Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Medicine at

Sea

by Cindy Vallar

The

Medicine Chest

In 1720, Bartholomew

Roberts and the pirates who sailed with him

found themselves in a heated battle with pirate

hunters. His only option was to “cut and run,” so

the pirates dumped their guns and cargo overboard.

They eventually escaped but not without severe

damage to Fortune and her crew. Half were

dead or wounded, and many more would die, for their

surgeon, Archibald

Murray, had left the ship and no one else knew

how to amputate limbs or prevent gangrene. Having no

other options, the wounded were given enough rum to

lessen their pain and left to die. In 1720, Bartholomew

Roberts and the pirates who sailed with him

found themselves in a heated battle with pirate

hunters. His only option was to “cut and run,” so

the pirates dumped their guns and cargo overboard.

They eventually escaped but not without severe

damage to Fortune and her crew. Half were

dead or wounded, and many more would die, for their

surgeon, Archibald

Murray, had left the ship and no one else knew

how to amputate limbs or prevent gangrene. Having no

other options, the wounded were given enough rum to

lessen their pain and left to die.

This is but one account of how sailors fared without

a doctor to tend them. If the ship possessed a medicine

chest, the captain designated someone to tend

patients. That person needed to be able to read and

write, but if he lacked knowledge of Latin, deciding

which medications to give became a problem since

bottles were labeled in that language rather than

the language of the tender. If the ship lacked a medicine

chest, a wounded or ill pirate found his fate

in God’s hands. When William

Phillips injured his leg, Captain John

Phillips allowed John Rose Archer to tend the man.

Archer had some skill with a saw, but cauterization

was beyond his understanding. The red-hot axe he

used to burn the stump destroyed too much and

William was left with even worse wounds than before.

Surgeons who plied their trade at sea, rather than

on land, were not new. They sailed with Roman

warships, and during medieval times, they

accompanied nobility and prelates on their voyages.

When the Spanish Armada sailed in 1588, the

eighty-five surgeons and their assistants were

unable to stop the dysentery

and typhus

that swept the ships.

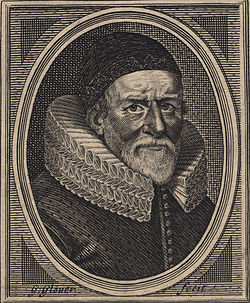

John

Woodall’s The

Surgeons Mate, first published in 1617,

aided many in treating what ailed a ship’s crew. The

manual listed the instruments and medicines found in

the medicine chest, and explained how to use them.

Special instructions explained what to do for

medical emergencies, such as an amputation. Various

ailments were also discussed, especially scurvy.

Woodall provided his readers with 281 remedies, but

of the herbs used, he warned that only fourteen were

“most fit to be carried": rosemary,

mint, melilot,

clover, horse radish, comfrey, sage, thyme,

absinthe,

blessed thistle, balm mint, juniper, hollyhock,

pyrethrum, and angelica.

Among the tools and supplies found in medicine

chests were knives, razors, “Head-Sawes,”

cauterizing irons, forceps, probes and spatulas for

drawing out splinters and shot, syringes, grippers

for extracting teeth, scissors, “Stitching quill and

needles,” splints, sponges, “clouts” (soft rags),

cupping glasses, blood porringers, chafing dishes,

mortar and pestle, weights and scales, tinderbox,

lantern, and plasters. This was why medicine chests

were prized almost as much as gold. In fact, when

Blackbeard blockaded

the port of Charleston, South Carolina, he

demanded such a chest in exchange for his hostages

(leading citizens of the town). Contemporary

accounts detailing the incident placed the value of

the medicine chest at between £300 to £400. John

Woodall’s The

Surgeons Mate, first published in 1617,

aided many in treating what ailed a ship’s crew. The

manual listed the instruments and medicines found in

the medicine chest, and explained how to use them.

Special instructions explained what to do for

medical emergencies, such as an amputation. Various

ailments were also discussed, especially scurvy.

Woodall provided his readers with 281 remedies, but

of the herbs used, he warned that only fourteen were

“most fit to be carried": rosemary,

mint, melilot,

clover, horse radish, comfrey, sage, thyme,

absinthe,

blessed thistle, balm mint, juniper, hollyhock,

pyrethrum, and angelica.

Among the tools and supplies found in medicine

chests were knives, razors, “Head-Sawes,”

cauterizing irons, forceps, probes and spatulas for

drawing out splinters and shot, syringes, grippers

for extracting teeth, scissors, “Stitching quill and

needles,” splints, sponges, “clouts” (soft rags),

cupping glasses, blood porringers, chafing dishes,

mortar and pestle, weights and scales, tinderbox,

lantern, and plasters. This was why medicine chests

were prized almost as much as gold. In fact, when

Blackbeard blockaded

the port of Charleston, South Carolina, he

demanded such a chest in exchange for his hostages

(leading citizens of the town). Contemporary

accounts detailing the incident placed the value of

the medicine chest at between £300 to £400.

Unlike today, medicines of the past had to be put

together similar to how a cook baked a cake. The

recipe for a medication consisted of a curative

agent, water or oil, flavoring, and the compound

used to comprise how the medication was given, for

example as a pill or an ointment. The base for the

latter might have been glycerin or lard. Wax

sometimes held a pill together. Ingredients in

ointments and liniments might include mercury,

turpentine, sassafras, thyme, hemlock,

eucalyptole, and/or sulfur. Medicines that were

ingested usually needed some flavoring to make them

palatable; vanilla, honey, licorice, sugar, nutmeg,

ginger, and mint were some that were used. Depending

on what ailed the patient, the pirate might endure bloodletting

to remove toxins from the blood, blisters (a caustic

agent applied with flannel or leather), salves,

clysters (medicines given rectally), or hot, moist

cloths used to relieve pain.

Perhaps Blackbeard required the medicines and

instruments to treat syphilis,

a common plague among sailors and pirates who

frequented brothels when on shore. Of course, his

crew might also have suffered from any number of

other problems, for danger lurked almost everywhere

aboard a wooden ship. Aside from the rats, weevils,

lice, and cockroaches, livestock was kept aboard and

sometimes had free reign of the deck, making for

unsanitary conditions. The pirates’ clothing was

often wet or damp. Depending on where they sailed,

nature might also inflict hardships: sunburn, heat

exhaustion, sunstroke, hypothermia, exposure, or

frostbite. Their work was equally hazardous and

sores, cuts, and bruises were the norm. Scurrying up

or down the rigging and the frequent movement of

both the ship and mast sometimes caused sailors to

lose their footing and fall. Landing in the water

often meant the man drowned, for knowing how to swim

wasn’t a requirement for being either a sailor or a

pirate. If he was lucky enough to be retrieved from

the water, sailors held the victim by his heels and

shook him to remove any water in his chest.

Working aloft to furl the

mainsail

(Source: Nautical Illustrations, Dover)

Landing on the deck might fracture

a person’s skull or kill him. In 1833, Billy Bridle1 was

aloft in the topmast crosstrees. When he tried to

slide down the topgallant halyards, he burned his

hands, lost his grip, fell to the deck (a distance

of twenty feet), and died instantly. Those who

didn’t die from a fall often exhibited symptoms of

“lethargie or frenzie, madnesse, losse of memory,

deadish sleep, giddinesse, apoplexie, paralysis, and

divers other like accidents.” (Friedenberg, 14) From

the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries,

surgeons treated such head wounds with desiccation

and cicatrization. When the skull bone collapsed, he

raised the depressed fragments and removed any

splinters. Wounds to the chest and abdomen, however,

were left in God’s hands.

Pirates, who visited lands not explored before, also

encountered additional dangers. Alexandre

Exquemelin wrote of the insects on Hispañola:

The gnats

of the third species exceed not the bigness of a

grain of mustard. The colour is red. These sting

not at all, but do bite so sharply upon the

flesh as to create little ulcers therein. When

it often comes that the face swells and is

rendered hideous to the view, through this

inconvenience. (Esquemeling, 33)

.jpg) The

plants could be equally dangerous. He encountered a

manchineel tree near the shore. Although similar to

apples back home, the fruit was poisonous. The

plants could be equally dangerous. He encountered a

manchineel tree near the shore. Although similar to

apples back home, the fruit was poisonous.

