the shaft, at the end of which are the crown and two arms extending to either side. The large triangular pieces are called palms or flukes and each has a pointed tip known as a bill. Bower anchors, carried on either bow of the vessel, were the largest of the ship's anchors. The starboard bower was called the best bower, and the larboard bower, the small bower (even though it was usually the same size as the other one). This particular bower anchor probably came from a 74-gun ship of the line, possibly one of the Royal Navy vessels that blockaded Newport, Rhode Island.

During the Age of Sail, merchant vessels sometimes carried guns aboard just in case pirates or an enemy vessel approached. This particular one is on the Joseph Conrad, a schoolship located at Mystic Seaport. Also visible to the left rear of the gun is a skylight, which provides sunlight to the cabin below.

This companion way of the Charles W. Morgan provides access below. The wooden base is the hatch coaming, while the wooden hood over it is the companion. Unseen is the ladder to go belowdecks or to come above. This companion way is situated behind one of the masts.

Stern view

Side View

The Mayflower II is a replica of the ship that brought settlers to Plimoth Colony in 1620, although she originally participated in the wine trade, which was why she looks like she has a pot belly. Both pictures provide a good view of her poop deck, the highest aft deck on the ship. Her mainmast rises forty-four feet above the deck. On top of this is a twenty-four-foot topmast, and atop that is a fourteen-foot staff from which she flew the flag that designated her a merchant ship. In contrast, her foremast had a total height of fifty-nine feet above the deck and flew the St. George flag.

All ships carried boats that were used for various purposes. These two pictures show different views of the Mayflower II's boat, which had a single sail. The view on the left also shows the Mayflower II's forecastle, where the ship's cook prepared hot food for the seamen serving aboard her. Also visible at her bow is the bowsprit and the furled spritsail. A lookout would stand atop the yard (the horizontal spar) holding the sail.

The Ship Herself -- Rigging and Sails

The tools in this display case are used for navigation. Until the second half of the 18th century, seamen weren't able to determine longitude because a sea clock that accurately kept time hadn't yet been invented. Until the chronometer's invention, dead reckoning was used to compute a ship's longitude, but that computation was usually inaccurate. Latitude was the primary measurement used to figure out a ship's location. The most prominent piece above is the sextant, used to measure latitude. It was preceded by the cross-staff and the back staff or quadrant.

Left Markers Main Topsail

Mizzensail (Lateen)

Mizzen Bonnet

Main Bonnet Main Course Fore BonnetRight Markers Fore Topsail

Fore Course

Spritsail

The diagram above depicts the sails and rigging of the Mayflower II. A course is the lowest sail on a mast. A bonnet is a piece of canvas laced to the bottom of a sail to make it bigger. It was used in moderate weather. The left side shows the stern, while the right side shows the bow.

Two types of rigging exist on a ship. Standing rigging are the ropes that support the masts, while running rigging work the sails. Standing rigging, of which this is an example, was black. This particular picture shows a closeup of the ratlines and the shrouds. The shrouds are vertical ropes running from the mast to the side of the vessel. The ratlines are the horizontal ropes strung between the shrouds. These form the "ladder" seamen climbed to go aloft to tend the sails.

This picture shows an unfurled, square sail that hangs from a spar.

In contrast, the sails for this vessel are fore- and-aft ones. These parallel the ship, whereas a square sail extends across the vessel. The spars that hold a fore-and-aft sail are called gaffs, one end of which fits around the mast. Between the gaffs holding the top and bottom of the sail are mast hoops used to attach the luff (forward edge) of the sail to the mast. These slide up and down the mast as the sail is raised and lowered.

This picture shows seamen standing on footropes while furling a sail.

This view of the mainmast clearly shows the three yards that hold the sails. The highest is the upper main topsail yard. Below that is the lower main topsail yard. The bottom spar is the main yard.

Lookouts kept an eye out for land, another ship, or possible danger. They were often posted on the fore and mainmasts. Some stood on platforms called tops, while others stood on crosstrees. The upper left picture is a top on the Mayflower II. It resembles a bowl, whereas the one to the left is a flat top that was common on ships of later periods. The shot above right has hoops for the lookouts, who stood on the crosstrees. While the Mayflower's top resembles a crow's nest, this term didn't exist in the 17th century. It was first used by whalers in the 1800s.

