Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Pirate

Tactics

by Cindy Vallar

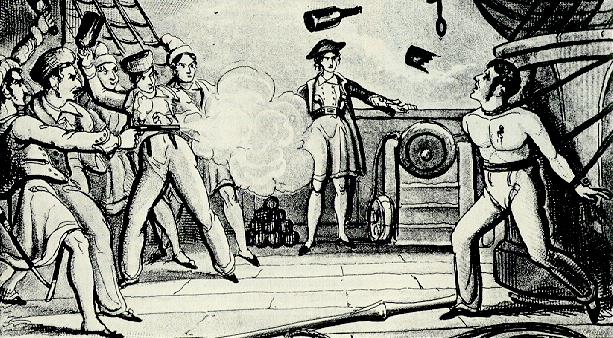

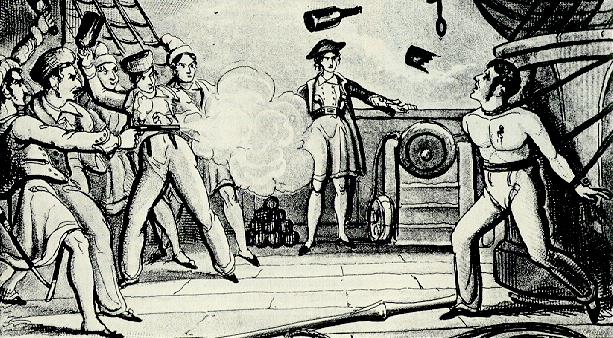

Boarding by unknown artist

(Source: Dover's Pirates)

Contrary

to popular opinion, pirates rarely just spied a ship

and attacked it. They gathered intelligence about

their target and the people who guarded it and

considered “what if” scenarios. Planning only worked

if the details were kept secret, so only those with

a need to know participated in this stage of the

project.

Before any attack could

be planned, pirates needed to acquire information

about possible targets. The more knowledge gathered,

the better their chance of success. Where did they

acquire information about potential targets? Taverns

and coffeehouses

were ideal places to learn about incoming and

outgoing ships. Who commanded a vessel? How many men

were aboard? What cargo did she carry? Before any attack could

be planned, pirates needed to acquire information

about possible targets. The more knowledge gathered,

the better their chance of success. Where did they

acquire information about potential targets? Taverns

and coffeehouses

were ideal places to learn about incoming and

outgoing ships. Who commanded a vessel? How many men

were aboard? What cargo did she carry?

In A New

Voyage Round the World, published in

1697, William

Dampier described what type of information his

fellow buccaneers sought when planning a raid on a Spanish

town.

For the

privateers . . . make it their business to

examine all prisoners that fall into their

hands, concerning the country, town, or city

that they belong to; whether born there, or how

long they have known it? How many families,

whether most Spaniards? Or whether the major

part are not copper-colour’d, as Mulattoes,

Mustesoes, or Indians? Whether rich, and what

their riches do consist in? And what their

chiefest manufactures? If fortified, how many

great guns, and what number of small arms?

Whether it is possible to come undescrib’d on

them? How many look-outs or centinels; for such

the Spaniards always keep? And how the look-outs

are placed? Whether possible to avoid the best

landing; with innumerable other such questions,

which their curiosities led them to demand. And

if they have had any former discourse of such

places from other prisoners, they compare one

with the other; then examine again, and enquire

if he or any of them are capable to be guides to

conduct a party of men thither: if not, where

and how any prisoner may be taken that may do

it; and from thence they afterwards lay their

schemes to prosecute whatever design they take

in hand. (Little, 80)

Pirates

always interrogated sailors and passengers on seized

vessels. The threat of torture was often enough to

make them talk, but when necessary, pirates tortured

their prisoners. This information needed to be

confirmed whenever possible, for victims would lie

in hopes of saving their lives. Torture also

revealed hidden booty aboard the prize. On 14

September 1723, Princess had almost reached

Barbados when George

Lowther attacked. Successful in the capture,

he and his men put lit fuses between the fingers of

the surgeon and second mate until the two men

revealed the hiding place of fifty-four ounces of

gold. Pirates

always interrogated sailors and passengers on seized

vessels. The threat of torture was often enough to

make them talk, but when necessary, pirates tortured

their prisoners. This information needed to be

confirmed whenever possible, for victims would lie

in hopes of saving their lives. Torture also

revealed hidden booty aboard the prize. On 14

September 1723, Princess had almost reached

Barbados when George

Lowther attacked. Successful in the capture,

he and his men put lit fuses between the fingers of

the surgeon and second mate until the two men

revealed the hiding place of fifty-four ounces of

gold.