. . .

these apples being eaten by any person, he

instantly changes colour, and such an huge

thirst seizes him as all the water of the Thames

cannot extinguish, he dying raving mad within a

little while after. . . . This tree affords also

a liquor, both thick and white . . . which, if

touched by the hand, raises blisters upon the

skin, and these are so red in colour as if it

had been deeply scalded with hot water. One day

being hugely tormented with mosquitos . . . and

as yet unacquainted with the nature of this

tree, I cut a branch thereof, to serve me

instead of a fan, but all my face swelled the

next day and filled with blisters, as if it were

burnt to such a degree that I was blind for

three days. (Esquemeling, 32)

Depending on a pirate’s

ailment, the surgeon might prescribe one of nine

different types of medicines. Aquae – such as

cinnamon water, licorice juice, and fortified

peppermint water – cured hiccups and “stoppeth

vomiting, cureth choler, griping paine of the belly

. . .” according to John Woodall. (Druett, 7)

Spirits, salts, and tinctures – like salts of

wormwood, vinegar, and quicksilver

– cured a variety of ills from urinary problems to

fever. Balsams and resins were given orally or

applied to the skin. Sanguis Draconis, also

known as Dragon’s

Blood, was the resin made from the agave and

rattan palm. Garnet in color, the ground powder was

an astringent and “closeth up wounds.” (Druett, 8)

It was also used to make the varnish used on

violins. Around 1640, Jesuit priests introduced

Peruvian bark (quinine)

to Europe from South America. It was used to cure

intermittent fevers, such as malaria.

It should

be taken in the intermissions between the hot

stages, in the dose of a grain every hour, an

emetic at the commencement of the chill, and a

purge of Calomel and Jalap afterwards having

been given before commencing with the quinine.

(Druett, Rough Medicine, 61)

Syrups were made from

almonds, red roses, saffron, lemons, and other

plants. On board a ship, the surgeon might mix

vinegar of squills (hyacinth) with sugar and honey,

before giving it to a pirate to clear mucus from his

bronchial tubes. Oleum or oils, like oil of Saint

John’s Wort, were applied to the skin. Scottish

surgeons might have used this to treat wounds. The

Scots believed that Saint

Columba favored the plant because it was

associated with John the Evangelist and the Virgin

Mary, although the plant was used long before

Christianity came to Scotland in sacred ceremonies

and to prevent “fairies from spiriting people away

while they slept.” (Darwin, 96) Opiates and theriacs

were also used. An early patent medicine with opium

in it was “Methridatum,” which Woodall recommended

for those “fearfull of waters” and to cure “the

bites of serpents, mad dogs, wild beasts, and

creeping things” (Druett, 8), all of which a pirate

might encounter when visiting exotic places.

Unguents were used to treat burns and abrasions.

Plasters drew bad humors from the body or to treat

open infections, such as wounds received in battle.

In 1500, Giovanni de Vigo, a Roman doctor, treated

syphilis with a poultice called Emplastrum de

Ranis cum Mercurio. Its ingredients consisted

of frogs, “earthworms, viper’s flesh, human fat,

wine, grass from northern India, lavender from

France, chamomile from Italy, white lead, and

quicksilver.” (Druett, 9) One of the oddest plasters

was Pracelsi and was used to treat wounds

sustained in battle. The ingredients, brewed in

autumn, included “burnt earthworms, dried boar’s

brain, pulverized Egyptian mummy, crushed rubies,

bear’s fat, and moss from the skull of a hanged man

which had been collected from the gibbet at moonrise

with Venus ascending.” (Druett, 9) One might think

the plaster was then applied to the soldier’s wound;

in fact, it was applied to the sword that sliced

him.

The last type of medicine came from herbs and roots.

Chamomile flowers soothed headaches and helped with

kidney problems. Other examples included wormwood,

cinnamon, saffron,

rose petals, juniper berries, sarsaparilla root,

mustard seeds, and ginger.

Disease

The most common type of ailment that surgeons

treated was a disease of some kind. To men like John

Woodall, sin was the primary cause of disease,

although the noxious fumes emanating from bilge

water ran a close second. Aside from living a moral

life – not something usually associated with pirates

– the best way to stay healthy was to avoid stinking

vapors and cemeteries whenever possible, and protect

oneself from the night air. Diseases had a nasty

habit of invading ships where large numbers of

people were gathered together in confined places.

Surgeons recognized this fact early in the fifteenth

century. It was one reason that Sir Francis

Drake had to curtail some of his expeditions

against the Spaniards in the West Indies. He wrote

in his journal:

. . . we were not many dayes at

Sea but there began amongst our people such

mortality, as in a few dayes there were dead

above two or three hundred men. And until some,

seven or eight dayes after our coming from Saint

Jago, there had not dyed any one man of

sicknesse in all the Fleet: the sicknesse shewed

not his infection, wherewith so many were

stroken untill we were departed thence, and

there seazed our people with extreeme hot

burning and continuall ague, whereof some very

few escaped with life and yet those for the most

part not without great alteration and decay of

their wits and strength for a long time after.

In some that dyed were plainly shewn the small

spots, which are often found upon those that be

infective with Plague. (Friedenberg, 16) . . . we were not many dayes at

Sea but there began amongst our people such

mortality, as in a few dayes there were dead

above two or three hundred men. And until some,

seven or eight dayes after our coming from Saint

Jago, there had not dyed any one man of

sicknesse in all the Fleet: the sicknesse shewed

not his infection, wherewith so many were

stroken untill we were departed thence, and

there seazed our people with extreeme hot

burning and continuall ague, whereof some very

few escaped with life and yet those for the most

part not without great alteration and decay of

their wits and strength for a long time after.

In some that dyed were plainly shewn the small

spots, which are often found upon those that be

infective with Plague. (Friedenberg, 16)

The actual disease Drake

described might have been typhus,

cholera,

yellow

fever, or bubonic

plague. He believed the night air was the

culprit for the affliction. Even the surgeon died,

and Drake returned home without any plunder to make

up for the sacrifices he and his men endured.

Among the artifacts recovered from the wrecks of Samuel Bellamy’s Whydah

and Blackbeard’s

Queen Anne’s Revenge

were pewter syringes.

These were used to administer mercury to those who

suffered from syphilis. First described in Europe in

1494, the name stems from a poem Girolamo

Frascatoro wrote in 1530, about a shepherd

named Syphilisive

Morbus Gallicus. The term “syphilis” wasn’t

really applied to the disease until the 1800s.

Spanish sailors called it the French pox, while the

French called it the Spanish Disease.

What did a pirate endure if he contracted syphilis?

The disease had three stages.

- Chancres formed

where contact with an infected person occurred.

These often healed, leaving small scars.

- Six to eight weeks

later, the pirate seemed to contract the flu and

developed a skin rash. Doctors often

misdiagnosed this stage because of its

resemblance to small pox and measles. The

patient soon recovered and believed himself

cured. During this stage, syphilis was

contagious, and the pirate often infected many

others. After two years, the disease entered a

dormant stage.

- The final stage

occurred when syphilis attacked the body’s

systems many years later. Many went mad or blind

before they died.

An early treatment2 for

syphilis came from the native peoples in the West

Indies. They used a resin found in evergreen holy

wood or guaiacum.

The more effective treatment was to administer mercury

orally, through a vapor bath, or in the case of

pirates, by injecting the medication into the penis with a

syringe. A salve was applied to the chancres that

developed when first contracted. An early treatment2 for

syphilis came from the native peoples in the West

Indies. They used a resin found in evergreen holy

wood or guaiacum.

The more effective treatment was to administer mercury

orally, through a vapor bath, or in the case of

pirates, by injecting the medication into the penis with a

syringe. A salve was applied to the chancres that

developed when first contracted.

Since syphilis was more or less an occupational

hazard, surgeons treated most pirates over a

long period of time. Whether the mercury was

ingested orally or absorbed through unguents, it

often produced a metallic taste in their mouths that

caused patients to salivate. They didn’t complain

overmuch since many thought it was just the price

they paid for contracting the disease in the first

place. Mercury poisoning sometimes occurred. When

this happened, the pirate lost weight, drooled, had

foul breath and blurred vision, and slurred his

speech. He also had trouble maintaining his balance.

If the treatment for syphilis wasn’t stopped, his

kidneys eventually ceased functioning and he died.

Another disease

that plagued anyone who remained at sea for long

periods of time was scurvy,

which killed more mariners than all the other

diseases, natural disasters, and fights combined.

(Historians conservatively place the number of

deaths at more than 2,000,000 between Columbus’s

first voyage to the New World and the mid-nineteenth

century.) Even physicians of Ancient

Greece didn’t know what caused it. A variety

of folk cures were developed, some of which were

more deadly than the disease. Among these were

swallowing sea water to purge the illness, bleeding,

digesting sulfuric acid, anointing open sores with

mercury paste, and increasing the sailor’s workload.

(The thinking on the last cure was because scurvy

made the sailor lethargic.)

Scurvy

usually struck about four weeks after a ship left

port. In 1596, William Clowes, an English surgeon at

sea, described what his men suffered: Scurvy

usually struck about four weeks after a ship left

port. In 1596, William Clowes, an English surgeon at

sea, described what his men suffered:

Their gums

were rotten even to the very roots of their

teeth, and their cheeks hard and swollen, the

teeth were loose neere ready to fallout…their

breath a filthy savour. The legs were feeble and

so weak, that they were not scarce able to

carrie their bodies. Moreover they were full of

aches and paines, with many bluish and reddish

staines or spots, some broad and some small like

flea-biting. (Brown, 34)

Just like the pirates and

sailors, those who treated them sometimes endured

the same disease. Another surgeon who sailed on an

English ship in the sixteenth century wrote:

It rotted

all my gums, which gave out a black and putrid

blood. My thighs and lower legs were black and

gangrenous, and I was forced to use my knife

each day to cut into the flesh in order to

release this black and foul blood. I also used

my knife on my gums, which were livid and

growing over my teeth. . . . When I had cut away

this dead flesh and caused much black blood to

flow, I rinsed my mouth and teeth with my urine,

rubbing them very hard. . . . And the

unfortunate thing was that I could not eat,

desiring more to swallow than to chew. . . .

Many of our people died of it every day, and we

saw bodies thrown into the sea constantly, three

or four at a time. For the most part they died

without aid given them, expiring behind some

case or chest, their eyes and the soles of their

feet gnawed away by the rats. (Brown, 34)

Sir Francis Drake recorded

several outbreaks of scurvy. In 1740, Commodore

George Anson set sail with 2,000 men on a trip

to circumnavigate the world. Of those original

sailors, only about 200 returned to England in 1744.

Ninety percent of those who died succumbed from

scurvy. Sir Francis Drake recorded

several outbreaks of scurvy. In 1740, Commodore

George Anson set sail with 2,000 men on a trip

to circumnavigate the world. Of those original

sailors, only about 200 returned to England in 1744.

Ninety percent of those who died succumbed from

scurvy.

Sir Richard

Hawkins, another Elizabethan

Sea Dog, referred to it as “the plague of the

sea, and the spoil of mariners.” (Druett, Rough

Medicine, 142) In 1593, he was the first to

suggest a remedy: “most fruitfull for this

sicknesse, is sower oranges and lemons.” (Druett, Rough

Medicine, 143) Johan Friedrich Bachstrom

believed scurvy developed because of the lack of

fresh fruits and vegetables. When he announced this

in the 1730s, his fellow practitioners ignored him

because no one else believed this to be true. In

1753, James Lind

published Treatise

of Scurvy, but like Bachstrom his advice

was largely ignored. Another forty-two years passed

before Sir Gilbert

Blane convinced the British Admiralty to

provide sailors with a daily ration of lemon juice.

In doing so, the navy virtually eliminated scurvy

from their ships.

Amputation

While pirates preferred not to engage

in a sea battle, fighting did occur. Sometimes it

was confined to the actual boarding of the prize;

sometimes the hunter and prey exchanged volleys from

their guns. The injuries inflicted were bloody and

sometimes lethal. After the American frigate United

States defeated HMS Macedonian

on 25 October 1812, a British seaman wrote: While pirates preferred not to engage

in a sea battle, fighting did occur. Sometimes it

was confined to the actual boarding of the prize;

sometimes the hunter and prey exchanged volleys from

their guns. The injuries inflicted were bloody and

sometimes lethal. After the American frigate United

States defeated HMS Macedonian

on 25 October 1812, a British seaman wrote:

The first

object I met was a man bearing a limb, which had

just been detached from some suffering wretch. .

. . The surgeon and his mate were smeared with

blood from head to foote: they looked more like

butchers than doctors. . . .

Our

carpenter . . . had his leg cut off. I helped to

carry him to the after wardroom, but he soon

breathed out his last life there, and then I

assisted in throwing his mangled remains

overboard. . . . It was with exceeding

difficulty I moved . . . it was so covered with

mangled men and so slippery with blood. (Estes,

65)

James Lowry served as a

Royal Navy ship’s surgeon in the Mediterranean fleet

when it attacked Fort Saint Elmo on Malta in

December 1798. His words clearly gave witness to the

dangers during a sea battle, and to the fact that

during a fight, there was no time to mourn the dead.

As I was

dressing a wounded man, a cannon ball struck a

young gentleman on the head dashing his brains

upon all sides; part of them blinded me. At this

moment a splinter struck my head and rendered me

insensible for quarter of an hour. Upon my

recovery, I could hardly persuade myself but

what I was mortally wounded, from being

completely besmeared with blood and brains.

Alas! when I beheld my friend and companion

without a head, I could not avoid reflecting

with emotions of grief; but the field of battle

being no place for weeping or lamentations . . .

I contented myself with the usual expression

upon the field of battle – poor fellow, there he

lies and ends his career. (Lowry, 44)

When a pirate lay hurt,

he usually suffered from a puncture, a slash, or an

amputation. Bullets, shrapnel, and splinters often

caused the first type of wound, whereas a cutlass or

knife caused the second. Projectiles

(ball, shot, or chain) inflicted the last type of

injury. These could inflict a variety of wounds,

especially if the projectile struck wood. Splinters

flew or a mast toppled, crushing anyone unlucky

enough to be under it when it fell. Gunners suffered

scorched burns from spilled gunpowder ignited by a

spark. Descriptions of Dominique

You, one of Jean

Laffite’s privateers, mentioned powder burns

over his left eye that gave him a menacing or grim

appearance. If an explosion caused a fire, sailors

often suffered severe burns.

A wounded pirate eventually found himself placed

upon planks laid across casks to form a makeshift operating

table, if a real table wasn’t available. An

old sail or other cloth might be draped over the

planks. Nearby, smaller flat surfaces or sea chests

held the surgeon’s

instruments and on the floor was a bucket

where amputated body parts were dropped until they

could be carried above deck and tossed into the sea.

Drake, like the buccaneers who came later, often

raided land targets. During one such raid, the party

was ambushed and he was wounded.

The

generall himself was shot in the face under his

right eye and close by his nose, the arrow

piercing a marvelous way in under basis cerebris

with no small danger of his life besides that,

he was grievously wounded in the head. The rest

being nine persons in the boat, were deadly

wounded in divers parts of their bodies, if God

almost miraculously had not give cure to the

same. For our chief Surgeon being dead and the

others absent by the loss of our vice-admirall,

and having none left us but a boy, whose good

will was more than any skil he had, we were

little better than altogether destitute of such

cunning and helps as so grievous a state of so

many wounded bodies did require. Notwith

standing God, by the very good advice of our

Generall and the diligent putting too of every

man’s help, did give such speedy and wonderful

cures, that we had all great comfort thereby and

yielded God the glory, whereof.

(Friedenberg, 17)

Doctors didn’t know what

caused infection back then, so instruments weren’t

sterilized and bandages weren’t necessarily clean.

Neither did the surgeon wash his hands between

patients. To tend a puncture or slash wound, he

removed “unnatural things forced into the wound” (a

musket ball, pieces of wood or cloth), using a

forceps. (Friedenberg, 11) Then he washed the wound

with water or alcohol, packed it with lint scraped

from linen sheets, and wrapped a bandage around it.

If sutures were needed, he used waxed thread that

might dangle from his lips until needed. Should

infection set in, the preferred treatment was to

bleed the patient.

A pirate who suffered a severe wound to his arm or

leg was more likely to have it amputated since the

tissue and muscle were severely damaged. The last

thing anyone wanted was to have the wound turn

gangrenous, for that usually resulted in death. Most

doctors believed the patient was more likely to

survive if a clean cut was made than if the surgeon

allowed the limb to heal without surgery. John Hoxse,

a carpenter aboard USS Constellation

in 1800, wrote:

as I was

standing near the pump, with a top maul in my

right hand, with the arm extended, a shot from

the enemy’s ship entered the port near by, and

took the arm off just above the elbow, leaving

it hanging by my side by a small piece of skin;

also wounding me severely in the side, leaving

my entrails all bare. I then took my arm in my

left hand, and went below . . . and requested

the surgeon to stop [the bleeding in] my arm [as

it] was already off. He accordingly stopped the

effusion of blood, and I was laid aside among

the dead and wounded, until my turn came to have

my wounds dressed. . . . I was so exhausted that

I fell asleep . . . until . . . I was . . . laid

on a table, my wounds washed clean, and my arm

amputated and thrown overboard. (Langley,

58)

Hoxse received these

wounds during the Quasi-War with France, but didn’t

record the event until forty years later.

When amputation

was required, it had to be done within twenty-four

hours of the wounding. A seaman aboard HMS Macedonian

assisted during an operation.

We held

[one man] while the surgeon cut off his leg

above the knee. The task was most painful to

behold, the surgeon using his knife and saw on

human flesh and bones as freely as the butcher

at the shambles. (Estes, 65)

An injured pirate’s

clothing was cut off and a tourniquet was applied to

slow the bleeding. The surgeon gave him a stick to

bite down on, and while the ship pitched and rolled,

the operation began. First, the surgeon used a

scalpel to cut open the skin above the wound. He

sliced through the muscle to the bone with a knife.

The mate who assisted pulled back the flesh to

expose the bone and a leather strap encircled the

bone to keep it clear of obstruction. Using a saw,

the surgeon then cut the bone and tossed the removed

limb into the bucket.

A strip of

cotton cloth about 2 feet long and 8inches wide

torn up the centre from one end for half the

length is then to be drawn over the flesh closed

around the bone. The ends are brought together

and the whole serves to draw the skin and flesh

up while the bone is sawed off. Very little pain

is felt from sawing a bone – If there is any

splinter or corner left it should be pinched off

with nippers.3

(Druett, Rough

Medicine, 121)

Hot tar was painted on

the bloody stump or the wound was cauterized with a

hot iron.4 This

stopped the profuse bleeding that occurred. Once the

surgeon removed the tourniquet, he placed two large

“rounds” of linen over the stump and lashed it in

place with strips of linen. If a wool stocking cap

was available, this was also pulled over the stump.

The entire operation took eight to ten minutes. The

pirate’s chances of survival? Fifty-fifty.

Contrary to what most people believe, the injured

underwent surgery wide awake. They weren’t given rum

or other alcoholic drinks to numb them for two

reasons. Anesthetics had yet to be invented and the

doctors didn’t want their patients dying from weak

hearts. Opiates or grog weren’t given to them until

after the operation to relieve pain.

Sometimes there was nothing a surgeon could do to

help a wounded man. When this happened, he often

died a slow and painful death. Robert Young, the

surgeon aboard Ardent at the Battle of

Camperdown in 1797, wrote:

Joseph

Bonheur had his right thigh taken off by a

cannon shot close to the pelvis, so that it was

impossible to apply a tourniquet; his right arm

was also shot to pieces. The stump of the thigh,

which was very fleshy, presented a dreadful and

large surface of mangled flesh. In this state he

lived near two hours, perfectly sensible and

incessantly called out in a strong voice to me

to assist him. . . . All the service I could

render . . . was to put dressing over the part

and give him drink.

While pirate

surgeons lacked a full understanding of what

caused disease, they labored as best they could to

cure ship fever (typhus), gripes and fluxes

(dysentery), smallpox, measles, pleurisy and

catarrhal fever, scurvy and beriberi, food

poisoning, venereal disease, yellow fever, and

malaria. The same was true for serious wounds and

injuries. Some surgeons, like Alexandre Exquemelin

and Lionel Wafer, studied and used the cures

recommended by the people native to the various

lands the buccaneers visited. Pirates understood the

value of having a surgeon amongst them. That’s why

doctors and medicine chests were prized plunder.

Notes:

1. Billy Bridle was actually

Rebecca Young, and it was only upon Billy's death

that those on the ship learned he was actually a

woman. She had sailed as a man for two years.

2. Not until the 1940s was

penicillin used to treat syphilis.

3. Dr. John B. King’s

instructions on amputating a leg.

4. The tenaculum, which was used

to tie off arteries, wasn’t employed until after

1750.

For additional information on medicine at sea in the

Age of Sail I recommend:

Pyrate Surgeons

Bibliography

Anderson, Ron. “The

Most Dangerous Man Aboard,” No Quarter Given

(July 1999), 10-11.

Breverton, Terry. Black

Bart Roberts: The Greatest Pirate of Them All.

Pelican, 2004.

Brown, Stephen R. Scurvy:

How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved

the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail.

St. Martin’s Press, 2003.

Coote, Stephen. Drake:

The Life and Legend of an Elizabethan Hero.

St. Martin’s Press, 2003.

Cordingly, David. Women

Sailors & Sailors’ Women. Random House,

2001.

Daniel, Mike. “The

French Pox,” No Quarter Given (September

1999), 10.

Darwin, Tess. The

Scots Herbal: The Plant Lore of Scotland.

Mercat Press, 1997.

Druett, Joan.

“Privateer Medicine Chest,” No Quarter Given

(September 1999), 7-9.

Druett, Joan. Rough

Medicine. Routledge, 2000.

Eastman, Tamara. “The

Medicine Chest,” No Quarter Given (July

1999), 5.

Estes, J. Worth. Naval

Surgeon: Life and Death at Sea in the Age of

Sail. Science History Publications, 1998.

Folsom, James. Mariner’s

Medical Guide. James Folsom & Co.,

1864.

Friedenberg, Zachary B.

Medicine Under Sail. Naval Institute Press,

2002.

Lampe, Christine

Markel. “Three Special Syringes,” No Quarter

Given (July 1999), 5.

Langley, Harold D. A

History of Medicine in the Early U.S. Navy.

Johns Hopkins University, 1995.

Lee, Robert E. Blackbeard

the Pirate: A Reappraisal of His Life and Times.

John F. Blair, 2002.

Little, Benerson. The

Sea Rover’s Practice. Potomac Books, 2005.

Longfield-Jones, G. M.

“Buccaneering Doctors,” Medical History 36

(1992), 187-206.

Lowry, James. Fiddlers

and Whores: The Candid Memoirs of a Surgeon in

Nelson’s Fleet. Chatham, 2006.

Rediker, Marcus. Between

the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. Cambridge

University, 1999.

Ringrose, Basil. “The

Dangerous Voyage and Bold Attempts of Captain

Bartholomew Sharp and Others Performed Upon the

Coasts of the South Sea for the Space of Two

Years,” in John Esquemeling’s The Buccaneers

of America. The Rio Grande Press, 1992.

Selinger, Gail. Complete

Idiot’s Guide to Pirates. Alpha, 2006.

Stewart, Wesley.

“Sea-going Surgeons,” No Quarter Given

(July 1999), 4.

Vallar, Cindy. "Pyrate

Surgeons," Pirates and Privateers

(May-July 2007).

Review

Copyright ©2007 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |