Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

In Memoriam

Articles & Taverns

One of

Blackbeard’s most threatening moves was his blockade

of Charles Town in 1718. It seemed an unlikely time

for drink to be involved; nevertheless, it was and

it almost resulted in the destruction of the South

Carolinian port.

Governor

Robert Johnson wrote to the Council of Trade

and Plantations:

. . .

about 14 days ago 4 sail of [pirates] appeared

in sight of the Town tooke our pilot boat and

after wards 8 or 9 sail wth. severall of the

best inhabitants of this place on board and then

sent me word if I did not imediately send them a

chest of medicins they would put every prisoner

to death which for there sakes being complied

with after plundering them of all they had were

sent ashore almost naked. (America, June

18. 556.)

What Johnson omitted

from this account was that the messenger who

delivered the ransom demand had been escorted ashore

by two pirates, who promptly disappeared. The

governor and his advisors set about assembling the

medicine chest, but when they were ready to deliver

it, the pirate escorts couldn’t be found. “A general

alarm was given, and a search was made for the

missing pirates. They were finally discovered,

smiling and gloriously drunk.” (Lee, 47) Upon their

arrival in town, they strode about the streets as if

they had nothing to fear. (In truth, no one was

going to accost them while Blackbeard held the

citizenry at bay.) That’s when they met some

drinking buddies of yore, and they immediately

retired to a tavern to hoist a few and bring each

other up to date. What Johnson omitted

from this account was that the messenger who

delivered the ransom demand had been escorted ashore

by two pirates, who promptly disappeared. The

governor and his advisors set about assembling the

medicine chest, but when they were ready to deliver

it, the pirate escorts couldn’t be found. “A general

alarm was given, and a search was made for the

missing pirates. They were finally discovered,

smiling and gloriously drunk.” (Lee, 47) Upon their

arrival in town, they strode about the streets as if

they had nothing to fear. (In truth, no one was

going to accost them while Blackbeard held the

citizenry at bay.) That’s when they met some

drinking buddies of yore, and they immediately

retired to a tavern to hoist a few and bring each

other up to date.

Such overindulgence was to be expected, but the

delay could have resulted in one domino knocking

over another and another and another. And

Blackbeard’s ire would have had devastating effect

on the pirate victims, Charles Town, and the pirate

escorts had the medicine chest failed to arrive.

Cooler heads prevailed this time, but other pirate

captains wrote safeguards into their articles so

that intemperance didn’t result in dire

consequences.

For example, the 23 August 1723 edition of The

Boston News-Letter printed the Articles of

Agreement under which Edward Low and his men sailed.

(This code had been seized after HMS Greyhound captured

Charles

Harris and other pirates who had been sailing

in consort with Low at the time of the attack.

Twenty-six, including Harris, would hang in Newport,

Rhode Island.) One article concerned being soused.

VI. He

that shall be Guilty of Drunkenness in the Time

of an Engagement, shall suffer what Punishment

the Captain and the majority of the Company

shall think fit. (Tryals of Thirty-six, 3:

191)

Francis

Spriggs, another of Low’s cohorts, captured a

man named Richard Hawkins, who wrote of his

captivity for The British Journal in August

1724. One interesting tidbit pertained to the

company’s handling of those who imbibed overmuch.

In the

Morning they enquire who was drunk the last

Night, and whosoever is voted so, must either be

at the Mast-Head four Hours or receive a

Ten-handed Gopty, (or ten Blows in the Britch)

from the whole Watch. I observ’d it generally

fell on one or two particular Men; for were all

to go aloft that were fuddled over Night, there

would be but few left to look out below. They

seldom let the Man at the Mast-Head cool upon

it, but order him to let down a Rope to hawl up

some hot Punch, which is a Liquor every Man

drinks early in the Morning. They live very

merrily all Day; at Meals the Quarter-Master

overlooks the Cook, to see the Provisions

equally distributed to each Mess; whether they

were drunk or sober, I never heard them drink

any other Health than King George’s. (Pirates,

301)

Although Bartholomew

Roberts preferred tea to alcohol, he

understood the chances of swaying his men to his

preferences weren’t high. The first article in his

code of conduct was “Every Man . . . has equal title

to the fresh Provisions, or strong Liquors, at any

Time seized, and use them at Pleasure . . . .”