The Ship Herself -- Interior

The Mayflower's gun deck was below the main deck. This was also where her passengers lived amid the guns. Although she had twelve gun ports, it's unlikely she carried that same number of guns. Four minions (a type of gun) were positioned on each side of the vessel, plus she carried a four-pound gun. The main deck provided locations for two sakers, and there were two more of these lighter and shorter guns located in the gunroom as stern chasers. The rest of her armament included "muskets, arms, pitchpots and shovels."

Ships of the 17th century didn't have a ship's wheel on the quarterdeck for steering her. Instead the helmsman was positioned in the steerage cabin. All he could see from the two openings ahead of him were the sails. Lookouts relayed needed information, while the navigator stood on the deck above and relayed instructions through a speaking tube. The helmsman steered the Mayflower using the pole in the center of this picture. This was the whipstaff, which was connected to the tiller that was connected to the rudder. The steerage cabin was located below the half deck aft of the main mast. The compartment in front of the whipstaff was the "bittacle," which housed the compass.

Directly behind the helmsman was a traverse board similar to this one. A ship's day began at noon and was divided into four-hour periods called watches. During each watch, a seaman recorded the ship's direction and speed on the traverse board by placing pegs in the appropriate holes. The compass showed the direction and the chip-log, a weighted board attached to a line, was used to determine the speed. At the end of the watch either the master or navigator recorded the information on the traverse board in the ship's log, then removed the pegs so the next watch could collect the data all over again.

These were the officers' quarters aboard the Mayflower. The picture to the left was probably the navigator's berth, for it was located on one side of the steerage cabin and the instrument atop the navigational chart was a cross-staff, used to measure the ship's latitude. The two pictures below are the berths in the stern cabin, where the ship's master and his chief officers lived during a voyage. This cabin was located below the poop deck aft of the mizzenmast. Aside from the steerage cabin, this was the only compartment with windows.

In contrast to the officers' cabins, the passengers aboard the Mayflower didn't have such luxuries. There was little privacy and the space was crammed with seventy to eighty people in one large area 'tween decks. The main deck was above, the hold below. Some passengers fashioned small cabins no bigger than a bed, while others stretched out on straw mattresses on the floor. In fair weather, they were permitted topside to breathe fresh air and take the sun. In rough seas, they stayed below with the hatches battened down, which meant someone on the main deck had to release them. Not only were the people quartered here, but so were the animals, which meant the air turned foul quickly.

The Mayflower's galley stove was located in the fo'c'sle (forecastle). A ship's cook was often a disabled seaman and being able to cook wasn't a requirement for the job. He was considered an idler, which meant he didn't have to stand watch. Idlers were the only members of the crew who could sleep through the night. The crew lived in the fo'c'sle, too, wherever they found room.

These pictures show a sampling of the provisions the Mayflower probably carried: salted beef, pork, and fish, dried peas, butter, cheese, and oatmeal. Fresh water turned foul, so beer and wine were the beverages served.

In contrast to the quarters aboard the Mayflower, this was the fo'c'sle of the Charles W. Morgan, where the crew lived and slept and the cook prepared their meals. Each man slept in his own bunk, which was usually six feet in length. An edged table with benches on either side was where they ate their meals.

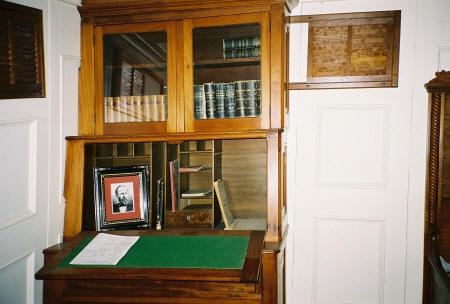

Accommodations aboard the Benjamin F. Packard were luxurious compared to those aboard the Mayflower. Below is the captain's berth and his desk, both of which were located in his stateroom at the stern of the vessel.

Seaports

Barrels came in a variety of sizes, and each had a different name. This one was called a "tun" and held 256 gallons. Others were called casks and hogsheads. These containers carried spirits, molasses, water, flour, potatoes, apples, crockery, and many other items. This particular tun carried liquid, for it was fashioned from a hardwood and banded together with iron rings. Barrels that didn't hold liquids lacked the iron rings. They were called "slack casks" and were made from softwoods.

An important business in any seaport was the ship chandlery. This store carried just about anything needed on a vessel. The chandler had to know the community in which he lived as well as the ships that put into port. He carried specialized equipment, such as those items needed in the fishing or whaling industry if those were the type of vessels he serviced on a regular basis. Typical stores included salted fish, beef, and pork, ship's biscuits (hardtack), molasses, potatoes, onions, spices, flour, rum, tobacco, blankets, pipes, knives, clothing, navigational instruments, lanterns, buoys, logbooks, inkstands, needles, beeswax, canvas, marine hardware, paint, and oil. These particular pictures are of the ship chandlery at Mystic Seaport, which showcases items of the 19th century.

From the spinning of raw fibers to the finished cordage used aboard ships, the ropewalk was an essential business to a seaport, particularly one that also built ships. The Plymouth Cordage Company Ropewalk was housed in a building that was 1,050 feet long. It produced rope as long as 100 fathoms (600 feet). The picture above was where the fibers were spun into yarn. The picture below showcases the rack containing the spools of yarn used to assemble the rope.

The yarns from these spools were inserted into this machine, which twisted the yarns together into a single strand using a moving "truck" that traversed the length of the ropewalk floor. Three or more of these strands were then twisted together to form the desired rope. The tension caused by the twisting kept the strands from unraveling. Below are examples of finished cordage with various circumferences.

Another essential businessman was the sailmaker, who measured the masts and yards of a ship, designed and drew her sail plan, and made her sails. He did so in a sailloft, which was usually on an upper floor of a warehouse because the laying out of the patterns required a large, uninterrupted floor space. Oftentimes the sailmaker employed other men to actually do the sewing, and he trained apprentices in the trade. One of the most successful sailmakers of the 19th century was James Forten of Philadelphia. This particular sailloft belonged to Charles Mallory, who came to Mystic in 1816.

Mystic Seaport allows visitors to walk the streets of a small seaport that catered to whaleships and fishing boats in the 19th century. A variety of shops were necessary both for those who lived in the town, as well as those who visited it. Examples of the proprietors would be a shipsmith, a man who sold nautical instruments and repaired clocks, a printer, a tavern keeper, a banker, the volunteers of the reading room of the Seamen's Friend Society, a minister, a school master, a druggist, and a doctor. The lower left photo is of the H. R. & W. Bringhurst Drugstore and Doctor's Office. Notice the masts of a ship that are visible above the rooftops in the scene to the right.

Salem, Massachusetts, on the other hand, catered to ships from foreign ports, particularly those engaged in trade with the East and West Indies. Such maritime commerce required all cargo entering the port be examined and assessed duties by the customs collector and his employees. This Custom House in Salem was built in 1819. Nathaniel Hawthorne worked here as a Customs Surveyor was . He issued ships's measurement certificates, supervised inspections, and oversaw the weighers, gaugers, and boatmen who unloaded the cargo. He wrote about his experience in an essay at the beginning of The Scarlet Letter.

The bookcase containing the Custom House's ledgers and its vault were housed in the Collector's Public House, the offices to the right of the Custom House entryway. Merchants and ship masters came to the large counter to file the required paperwork before a vessel could put to sea or unload her cargo. Clerks recorded the information and copied documents in longhand, so good penmanship was essential.

Customs officials used these scales to weigh and tax goods brought into Salem. They were kept in the Scale House behind the Custom House and carted to the wharf for use on the ships before the cargo was unloaded.

When ships unloaded their cargo, they tied up at one of the fifty or so wharves that dotted Salem's shore. The left shows a picture of Central Wharf. In the background is Derby Wharf, and between these two was Hatch's Wharf. Derby Wharf is the oldest of the three, having been built in 1762. Central dates from 1791 and Hatch's from 1819. Fourteen warehouses lined Derby Wharf, which belonged to Elias Hasket Derby, who could see his wharf from his house. Derby House (pictured right) is the oldest brick house in Salem and was built about the same time as the wharf.

Goods destined for other ports were brought to the Public Stores, a bonded warehouse. They remained here until either the duties on them were paid, or they were sold at auction or loaded onto another ship for transport to another port. Salem's Public Stores was built on the back of the Custom House, but there were no interior doors to connect the two buildings.

Lighthouses were built to aid ships at sea from straying into dangerous coastal waters. The one above is the Cape Cod or Highland Lighthouse in North Truro. Miles Standish and his men stayed here on their second night ashore while seeking a good site to settle. Henry David Thoreau stayed in the house that is now the museum.

The one below is a replica of the Brant Point Lighthouse on Nantucket. The original was built in 1746 and was the second colonial lighthouse. The Brant Point Lighthouse seen here, though, dates from 1900 and is the shortest one in New England. Its light was visible from ten miles away. Lighthouses were also important for identifying harbors.

|

|

|

|

Copyright ©2008 Cindy Vallar