Yet prisoners and places frequented by sailors

weren’t the only sources of information pirates used

in gathering intelligence. Merchants, smugglers,

native peoples, cimarrones

(escaped slaves), and others who lived on the

fringes of society or were friendly to pirates also

supplied vital information. Whenever possible,

pirates compared new revelations with what they

already knew or had heard to verify the truth of the

intelligence.

How did pirates locate potential targets? Sometimes,

they sailed near established trade routes and

attacked whatever ships crossed their path. Other

times, they hid in coves or straits where they

waited to ambush unsuspecting prey. In these cases,

pirates relied on their acquired knowledge of where

ships passed at given seasons of the year rather

than gathering more detailed information on possible

targets. Pirates preferred hunting in coastal waters

instead of the open sea because “[a] ship crossing

from England to the New York colony might sight many

sail during the voyage, or none at all.” (Little,

77) At some point, all vessels navigated coastal

waters, so while the risk increased when pirates

cruised close to shore, this area also provided the

greatest potential for locating prizes.

Pirates toss bottles at a

prisoner bound to the capstan

(Source: Pirate

Images)

The more familiar with the region pirates were, the

better their chances of finding prey. Accurate nautical

charts and knowledge of hazardous waters were

essential for any captain and/or navigator. If the

wait took too long, they might need to replenish

food and water, so knowledge of where to find these

supplies was important. Pirates also seized

waggoners, charts, logs, and other ship’s papers,

which might reveal the departure or arrival of

treasure ships or vessels carrying prized cargo.

Although sometimes incorrect, charts and atlases

provided pertinent details for navigating coastal

waters and locations where the vessels could hide,

careen, or resupply.

Other times, pirates targeted a specific ship,

although this was often the more dangerous way to

gain riches. They had to acquire information about

the ship, her cargo, and her approximate arrival or

departure time. No amount of intelligence gathering

guaranteed success, for unlike today, ships didn’t

arrive or depart on schedule. In this scenario,

pirates also had to consider “[v]ariables such as

wind, weather, quantities of provisions, wood, or

water, and simple timing” because each could impact

the mission’s success or failure. (Little, 76) If an

attack succeeded, one prize could make a pirate rich

beyond his dreams.

In

1579, Francis

Drake learned from a captured Spanish officer

that three treasure ships were expected – one bound

for Panama and two for Callao. Drake ordered a

captured Portuguese pilot to sail Golden

Hinde to Callao. Upon entering Lima’s

port city, almost half of Drake’s seventy crew

members boarded smaller vessels to sail close to the

anchored Spanish ships and cut their cables. Drake

hoped to seize the ships after the wind carried them

out to sea, but the wind died and the enemy ships

failed to move anywhere. As a result, he sailed

toward Panama to intercept the great galleon laden

with silver. In

1579, Francis

Drake learned from a captured Spanish officer

that three treasure ships were expected – one bound

for Panama and two for Callao. Drake ordered a

captured Portuguese pilot to sail Golden

Hinde to Callao. Upon entering Lima’s

port city, almost half of Drake’s seventy crew

members boarded smaller vessels to sail close to the

anchored Spanish ships and cut their cables. Drake

hoped to seize the ships after the wind carried them

out to sea, but the wind died and the enemy ships

failed to move anywhere. As a result, he sailed

toward Panama to intercept the great galleon laden

with silver.

Nuestra

Señora de la Concepción was sighted on 1

March. Rather than follow it, Drake

pretended to do the opposite. He also hung cables

and mattresses over the side of Golden Hinde

to slow the vessel. When the two ships came within

shouting distance, one of Drake’s prisoners warned

the captain of Concepción, so Drake ordered

marksmen to fire a volley and for bow chasers to

fire chain shot, which brought down the mizzenmast.

After Drake’s gunners fired shot from a larger gun,

the Spaniards surrendered while English archers

boarded the galleon. Concepción carried “a

great quantity of plate, 80 lb of gold, and 26 tons

of uncoined silver[,]” according to a contemporary

report, and it took five trips and six days to

transfer the booty to the Golden Hinde.

(Cordingly, 30) Today, the treasure would be worth

around UK £14 million (US $26 million), and was

sufficient not only to make rich men of all aboard

but also allowed Queen Elizabeth to pay

off her foreign debt.

Pirates

didn’t always attack ships, especially the buccaneers

of the seventeenth century. When they raided land

targets, they had to determine which weapons and

supplies were essential to achieve their goal.

Sometimes, the best way to secure information for

this type of operation was to spy out the terrain. A

year before Drake raided Nombre de

Dios, a port city on the Isthmus of Panama in

1572, he donned the disguise of a Spanish merchant

and visited the town where “. . . he inspected the

harbor and noted the location of the King’s

treasure-house. He had found a sheltered cove nearby

which would provide a safe anchorage. . . . He also

made contact with some of the escaped black slaves

called Cimaroons who lived in the surrounding jungle

and were always ready to revenge themselves on the

hated Spanish.” (Cordingly, 26-27) Pirates

didn’t always attack ships, especially the buccaneers

of the seventeenth century. When they raided land

targets, they had to determine which weapons and

supplies were essential to achieve their goal.

Sometimes, the best way to secure information for

this type of operation was to spy out the terrain. A

year before Drake raided Nombre de

Dios, a port city on the Isthmus of Panama in

1572, he donned the disguise of a Spanish merchant

and visited the town where “. . . he inspected the

harbor and noted the location of the King’s

treasure-house. He had found a sheltered cove nearby

which would provide a safe anchorage. . . . He also

made contact with some of the escaped black slaves

called Cimaroons who lived in the surrounding jungle

and were always ready to revenge themselves on the

hated Spanish.” (Cordingly, 26-27)

Once the intelligence was gathered and a plan

formulated, pirates set out on their venture. Their

leader, the captain, was someone willing to step

into the fray rather than wait on the sidelines

while his men did battle. His courage and daring

were essential, but so were his ability to be

flexible and his willingness to adapt his plans to

fit the altered situation. Pirates might plan for

every possible contingency, but fate often delivered

something unexpected.

When Drake and his band of seventy-three men

attacked Nombre de Dios, their first goal was to put

the shore battery of six guns out of commission.

Having achieved this, they divided; Drake attacked

from the east while his brother created a diversion

to the west. “Drake . . . marched into the town with

beating drums and the sounding of trumpets. There

was panic from the inhabitants, who imagined they

were being attacked by a huge force.” (Cordingly,

27) Then the unexpected occurred. Spanish soldiers

wounded Drake in the thigh, and a thunderstorm

soaked the pirates’ powder and matches, making their

weapons useless. The men wanted to give up, but

Drake convinced them otherwise. Ignoring the pain,

he led them to the treasure house, but once inside,

they found it empty. The treasure fleet had sailed

six weeks earlier; another shipment wouldn’t arrive

for months.

Whether the attack occurred on land or at sea,

surprise was essential. On land, fewer citizens had

a chance to hide their valuables or escape with

them. At sea, fewer pirates died and the prize

sustained less damage. Speed and mobility were also

important to the success of attacks. This was why

pirates favored fast ships that were easy to

maneuver and had shallow drafts.

Once the lookout

sighted a potential target, the pirates did not

immediately attack. They stalked the prey to

identify the type of ship, whether she rode low or

high in the water (full cargo vs. empty hold), and

to determine the prey’s possible firepower. This

intelligence gathering took several hours to several

days. “To discern the details of armament and crew

of an unknown vessel by naked sight alone – whether,

for example, the crew were many or few, and how many

ports or cannon the vessel might have – it had to be

no more than a few hundred yards away, and even then

many details were obscure. And because most

nations had other nations’ vessels in their naval

and merchant fleets . . . it was not possible to

determine nationality solely from design or general

characteristics.” (Little, 109) Once the lookout

sighted a potential target, the pirates did not

immediately attack. They stalked the prey to

identify the type of ship, whether she rode low or

high in the water (full cargo vs. empty hold), and

to determine the prey’s possible firepower. This

intelligence gathering took several hours to several

days. “To discern the details of armament and crew

of an unknown vessel by naked sight alone – whether,

for example, the crew were many or few, and how many

ports or cannon the vessel might have – it had to be

no more than a few hundred yards away, and even then

many details were obscure. And because most

nations had other nations’ vessels in their naval

and merchant fleets . . . it was not possible to

determine nationality solely from design or general

characteristics.” (Little, 109)

During the chase, the pirate captain watched how the

prey sailed. What sails did she carry? Where was she

headed? Did her captain alter course once he sighted

the unidentified ship (i.e. the pirate ship)? The

longer the prey remained on its present heading, the

better.

Sometimes, pirates used the ruse de guerre

to trick victims into allowing the pirate ship to

come so close to the prey that she could not

successfully defend herself once the pirates

revealed their true colors. They hoisted the same

nation’s flag, or that of an ally, as the prey. Le Sieur du

Chastelet des Boys, a traveler aboard a Dutch

ship in the 1600s, found himself in the midst of an

attack by Barbary

corsairs. When he sighted six Dutch ships

coming to the rescue, his relief was immeasurable

until “the Dutch flags disappeared and the masts and

poop were simultaneously shaded by flags of taffeta

of all colors, enriched and embroidered with stars,

crescents, suns, crossed swords and other devices.”

(Pirates, 87)

The ruse de guerre wasn’t always successful.

“False colors were so prevalent and so often misused

that identification according to colors was dubious

at best.” (Little, 117) For example, Captain John

Cornelius tried to convince an English slaver that

his ship, Morning Star, was a pirate hunter.

“About Ten Cornelius came up with them, and being

haled, answered, he was a Man of War, in Search of

Pyrates, and bid them send their Boat on board; but

they refusing to trust him, tho’ he had English

Colours and Pendant aboard, the Pyrate fired a

Broadside, and they began a running Fight of about

10 Hours, in which Time the negroes discharged their

Arms so smartly, that Cornelius never durst attempt

to board.” (Defoe, 600)

If pirates utilized the ruse de guerre in

combination with other deceptions, their chance of

success improved. To lure the intended target within

range, they might alter their sails or camouflage

the gunports. While most pirates hid belowdecks or

out of sight behind the gunwale, a few pirates

donned female attire and strolled the deck. When

pirates sailed with two ships, they sometimes

disguised one to appear as if it was a legitimate

ship that had taken the second vessel as a prize.

“[T]o attack two Spanish vessels, filibusters and

buccaneers flew a Spanish flag from a recently

captured Spanish ship, and from their boats as well.

But they also flew English and French colors from

the boats, giving a distinct impression that the

Spanish ship had captured the French and English.

The ruse succeeded. Of the two vessels that

approached, one was sunk with grenades, and the

other was captured.” (Little, 118)

Once pirates revealed their true intentions, they

often fired a shot across their prey’s bow as a

warning to strike her colors and surrender. If the

prey refused, the pirates attacked. To capture the

vessel and her cargo while inflicting the least

amount of damage as possible, their gunners peppered

the sails rather than raking the prey with

broadsides. Aloft, marksmen used muskets to clear

the deck. Officers and helmsmen were favorite

targets. “It helped even the odds against a stout

enemy, and overwhelmed a weaker one. . . . Twenty

men with muskets might do more damage to the prey’s

crew than a single six-pound round shot . . .”

(Little, p. 57) Grenadoes

also cleared the deck and wreaked havoc.

The smoke from these, as well as the guns, acted as

camouflage to disguise the boarding. Fifteen grenadoes

were found in the excavation of Samuel

Bellamy’s Whydah.

Before Blackbeard

and his crew boarded Lieutenant Maynard’s sloop,

they “threw in several new fashion’d Sort of

Grenadoes, viz. Case Bottles fill’d with Powder, and

small Shot, Slugs, and Pieces of Lead or Iron, with

a quick Match in the Mouth of it, which being

lighted without Side, presently runs into the Bottle

to the Powder, and as it is instantly thrown on

board, generally does great Execution, besides

putting all the Crew into a Confusion; but by good

Providence, they had not that Effect here; the Men

being in the Hold. Black-beard seeing few or

no Hands aboard, told his Men, that they were all

knock’d on the Head, except three or four; and

therefore, says he, let’s jump on board, and cut

them to Pieces. Whereupon, under the Smoak of

one of the Bottles just mentioned, Black-beard

enters with fourteen Men, over the Bows of Maynard’s

Sloop . . .” (Defoe, 81)

Cutlass,

flintlock, and axe

Cutlass,

flintlock, and axe

(Source: Author)

Blackbeard’s last stand against the Royal Navy was

equally brutal. “Black-beard and the

Lieutenant fired the first Shots at each other, by

which the Pyrate received a Wound, and then engaged

with Swords, till the Lieutenant’s unluckily broke,

and [Maynard] stepping back to cock a Pistol, Black-beard,

with his Cutlash, was striking at that Instant, that

one of Maynard’s Men gave him a terrible Wound in

the Neck and Throat, by which the Lieutenant came

off with only a small Cut over his Fingers. They

were now closely and warmly engaged, the Lieutenant

and twelve Men against Black-beard and fourteen,

till the Sea was tinctur’d with Blood round the

Vessel; Black-beard received a Shot into his

Body from the Pistol that Lieutenant Maynard discharg’d,

yet he stood his Ground, and fought with great Fury,

till he received five and twenty Wounds, and five of

them by Shot. At length, as he was cocking another

Pistol, having fired several before, he fell down

dead; by which Time eight more out of the fourteen

dropp’d, and all the rest, much wounded, jumped

over-board, and call’d out for Quarters, which was

granted, tho’ it was only prolonging their Lives a

few days.” (Defoe, 81-82)

Capture

of the Pirate, Blackbeard, 1718 by Jean Leon

Gerome Ferris (1920)

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

These tactics weren’t used only in Caribbean waters.

The Barbary corsairs employed them in the

Mediterranean. They “would fly a foreign flag in

order to ‘lure the unsuspecting victim within

striking distance.’ Then gunners perched on the

rigging would 'ply the shot with unabated rapidity,’

raking the victim’s deck. Meanwhile ‘the fighting

men stand ready, their arms bared, muskets primed,

and scimitars flashing, waiting for the order to

board.’” On the reis’s (captain’s) cue, the corsairs

swarmed the prize. “‘[T]heir war-cry was appalling;

and the fury of the onslaught was such as to strike

panic into the stoutest heart.’ After overcoming the

crew, the pirates chained survivors, who would

become hostages for ransom or slaves for sale,

manned the captured ship, and proceeded to their

home port.” (Lambert, 39)

Planning, intelligence gathering, daring,

quick-thinking, speed, mobility, and the ability to

adapt played roles in whether an endeavor succeeded

or failed. Perhaps this was why Bartholomew

Roberts became one of the most successful

pirates to sail the seas. Once, he and his men

stumbled upon a fleet of forty-two Portuguese ships,

bound for Lisbon, off the Bay of los todos

Santos. Although outnumbered and outmanned,

Roberts sailed Rover into the Portuguese

convoy and “. . . mix’d with the Fleet, and kept his

Men hid till proper Resolutions could be form’d,

that done, they came close up to one of the deepest,

and order’d her to send the Master on board quietly,

threat’ning to give them no Quarters, if any

Resistance, or Signal of Distress was made. The Portuguese

being surprised at these Threats, and the sudden

Flourish of Cutlashes from the Pyrates, submitted

without a Word, and the Captain came on board; Roberts

saluted him after a friendly Manner, telling him

. . . that their Business with him, was only to be

informed which was the richest Ship in that Fleet;

and if he directed them right, he should be restored

to his Ship without Molestation, otherwise, he must

expect immediate Death. Whereupon this Portuguese

Master pointed to one of 40 Guns, and 150 Men, a

Ship of greater Force than the Rover, but

this no Ways dismayed them . . . so immediately

steered away for him. When they came within Hail,

the Master whom they had Prisoner, was ordered to

ask, how Seignior Captain did? and to invite him on

board . . . But by the Bustle that immediately

followed, the Pyrates perceived they were discovered

. . . so without further Delay, they poured in a

Broadside, boarded and grappled her; the Dispute was

short and warm, wherein many of the Portuguese fell,

and two only of the Pyrates.” (Defoe, 204-205)

Within the hold and cabins of the vessel, Roberts

and his men discovered sugar, skins, tobacco, 90,000

gold Moidores, and jewelry, including “a Cross set

with Diamonds, designed for the King of Portugal.”

(Defoe, 205)

For more information, I recommend these books:

Coote,

Stephen. Drake: The Life and Legend of an

Elizabethan Hero. Thomas Dunne Books, 2003.

Cordingly, David. Under

the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of

Life Among the Pirates. Random House, 1995.

Defoe, Daniel. A

General History of the Pyrates edited by

Manuel Schonhorn. Dover Publications, 1999. (other

editions of this title list the author as Captain

Charles Johnson)

Esquemeling, John.

[Alexandre Exquemelin] The Buccaneers of

America. The Rio Grande Press, 1992.

Konstam, Angus. Buccaneers

1620-1700. Osprey, 2000.

Konstam, Angus. Elizabethan

Sea Dogs. Osprey, 2000.

Konstam, Angus. Pirates

1660-1730. Osprey, 1998.

Lambert, Frank. The

Barbary Wars: American Independence in the

Atlantic World. Hill and Wang, 2005.

Little, Benerson. The

Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and

Techniques, 1630-1730. Potomac Books, 2005.

Pirates: Terror on

the High Seas -- From the Caribbean to the South

China Sea. Turner Publishing, 1996.

Review

Copyright ©2006 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |

Pirates

always interrogated sailors and passengers on seized

vessels. The threat of torture was often enough to

make them talk, but when necessary, pirates tortured

their prisoners. This information needed to be

confirmed whenever possible, for victims would lie

in hopes of saving their lives. Torture also

revealed hidden booty aboard the prize. On 14

September 1723, Princess had almost reached

Barbados when

Pirates

always interrogated sailors and passengers on seized

vessels. The threat of torture was often enough to

make them talk, but when necessary, pirates tortured

their prisoners. This information needed to be

confirmed whenever possible, for victims would lie

in hopes of saving their lives. Torture also

revealed hidden booty aboard the prize. On 14

September 1723, Princess had almost reached

Barbados when

In

1579,

In

1579,  Pirates

didn’t always attack ships, especially the

Pirates

didn’t always attack ships, especially the  Once the lookout

sighted a potential target, the pirates did not

immediately attack. They stalked the prey to

identify the type of ship, whether she rode low or

high in the water (full cargo vs. empty hold), and

to determine the prey’s possible firepower. This

intelligence gathering took several hours to several

days. “To discern the details of armament and crew

of an unknown vessel by naked sight alone – whether,

for example, the crew were many or few, and how many

ports or cannon the vessel might have – it had to be

no more than a few hundred yards away, and even then

many details were obscure. And because most

nations had other nations’ vessels in their naval

and merchant fleets . . . it was not possible to

determine nationality solely from design or general

characteristics.” (Little, 109)

Once the lookout

sighted a potential target, the pirates did not

immediately attack. They stalked the prey to

identify the type of ship, whether she rode low or

high in the water (full cargo vs. empty hold), and

to determine the prey’s possible firepower. This

intelligence gathering took several hours to several

days. “To discern the details of armament and crew

of an unknown vessel by naked sight alone – whether,

for example, the crew were many or few, and how many

ports or cannon the vessel might have – it had to be

no more than a few hundred yards away, and even then

many details were obscure. And because most

nations had other nations’ vessels in their naval

and merchant fleets . . . it was not possible to

determine nationality solely from design or general

characteristics.” (Little, 109)