(Johnson, 169) The fourth article added one

stipulation to those who would drink after eight in

the evening; they could only do so on the weather

deck. Although Bartholomew

Roberts preferred tea to alcohol, he

understood the chances of swaying his men to his

preferences weren’t high. The first article in his

code of conduct was “Every Man . . . has equal title

to the fresh Provisions, or strong Liquors, at any

Time seized, and use them at Pleasure . . . .”

(Johnson, 169) The fourth article added one

stipulation to those who would drink after eight in

the evening; they could only do so on the weather

deck.

Ashore, in havens friendly to roguish clientele, the

pirates frequented taverns. Nearly every colonial

village, town, and city had at least one where

locals and visitors gathered to eat, drink, and

talk. Captain Thomas Walduck wrote the following to

John Searle, his nephew, in 1708.

Upon all

the new settlements the Spaniards make, the

first thing they do is build a church, the first

thing the Dutch do upon a new colony is build

them a fort, but the first thing ye English do,

be it in the most remote part of ye world, or

amongst the most barbarous Indians, is to set up

a tavern or drinking house. (Codfield)

Pietro

Aretino, an Italian satirist who lived from

1492 to 1556, wrote this about drinking

establishments.

He who

has not been at a tavern knows not what a

paradise it is. O holy tavern! O miraculous

tavern! – holy, because no carking cares are

there, nor weariness, nor pain; and miraculous,

because of the spits, which turn themselves

round and round!

Little wonder that

pirates and locals sought respite there.

Taverns,

originally known as ordinaries, were places where

drinks and meals were served. (If you wanted a room,

that required an inn.) Punch-houses served a

particular mixed drink, usually to lower-class

clientele. (Its secondary meaning, brothel, came

later.) Such places allowed locals to catch up on

news and gossip, or entertain themselves with

gambling or playing cards. The proprietors might be

men or women. On the odd chance that a pirate might

expect a letter, these ordinaries sometimes served

as post offices. They were also places where pirate

captains, merchant captains, and military recruiters

sought new blood.

Marcus

Hook in William Penn’s colony of Pennsylvania

welcomed pirates, including Blackbeard. “Marcus Hook

was the first port of call for Philadelphia from its

earliest days, and later would become the farthest

upriver that large ships could safely navigate”

without a pilot familiar with the tides, navigable

waterways, and unseen dangers of the Delaware River.

(Plank) Marcus

Hook in William Penn’s colony of Pennsylvania

welcomed pirates, including Blackbeard. “Marcus Hook

was the first port of call for Philadelphia from its

earliest days, and later would become the farthest

upriver that large ships could safely navigate”

without a pilot familiar with the tides, navigable

waterways, and unseen dangers of the Delaware River.

(Plank)

If tradition be accepted as authority, at the

conclusion of the seventeenth and the first and

second decades of the eighteenth century the pirates

which then infested the Atlantic coast from New

England to Georgia would frequently stop at Marcus

Hook, where they would revel, and when deep in their

cups would indulge in noisy disputation and broils,

until one of the streets in that ancient borough

from that fact was known as Discord Lane, which name

the same thoroughfare has retained for nearly two

centuries. (Ashmead, 457)

Most taverns

in colonial times were simple in design.

The

earliest taverns were mostly independent

structures, yet they could also be located

within or attached to residential houses. The

interiors . . . were designed with different

rooms, the largest room being the taproom with

furnishings such as chairs, desks, the bar, and

a fireplace. (Streczinki, 30)

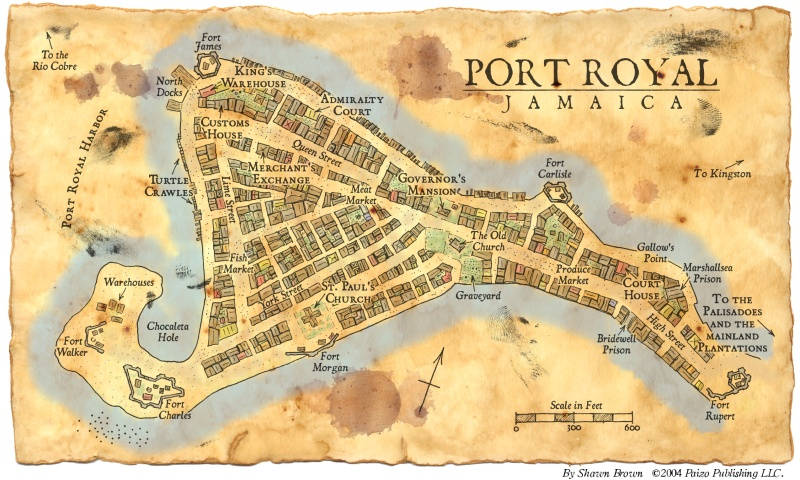

Outside the tavern, a sign

denoted the establishment’s name in both words and

pictures. Extant deeds prior to 1692, identified

nineteen taverns that buccaneers might have visited

in Port Royal,

Jamaica.

Tavern Name

|

Date

|

Location

|

The Three Tunns

|

1665

|

east side of private alley

across from Wherry Bridge

|

The Sugar Loaf

|

1667

|

location unknown

|

The Sign of Bacchus

|

1673

|

Yorke Street

|

The Three Crownes

|

1673

|

corner of High Street and Lime

|

The Green Dragon

|

1674

|

Smith’s Alley and Queen Street

|

The Shipp

|

1674

|

Queen Street

|

The Catt and Fiddle

|

1676

|

Thames Street

|

The Jamaica Arms

|

1677

|

Yorke Street

|

The Three Mariners

|

1677

|

west side of Honey Lane

|

| The Blue Anchor |

1679 |

location unknown |

| The Salutaçon |

1680 |

middle plot between Honey Lane

and the King’s house |

| The Feathers |

1681 |

off Thames street on west side

of private alley |

| The Black Dogg |

1682 |

location unknown |

| The Sign of the George |

1682 |

facing old market place |

| The Cheshire Cheese |

1684 |

New Street |

| The Windmill |

1684 |

Cannon Street |

| The Sign of the Mermaid |

1685 |

across from Wherry Bridge at

end of private alley |

Two taverns bore the name

“The King’s Arms.” The first opened in 1677, and

faced the parade ground. The second opened five

years later.

The Feathers was “newly-built with brick” on the

site of a tavern which had the same name. The

proprietors, Thomas and Ann Mills, ran “a large shop

with a large entry with a large balcony room over

them and another room or bed-chamber and a cellar.”

The yard held “an arbour and house of office, a

cookroom of brick next to it, a large lower room

with a partition, and a billiard-room over that,

with a larger pair of stairs going up to it.”

(Pawson, 114)

When Thomas Freeman purchased The Three Tunns from

Charles Whitfield in December 1695, the tavern had

already been serving patrons for some time. It was

located close to The Feathers.

Captain Charles Penhallow of the Port Royal militia

and a warden in his church, owned The Three

Mariners, which he probably bought from Peter

Bartaboa and John Grandmaison, both of whom were

French. The former’s main occupation was carpentry,

and he built Port Royal’s gallows for £3 in 1666.

Nearby was The Salutaçon, which Randolph Bolton ran

for a long time. Jacob Haynes owned the plot of land

on which William Hanson, the city’s blacksmith,

operated The Green Dragon as a tavern and inn.

John Hay, a victualler and merchant, built The Catt

and Fiddle and ran the tavern with his wife

Susannah. Twenty years later, Hay sold the it to

carpenter Moses Watkins for a sum of £800.

It was common for taverns to have different rooms,

and each of these was known by its own name. One

example came from an unnamed tavern owned by Thomas

Taylor. Upon his death in 1674, an inventory was

made of his property.

In a roome

called the Vinroome

A great

wooden chest, a signe, a stripe carpet and an

old saddle

In the Queen’s Head

An old

planeen [sic] bed, a cedar bedstead and three

old leather trunks, a green rugg, a pillow and

bolster

Two diaper

table-clothes and seaven napkins

In the bar room

Two

punch bowles, two earthen potts and a silver

dram cup

In the Nag’s Head

A

tobacco knife, a copper pott, two spitts, a

table and two formes, a wooden pestle and

morer, two old gunns.

In the sellar

About

20 gallons of Madera at 3s. per gallon

About 18 gallons

of brandy at five shillings and sixpence per

gallon

About a hogshead

of sower clarett

A payr of

carriers and eight pounds of candles

In the Rose

An old

truncke with severall old clothes with a set

of green curtins; a table and two forms

In the King’s Head

Six

joynt stooles, elleavon red leather chaires

A fuzends [sic]

and old chest, fower hamockers

A man servant,

about elleavon months to serve

A brasse kettle

and skillet, a small brasse pan, a frying-pan

and a paire of andirons, a lattin dripping-pan

and an ax

Seventy-five

pounds of pewter, being five dishes, sixteen

plates, two salt-sellers, three basons, one

porringer, one sawcer

Two old

chamber-potts, a pottle pott, two pint potts,

two gill potts, a quart pott and a half-pin

pott (Pawson, 147-148)

Although cash was always

welcome, in the colonies it wasn’t always available.

The primary form of currency on St. Christopher’s

(St. Kitts) when the buccaneers preyed in the

Caribbean was sugar. In September 1678, the island’s

assembly passed four acts, one of which concerned

taverns: “An Act touching tavern keepers and rum

punch house keepers not to trust any person upon

account for above 200 lbs. of sugar before taking a

note (sic) for the same.” (America.

March-Sept. 1678, #645.) This prevented drunken

pirates from running up high tabs, unless they

provided some form of written IOU.

Rowdiness was more the norm when it concerned

pirates with money in their pockets. Jonathan Swift,

the Irish satirist who wrote Gulliver’s Travels

(1726), once wrote that “A tavern is a place where

madness is sold by the bottle.” That might be where

the pirates procured their drink, but it wasn’t

always where they drank. Alexandre Exquemelin’s

master

often used to buy a butt of wine and set it in

the middle of the street with the barrel-head

knocked in, and stand barring the way. Every

passer-by had to drink with him, or he’d have

shot them dead with a gun he kept handy. Once he

bought a cask of butter and threw the stuff at

everyone who came by, bedaubing their clothes or

their head, wherever he could reach.

(Exquemelin, 82)

Roche

Brasiliano had a violent streak, which

drunkenness seemed to accentuate. Roche

Brasiliano had a violent streak, which

drunkenness seemed to accentuate.

He had

no self-control at all, but behaved as if

possessed by a sullen fury. When he was drunk,

he would roam the town like a madman. The first

person he came across, he would chop off his arm

or leg, without anyone daring to intervene, for

he was like a maniac. (Exquemelin, 80)

Exquemelin also mentioned that “tavern-keepers let

them have a good deal of credit,” but he warned his

readers not to trust those in Jamaica. If you racked

up too much debt, the tavern keeper could sell you

to gain back his money. “Even the man . . . who gave

the whore so much money to see her naked, and at

that time had a good 3,000 pieces of eight – three

months later he was sold for his debts, by a man in

whose house he had spent most of his money.”

(Exquemelin, 82)

. . . To be continued

Resources:

“America

and West Indies: March 1678,’ in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 10,1677-1680 edited by W.

Noel Sainsbury and J. W. Fortescue. London, 1896,

220-231 (March-Sept. St. Christopher’s. 645.)

“America

and West Indies: August 1698, 22-25,’ in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 16,1697-1698 edited by J. W.

Fortescue. London, 1905, 399-406 (Aug. 25. 771.).

“America

and West Indies: June 1718,” in Calendar of

State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies:

Volume 30, 1717-1718 edited by Cecil Headlam.

London, 1930, 264-287. (June 18. Charles Towne,

South Carolina. 556.).

Andrade, Tonio.

Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First

Great Victory Over the West. Princeton,

2011.

Antony, Robert J. Like

Froth Floating on the Sea: The World of Pirates

and Seafarers in Late Imperial China.

Institute of East Asian Studies, University of

California Berkley, 2003.

Appleby, John C. Women

and English Piracy 1540-1720: Partners and

Victims of Crime. Boydell, 2013.

Ashmead, Henry Graham.

History

of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. L.

H. Everts & Co., 1884.

Bahadur, Jay. The Pirates of Somalia: Inside

Their Hidden World. Pantheon Books, 2011.

Bialuschewski, Arne. Raiders

and Natives: Cross-cultural Relations in the Age

of Buccaneers. University of Georgia, 2022.

Bold in Her

Breeches: Women Prostitutes Across the Ages

edited by Jo Stanley. Pandora, 1996.

Borvo, Alain. “Discover

Aluette, the Game of the Cow,” Traditional

Tarot (21 July 2021).

Bradley, Peter T. Pirates

on the Coasts of Peru 1598-1701.

Independently published, 2008.

Brooks, Baylus C. Quest

for Blackbeard: The True Story of Edward Thache

and His World. Independently published,

2016.

Brown, Edward. A

Seaman’s Narrative of the Adventures During a

Captivity Among Chinese Pirates, on the Coast

of Cochin-China. Charles Westerton,

1861.

Burg, B. R. “The

Buccaneer Community” in Bandits at Sea: A

Pirates Reader edited by C. R. Pennell. New

York University, 2001, 211-243.

Choundas, George. The Pirate Primer: Mastering

the Language of Swashbucklers and Rogues.

Writer’s Digest, 2007.

Codfield, Rod. “Tavern

Tales: 1708 Letter,” Historic London

Town & Gardens (2 April 2020).

Cotton, Charles. The

Compleat Gamester. London: Charles Brome,

1710.

Croce, Pat. The

Pirate Handbook. Chronicle Books, 2011.

Dampier, William. A New

Voyage Round the World vol. 1. London:

James Knapton, 1699.

Defoe, Daniel. A

General History of the Pyrates edited by

Manuel Schonhorn. Dover, 1999.

Duffus, Kevin P. The

Last Days of Black Beard the Pirate. Looking

Glass Productions, 2008.

Eastman, Tamara J., and Constance Bond. The

Pirate Trial of Anne Bonny and Mary Read.

Fern Canyon Press, 2000.

Ellms, Charles. The

Pirates Own Book. 1837.

Esquemeling, John. The Buccaneers of America.

Rio Grande Press, 1684.

Exquemelin, Alexander

O. The Buccaneers of America translated by

Alexis Brown. Dover, 1969.

“FAQs:

Beverages,” Food Timeline edited by

Lynne Olver (30 November 2021).

Ford, Michael. “The

Attack of the ‘Last Great Pirate’ – Benito De

Soto, Wellington’s Treasure and the Raid of the

‘Morning Star,’ Military History Now

(21 June 2020).

Ford, Michael E. A. Hunting

the Last Great Pirate: Benito de Soto and the

Rape of the Morning Star. Pen & Sword,

2020.

A Full

and Exact Account of the Tryal of the Pyrates

Lately Taken by Captain Ogle. London:

J. Roberts, 1723.

Further

State of the Ladrones on the Coast of China.

Lane, Darling, and Co., 1812.

Geanacopulos, Daphne Palmer. The Pirate Next

Door: The Untold Story of Eighteenth Century

Pirates’ Wives, Families and Communities.

Carolina Academic, 2017.

Gutzlaff, Charles. Three

Voyages Along the Coast of China in 1831,

1832, & 1833. Frederick, Westley

and A. H. Davis, 1834.

Hacke, William. Collection

of Original Voyages. London: James

Knapton, 1699.

Hailwood, Mark. “‘Come

hear this ditty’: Seventeenth-century

Drinking Songs and the Challenges of Hearing the

Past,” The Appendix (10 July 2013).

Hughes, Ben. Apocalypse

1692: Empire, Slavery, and the Great Port Royal

Earthquake. Westholme, 2017.

Jacob, Robert. “Popular

Games from the Golden Age!” Robert Jacob.

Jamaica Rose. “Games

Pirates Played,” Pirates Magazine (Summer

2006), 53-55.

Jamaica Rose. “Pirate

Pastimes & Pleasures,” Pirates Magazine

(Summer 2006), 49-51.

Jameson, John Franklin.

Privateering

and Piracy in the Colonial Period:

Illustrative Documents. Macmillan, 1923.

Johnson, Charles. A General

History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most

Notorious Pyrates. London: C. Rivington,

1724.

Kehoe, M. “Booze,

Sailors, Pirates and Health in the Golden Age of

Piracy,” The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals:

Tools and Procedures.

Kehoe, M. “Christmas

Holidays at Sea in the Golden Age of Piracy,”

The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals: Tools and

Procedures.

Kehoe, Mark C. “Fresh

Water at Sea in the Golden Age of Piracy,” The

Pirate Surgeon’s Journals.

Kehoe, M. “Tobacco

and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy,”

The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals: Tools and

Procedures.

Kelleher, Connie. The

Alliance of Pirates: Ireland and Atlantic Piracy

in the Early Seventeenth Century. Cork

University, 2020.

King

James Bible Online.

Labat, Jean-Baptiste. The

Memoirs of Père Labat, 1693-1705

translated and abridged by John Eaden.

Routledge, 2013.

Lane, Kris E. Pillaging the Empire:

Piracy in the Americas, 1500-1750. M. E.

Sharpe, 1998.

Lee, Robert E. Blackbeard

the Pirate: A Reappraisal of His Life and Times.

John F. Blair, 2002.

“Liar’s

Dice,” Awesome Dice.

Little, Benerson. The

Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish

Main, 1674-1688. Potomac Books, 2007.

Little, Benerson. “Of

Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar

Smoking Women,” Swordplay &

Swashbucklers (1 January 2017).

Little, Benerson. The

Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and

Techniques, 1630-1730. Potomac Books, 2005.

Marley, David F. Pirates of the Americas

Volume 1 1650-1685. ABC Clio, 2010.

Marley, David F. Pirates

of the Americas Volume 2 1686-1725. ABC

Clio, 2010.

McAlister, Zac. “What Is

Black Strap Rum,” Booze Bureau.

Neumman, Charles Fried. History

of the Pirates Who Infested the China Sea,

from 1807 to 1810. Oriental

Translation Fund, 1831.

Parlett, David. “Historic

Card Games,” Games & Gamebooks.

2022.

Pawson, Michael, and

David Buisseret. Port Royal, Jamaica.

University of the West Indies, 2000.

“Pirate

Potheads? On Drugs and Tobacco in the Golden Age

of Piracy,” Gold and Gunpowder (8

December 2023).

The Pirate’s

Pocket-Book edited by Stuart Roberston.

Conway, 2008.

Pirates in Their Own

Words: Eye-witness Accounts of the ‘Golden Age’

of Piracy, 1690-1728 edited by E. T. Fox.

Fox Historical, 2014.

“The Plank

House,” The Marcus Hook Preservation

Society.

Preston, Diana and

Michael. A Pirate of Exquisite Mind: Explorer,

Naturalist, and Buccaneer: The Life of William

Dampier. Walker & Co., 2004.

Pruitt, Sarah. “How

Christmas Was Celebrated in the 13 Colonies,”

History (5 October 2023).

Rogers, Woodes. A

Cruising Voyage Round the World.

Cassell and Company, 1928.

Sanders, Richard. If a Pirate I must be . . .

: The True Story of “Black Bart,” King of the

Caribbean Pirates. Skyhorse, 2007.

Sanna, Antonio.

“Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum”: Representations of

Drunkenness in Literary and Cinematic Narratives

on Pirates,” Pirates in History and Popular

Culture edited by Antonio Sanna. McFarland,

2018, 120-131.

Schenawolf, Harry. “Music in

Colonial America,” Revolutionary War

Journal (21 August 2014).

Sharp, Bartholomew. Voyages

and Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp. P. A.

Esq., 1684.

Snelders, Stephen. “Smoke on

the Water: Tobacco, Pirates, and Seafaring

in the Early Modern World,” Intoxicating

Spaces: The Impact of New Intoxicants on Urban

Spaces in Europe, 1600-1850 (9 December

2019).

Snelgrave, William. A

New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, and the

Slave Trade. London: James, John, and Paul

Knapton, 1734.

Struzinski, Steven. “The

Tavern in Colonial America,” The

Gettysburg Historical Journal volume 1,

article 7 (2002), 29-38.

Sutton, Angela C. Pirates

of the Slave Trade: The Battle of Cape Lopez and

the Birth of an American Institution.

Prometheus, 2023.

Talty, Stephan. Empire of Blue Water: Captain

Morgan’s Great Pirate Army, the Epic Battle for

the Americas, and the Catastrophe That Ended the

Outlaws’ Bloody Reign. Crown, 2007.

Thomson, Keith. Born

To Be Hanged: The Epic Story of the Gentlemen

Pirates Who Raided the South Seas, Rescued a

Princess, and Stole a Fortune. Little,

Brown, 2022.

Todd. “Daily

Life of the American Colonies: The Role of

the Tavern in Society,” The Witchery Arts

(3 April 2015).

Todd, Janet. “Carleton,

Mary (1634x42-1673),” Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography. Oxford University, 2004.

The

Tryals of Captain John Rackham, and Other

Pirates. Jamaica: Robert Baldwin,

1721.

The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other

Pirates. London: Benj. Cowse, 1719.

“Tryals of Thirty-six

Persons for Piracy” in British Piracy in the

Golden Age: History and Interpretation,

1660-1730 edited by Joel H. Baer. Pickering

& Chatto, 2007, 3:167-192.

Turner, John. Sufferings

of John Turner, Chief Mate of the Country

Ship, Tay. Thomas Tegg, 1810.

Vallar, Cindy. “Pirates

and Music,” Pirates and Privateers

(18 September 2013).

Watson, John F. Annals

of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden

Time, vol. 2. John Penington and Uriah

Hunt, 1844.

Wafer, Lionel. A New

Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of

America. London: James Knapton, 1699.

Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U.,

and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard’s

Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen

Anne’s Revenge. University of North Carolina,

2018.

Winstead, Dave. “1/24/2024

Is ‘Eat, Drink, And Be Merry’ A Biblical

Concept?” FaithByTheWord (24 January

2024).

Yates, Donald. “Colonial

Drinks, 1640-1860,” Bottles and Extras

(Summer 2003), 39-41.

While I worked on

this article, my father passed away.

He shared his affinity for the water

and boats with me in my youth, which

helped awaken a desire to write about

pirates. This article is for him. Now

that you are at peace and without

pain, Dad, may you eat, drink, and be

merry.

Lee Aker

Rest in peace |

Copyright ©2024 Cindy

Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |